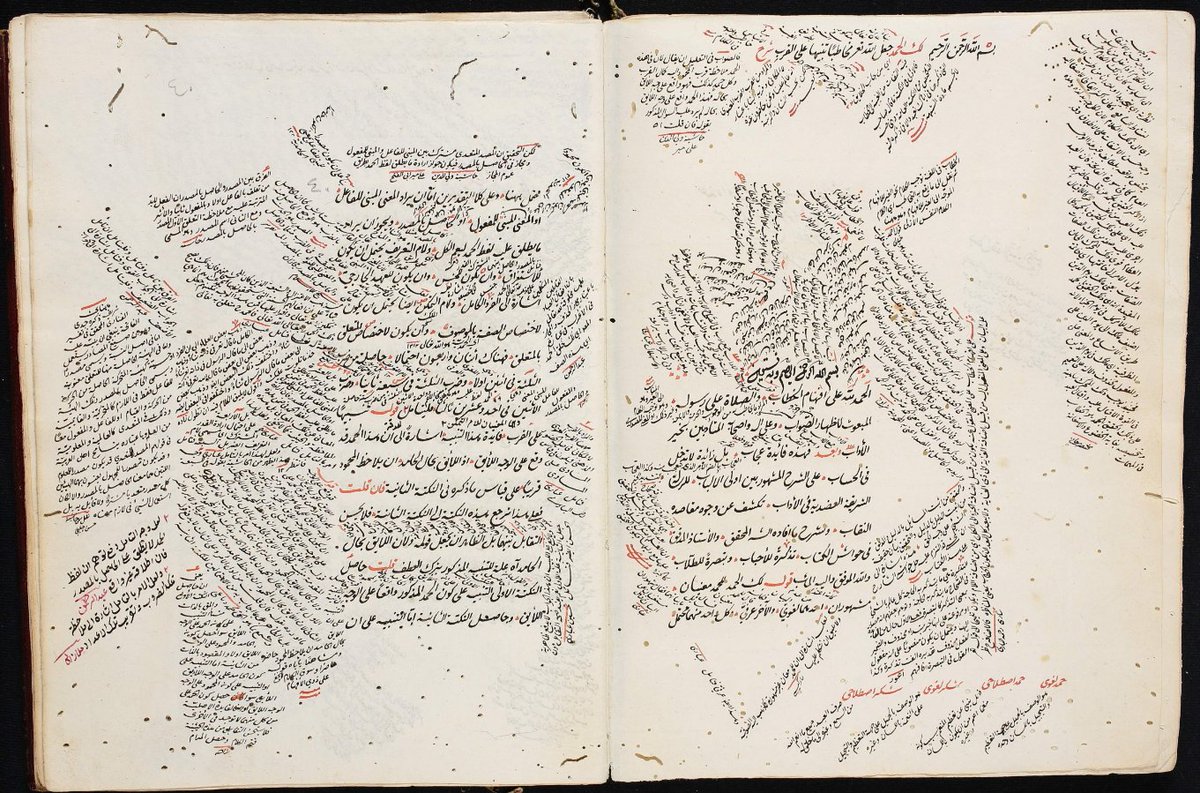

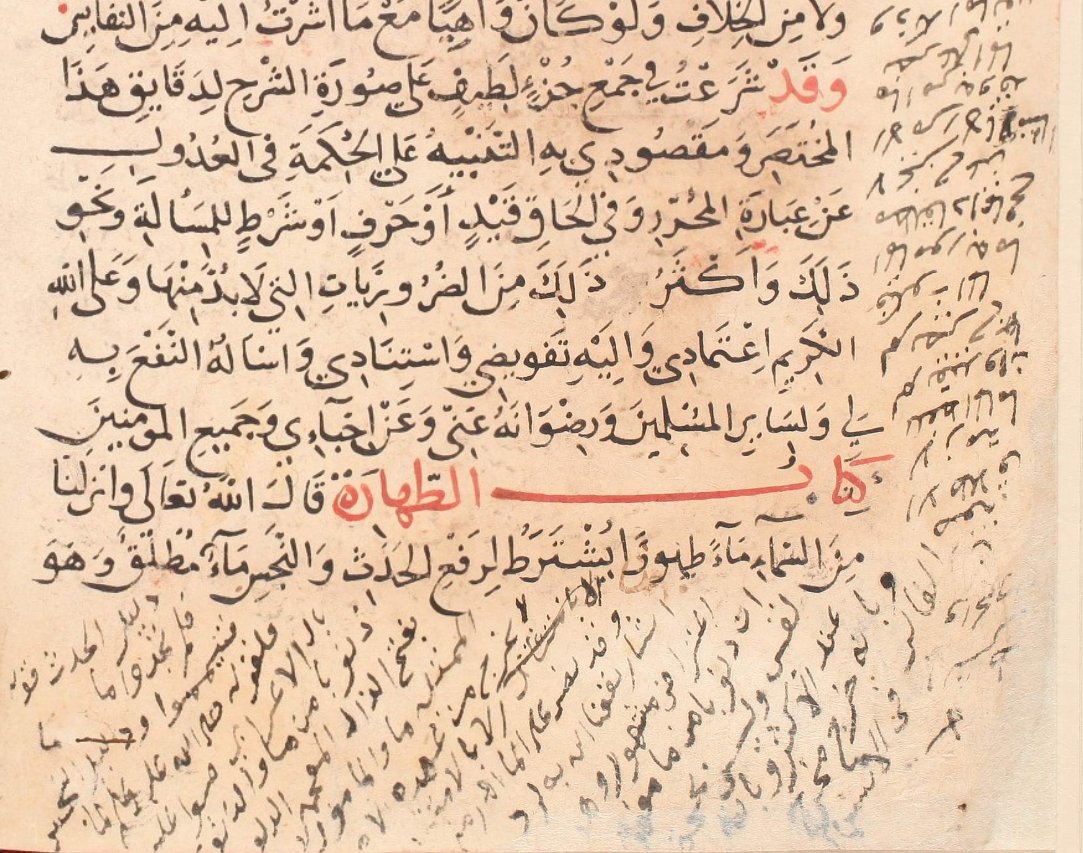

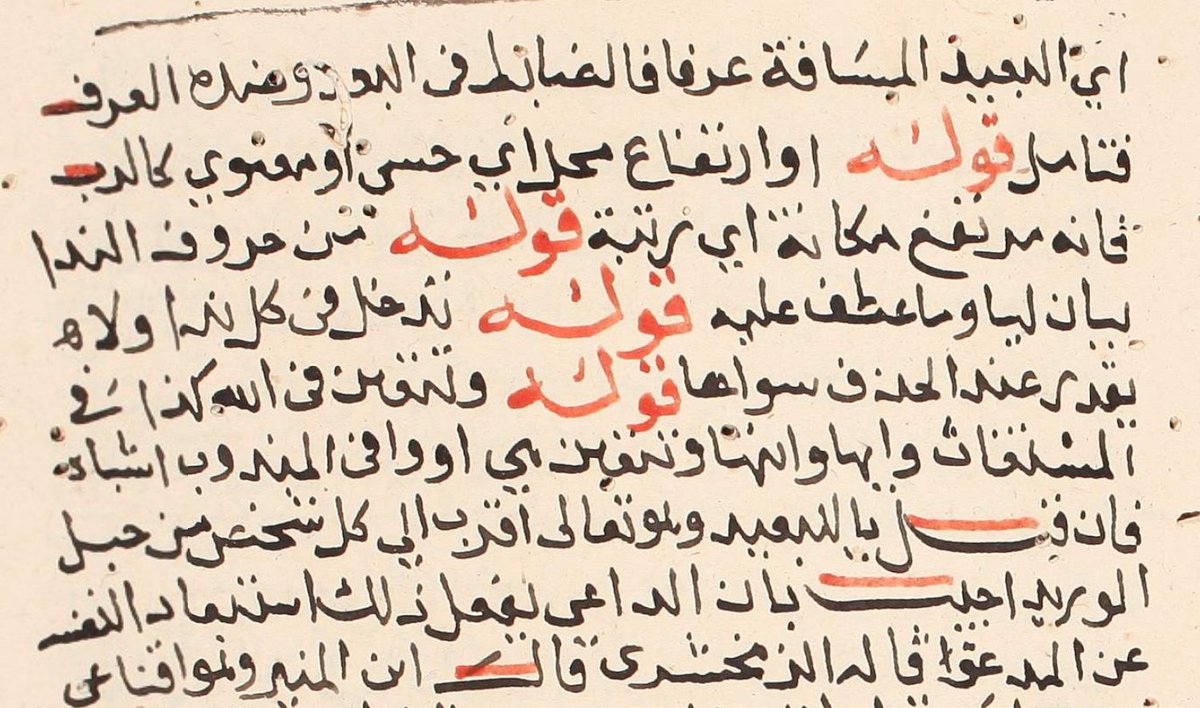

