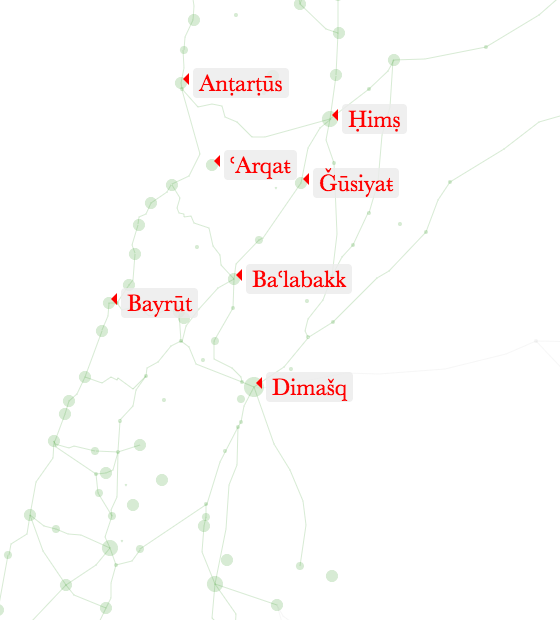

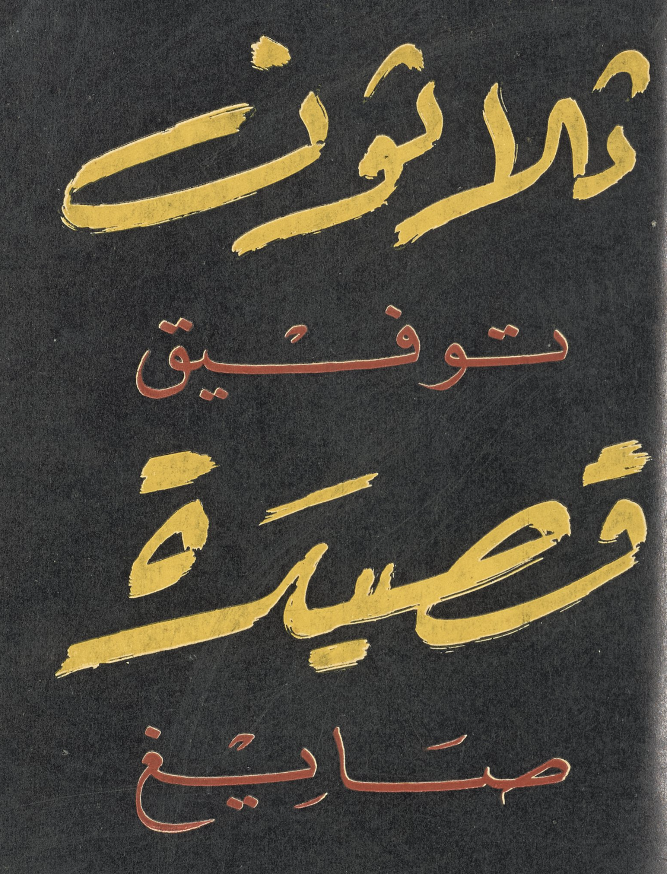

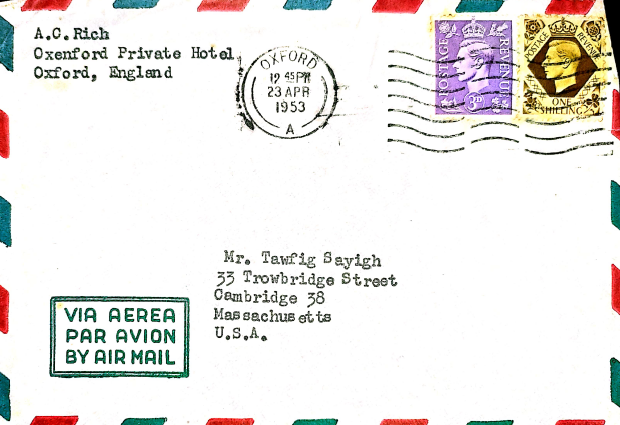

1/25 Today, I will continue looking at the lives of Palestinian poets in the context of the intellectual battle over modernizing Arabic poetry after 1948. A marginalized and maligned figure in Arab intellectual history in the Cold War is Tawfiq Sayigh (1923-71) ~AA.

