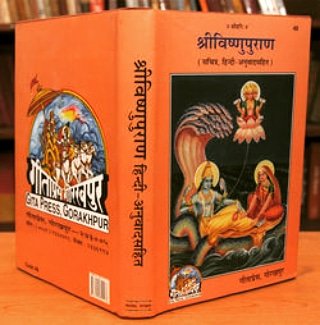

THE STRUCTURE, IMPORTANCE AND ADVANTAGES OF VISHNU PURAN.

Vishnu puran has twenty three thousand shlokas. It has the power to destroy all your sins. In its first part it contains the dialogue between Parashar rishi and Maitrey rishi.

The main topics discussed here are Aadikaraan sarg, origin of devtas, Samudra manthan, the vansh of Daksh, stories of Dhruv and Pruthu, Prachetas analysis, Prahlads story, the distribution of different powers to the various sections of society.

The second part consists of description of Priyavrat vansh, description of Dweeps, Varsh, Swarg, Narak, description of various planet movements, Bharat charitra, Muktimarg and dialogue between Nidhag and Ribhu.

Next is the description of Manvantars, avtaar of Vedvyas,

and ways to get freedom from Narak. Then we find a dialogue between Sagar & Aurva rishi, structure of Dharma, Shradh Kalp,Varnashram dharma, good behavior and story of Maya & Moha.

In the 4th part we find the description of Chandra vansh along with the description of its rulers.

Next are the questions regarding Krishnavtar, Gokul, the slaying of Putna, atrocities of demon Aghasur, Killing of Kansa, leela in Mathura, demons slayed by Krishna in order to ease the load of Prithvi, Krisha's marriages and sermon by Ashtavakra.