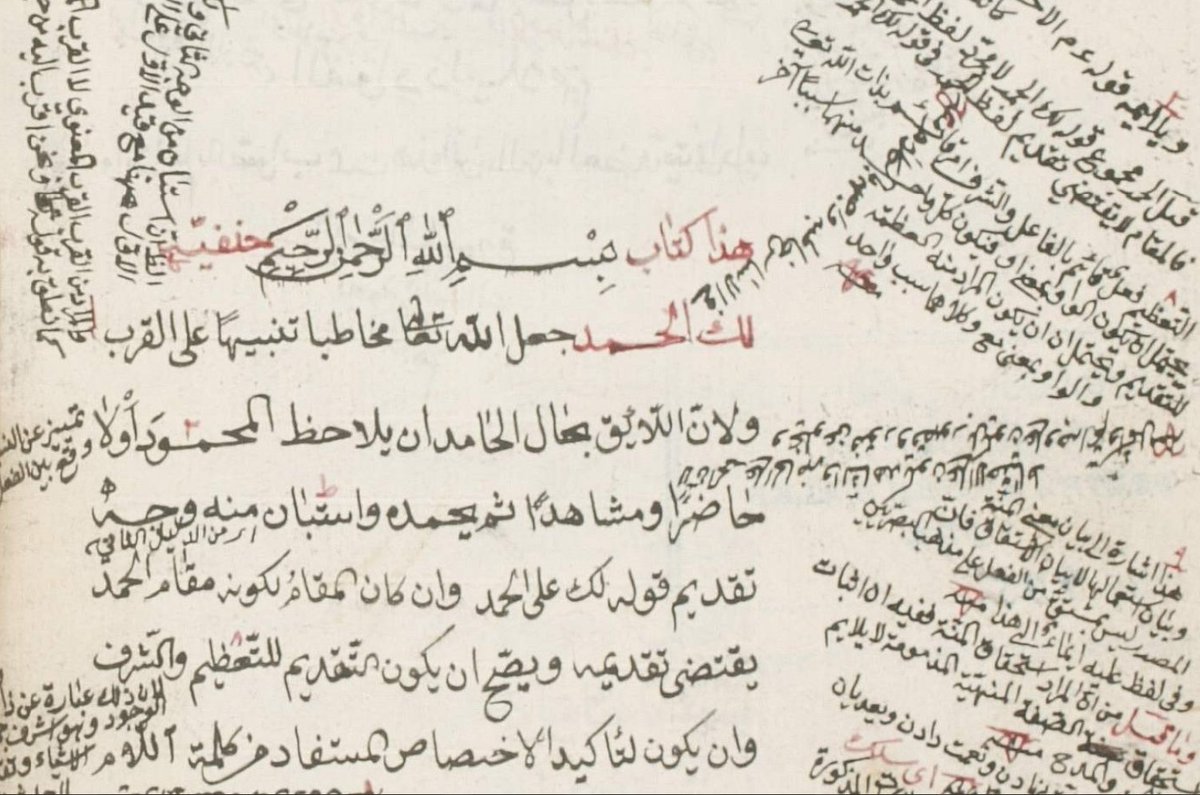

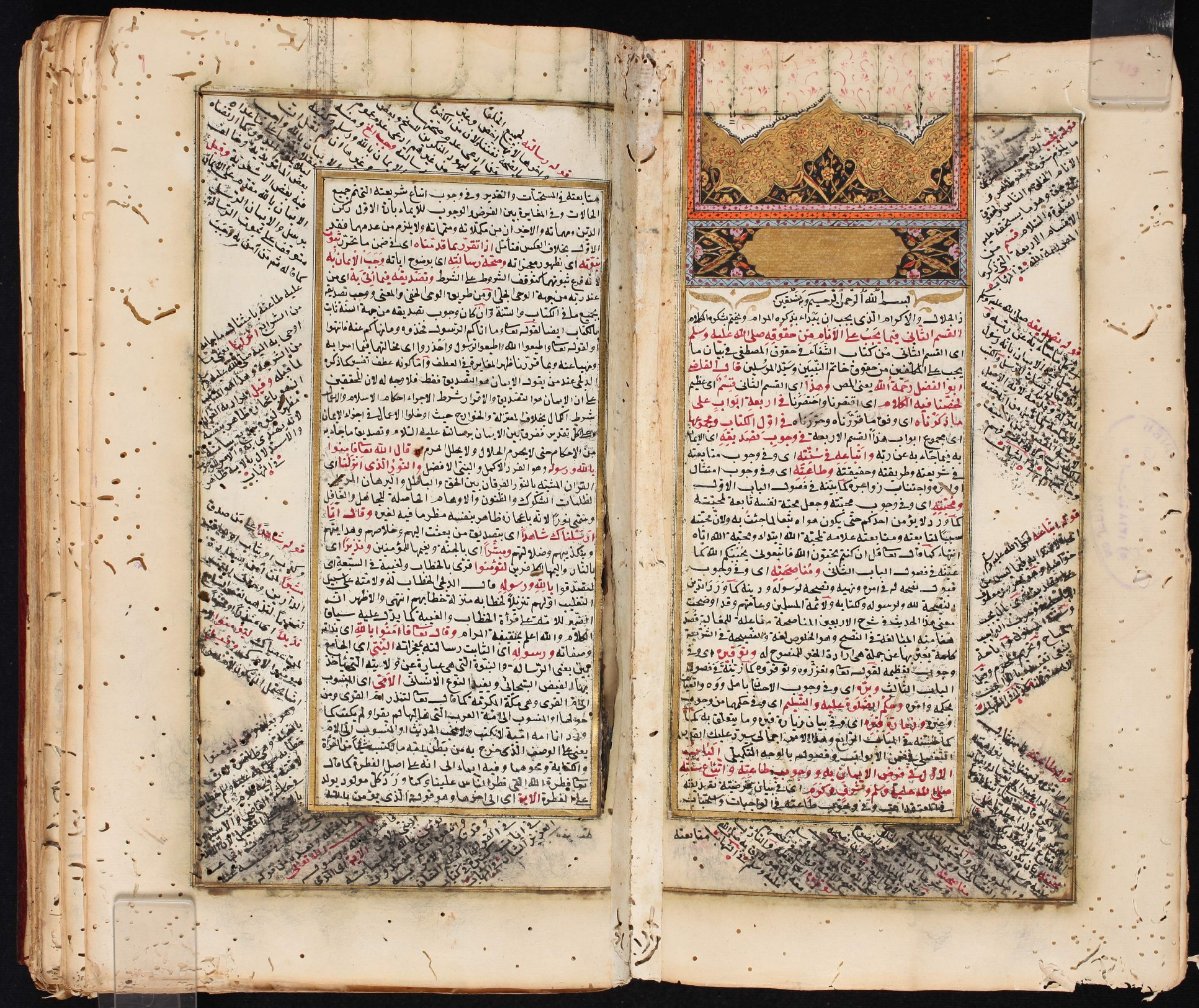

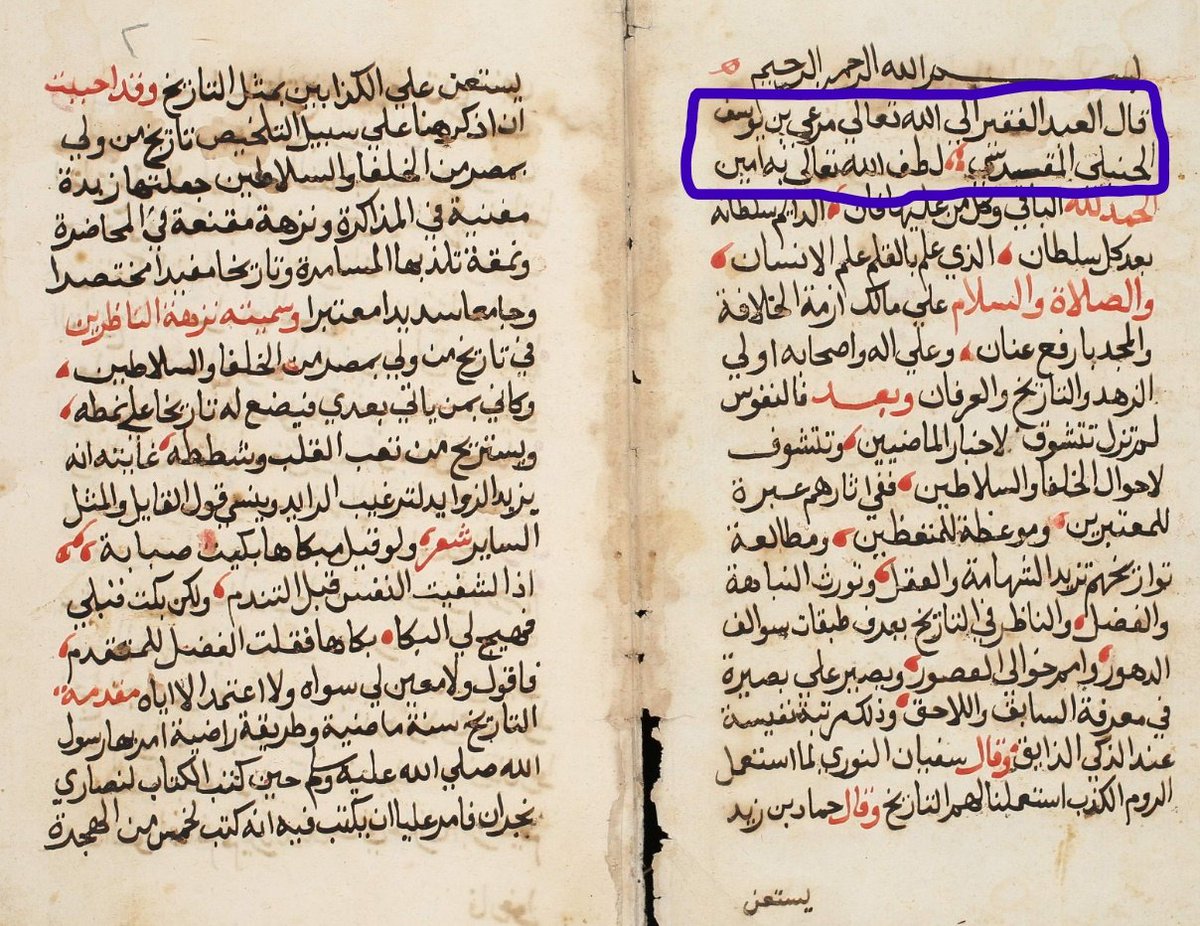

One key element of the Islamic intellectual tradition is the commentary. Commentaries on the Qurʼan (tafsīr) began early in Islamic history, but from about the 12th or 13th century, well into the 19th, commentaries on other scholarly texts became extremely common. -jm

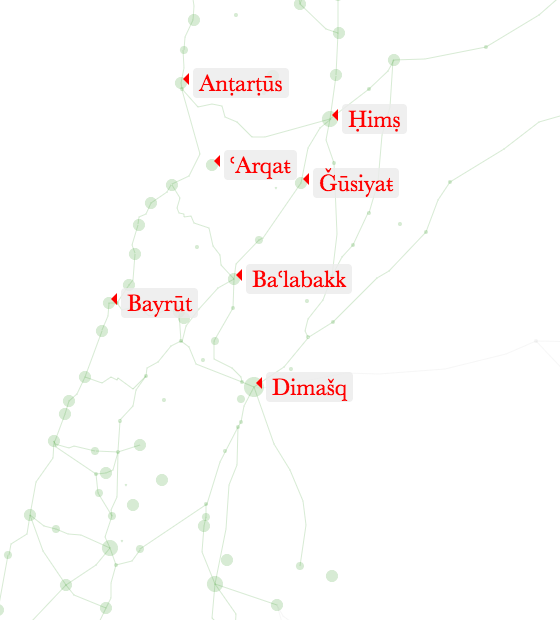

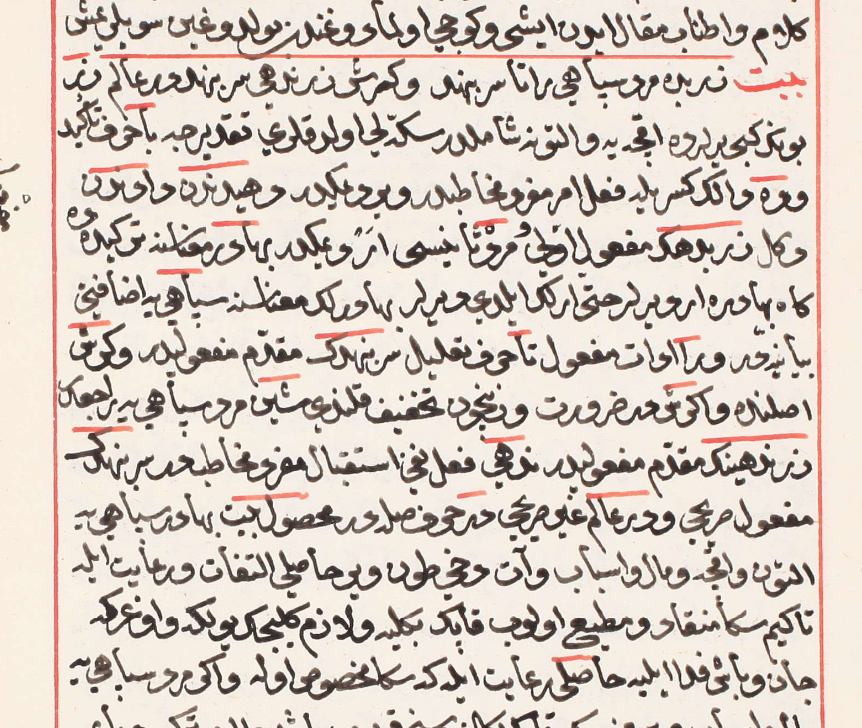

This structure is fairly consistent on texts and manuscripts that come later, once the basic elements of the scholarly tradition have reached some level of stability. But there are some early manuscripts that look quite different, and are much more dynamic. -jm https://t.co/Lr56FJ94U1

— Tweeting Historians (@Tweetistorian) January 13, 2021

More from Tweeting Historians

Budeiry Library (Jerusalem) MS 593 -jm

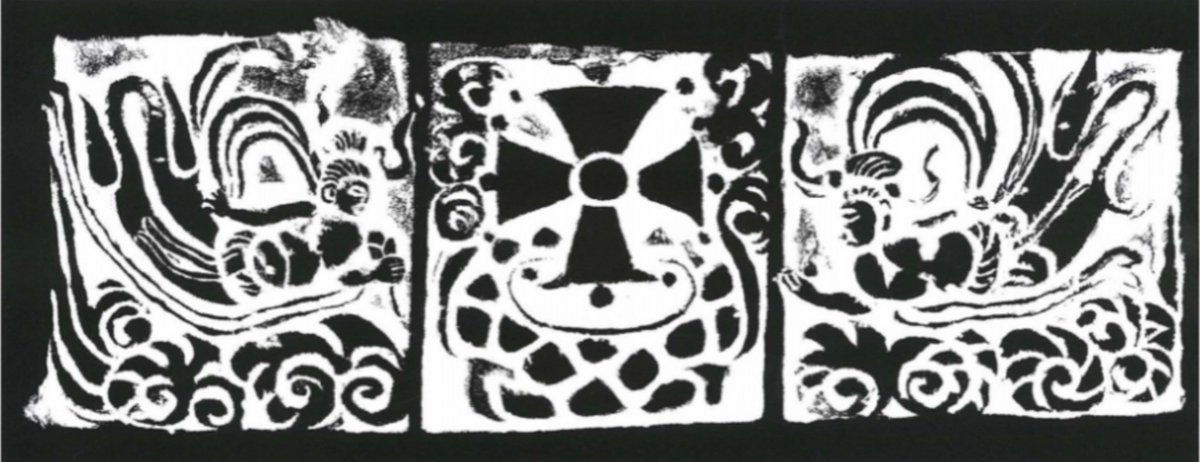

These texts have many elements designed to help the reader understand what they're saying, and choices by the scribe who copied the manuscript often help as well. Let's see what's here. -jm

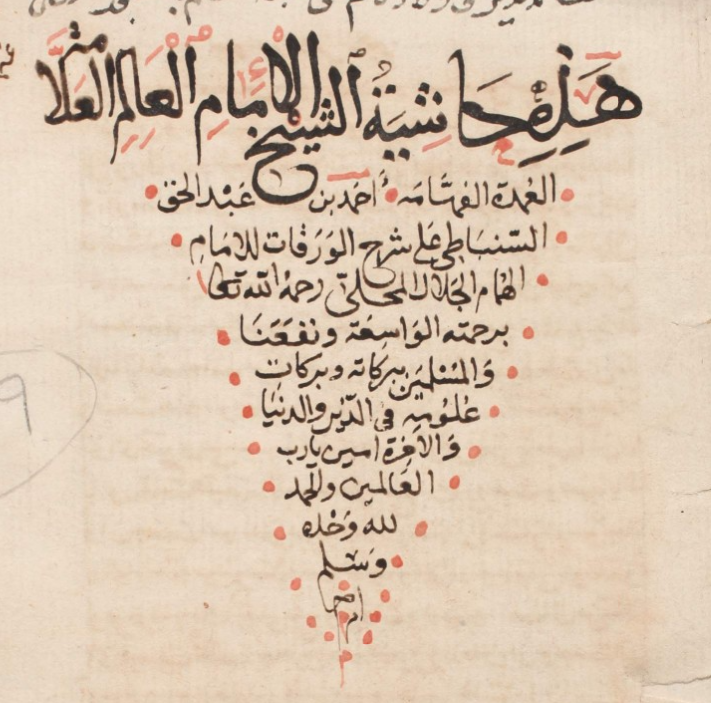

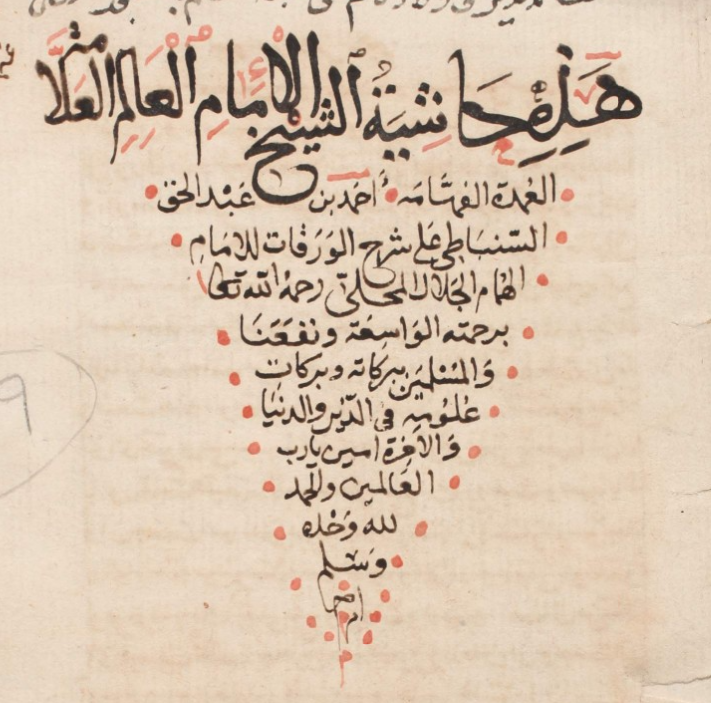

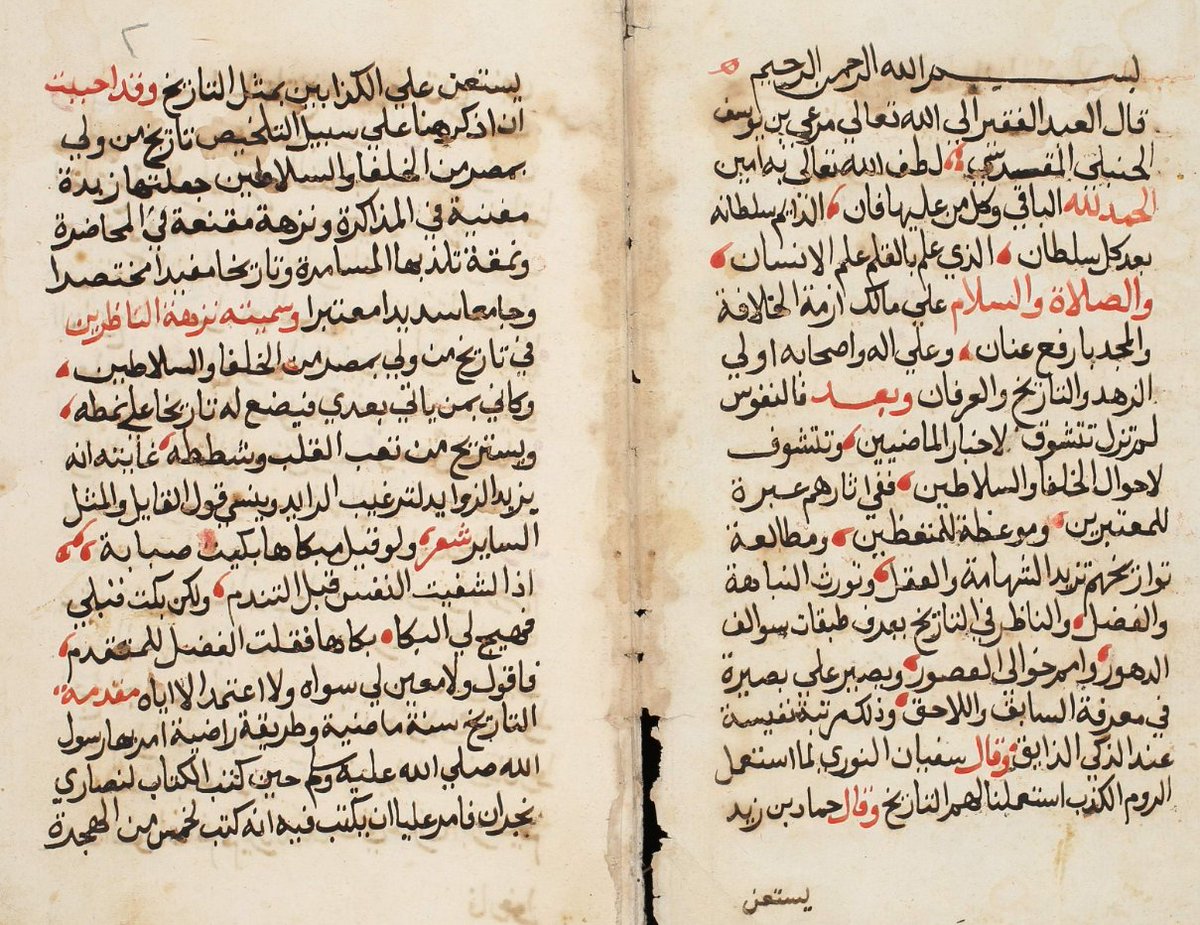

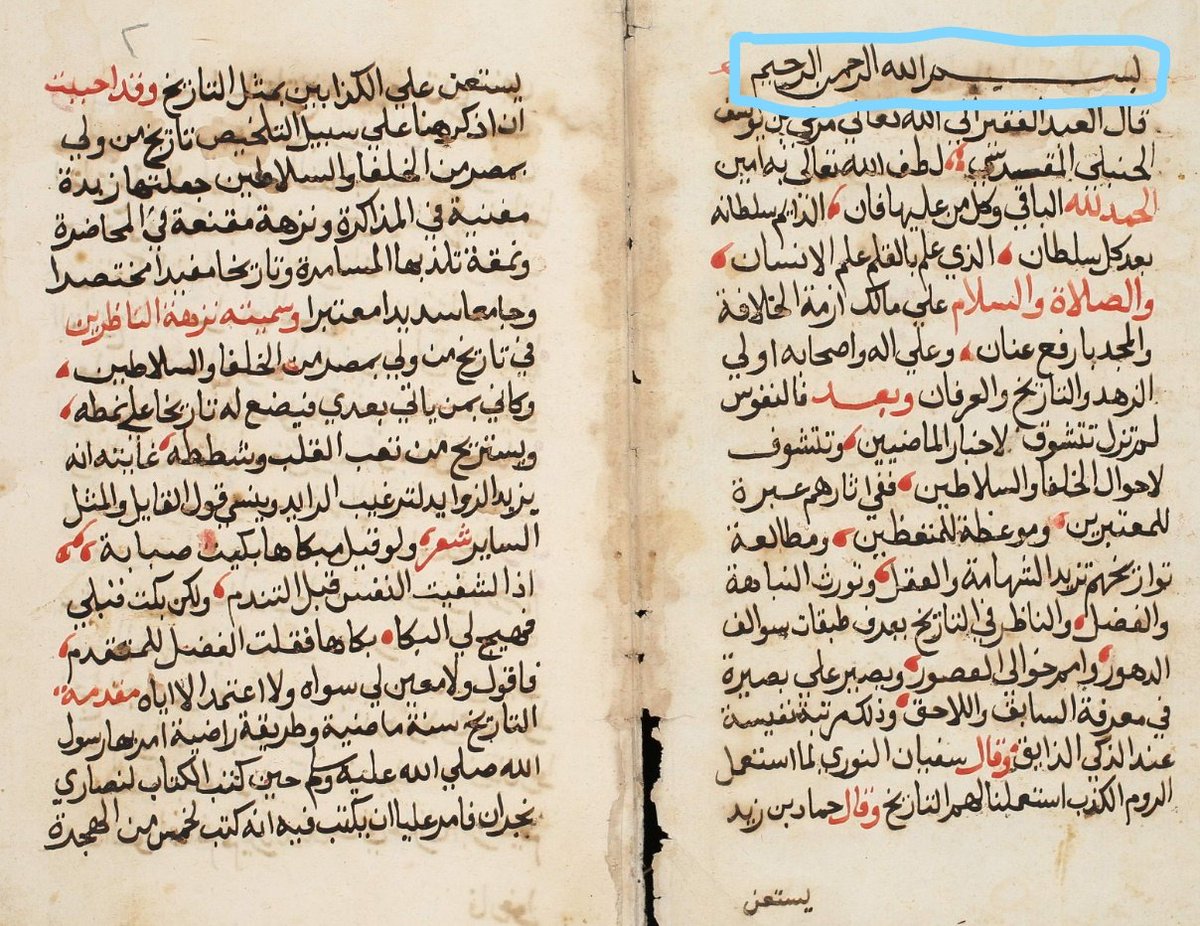

First, almost every Islamic text begins with the invocation "in the name of God, the compassionate, the merciful." The wording is never changed, and it's always in Arabic, no matter what language the text is, although you might add phrases like "and we ask God for help." -jm

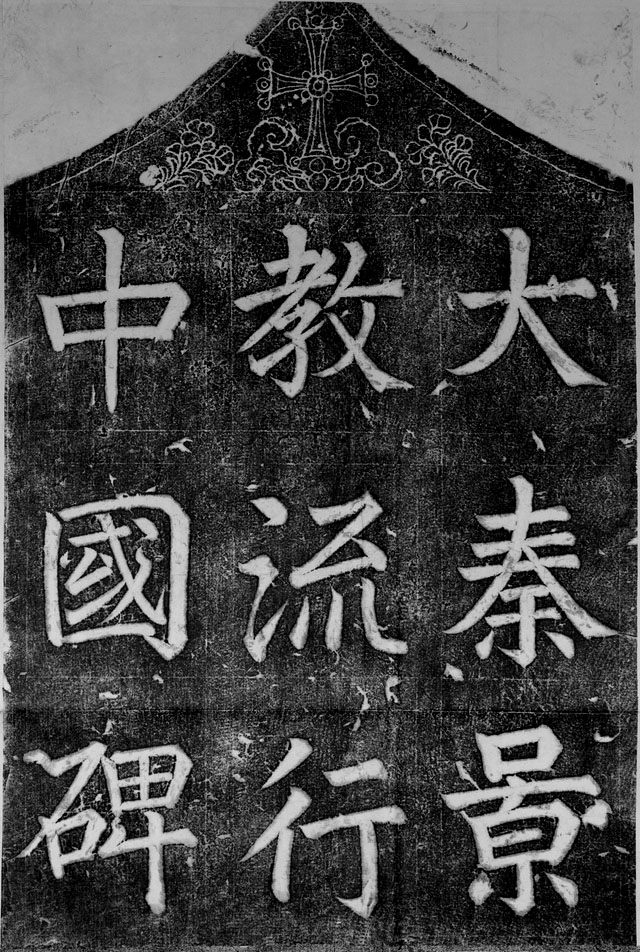

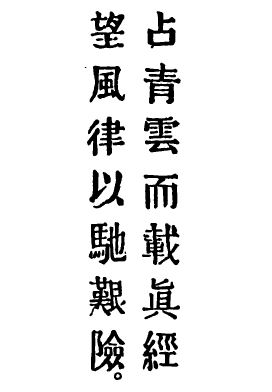

Christians were able to do more experimentation with their invocations, as you can see from the examples here. https://t.co/wEPWRitCWA -jm

These little prayers are fun pic.twitter.com/hJYk2M01bO

— Josh Mugler (@J_mugs) February 16, 2019

After the invocation (basmalah), you might have what this text has, which is an introduction of the author in the form "the poor slave of God [so-and-so] said..." often followed by a quick prayer for the author. -jm

More from Religion

Many RW Hindus with confused identity think that Hinduism accepts Atheists.

What do some of the Hindu sacred texts say on this topic? Let's see.

Shri Krishna was 100% clear on importance of Shaastras as we already know.

Shri Rama was also clear on what should be done to atheists.

Ayodhya Kanda of Valmiki Ramayana.

https://t.co/lbCkEkPobA

Maharaaj Manu on Atheists.

Bhagvan Ved Vyas Ji in Shanti Parva of Mahabharata said this to his son Shukadeva regarding Atheists.

You May Also Like

The story doesn\u2019t say you were told not to... it says you did so without approval and they tried to obfuscate what you found. Is that true?

— Sarah Frier (@sarahfrier) November 15, 2018

In the spring and summer of 2016, as reported by the Times, activity we traced to GRU was reported to the FBI. This was the standard model of interaction companies used for nation-state attacks against likely US targeted.

In the Spring of 2017, after a deep dive into the Fake News phenomena, the security team wanted to publish an update that covered what we had learned. At this point, we didn’t have any advertising content or the big IRA cluster, but we did know about the GRU model.

This report when through dozens of edits as different equities were represented. I did not have any meetings with Sheryl on the paper, but I can’t speak to whether she was in the loop with my higher-ups.

In the end, the difficult question of attribution was settled by us pointing to the DNI report instead of saying Russia or GRU directly. In my pre-briefs with members of Congress, I made it clear that we believed this action was GRU.

As a dean of a major academic institution, I could not have said this. But I will now. Requiring such statements in applications for appointments and promotions is an affront to academic freedom, and diminishes the true value of diversity, equity of inclusion by trivializing it. https://t.co/NfcI5VLODi

— Jeffrey Flier (@jflier) November 10, 2018

We know that elite institutions like the one Flier was in (partial) charge of rely on irrelevant status markers like private school education, whiteness, legacy, and ability to charm an old white guy at an interview.

Harvard's discriminatory policies are becoming increasingly well known, across the political spectrum (see, e.g., the recent lawsuit on discrimination against East Asian applications.)

It's refreshing to hear a senior administrator admits to personally opposing policies that attempt to remedy these basic flaws. These are flaws that harm his institution's ability to do cutting-edge research and to serve the public.

Harvard is being eclipsed by institutions that have different ideas about how to run a 21st Century institution. Stanford, for one; the UC system; the "public Ivys".

Independent and 100% owned by Joe, no networks, no middle men and a 100M+ people audience.

👏

https://t.co/RywAiBxA3s

Joe is the #1 / #2 podcast (depends per week) of all podcasts

120 million plays per month source https://t.co/k7L1LfDdcM

https://t.co/aGcYnVDpMu