More from Tweeting Historians

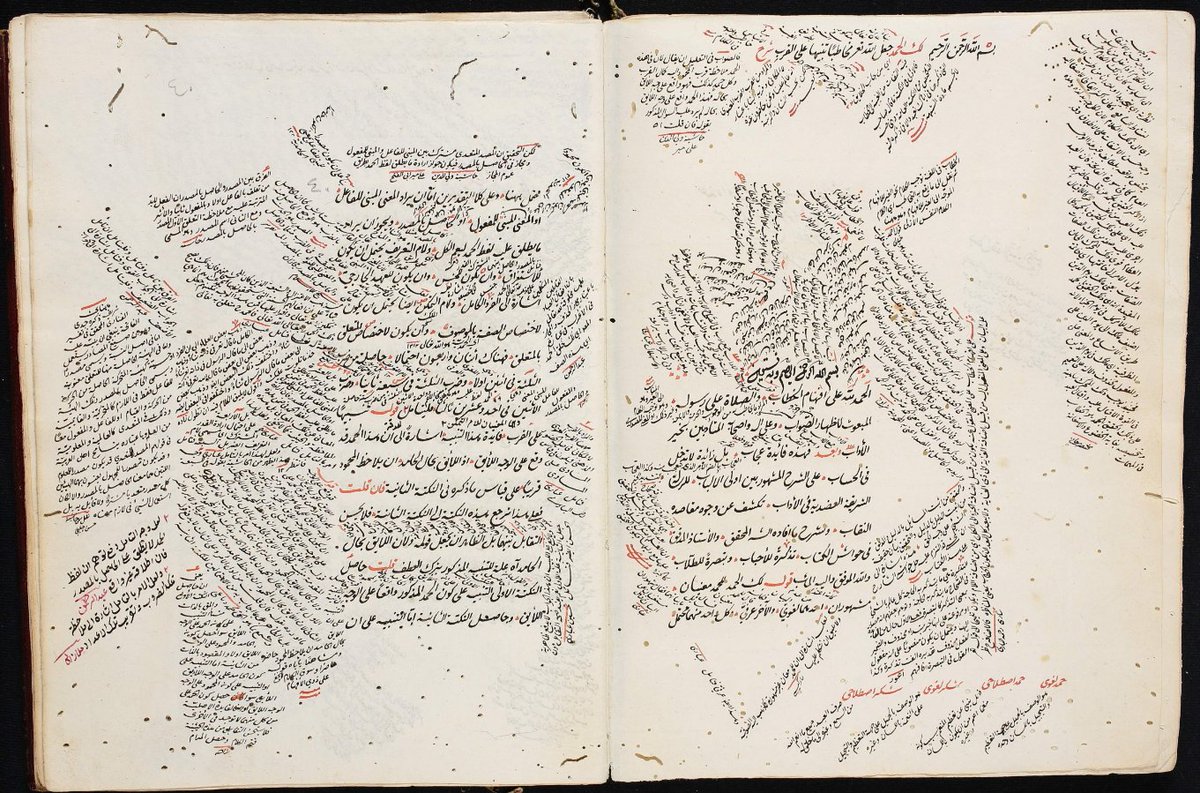

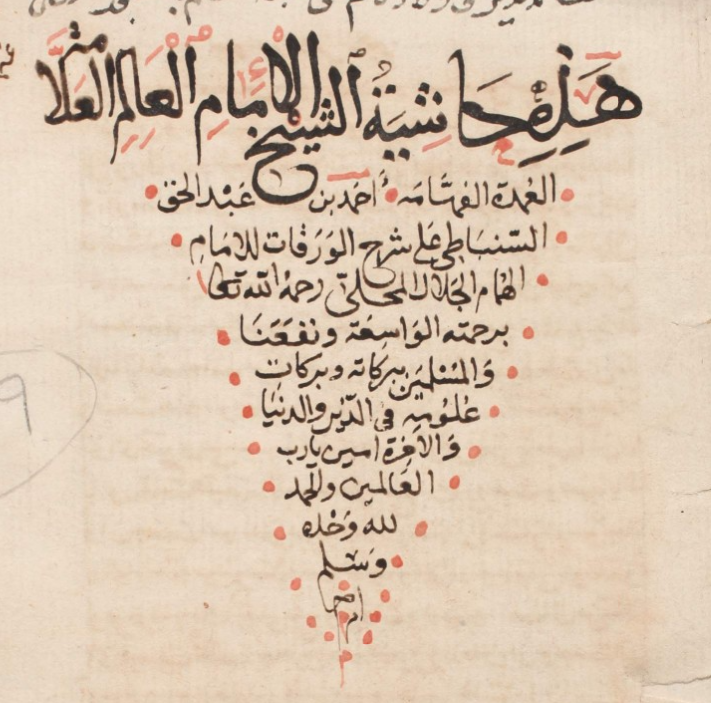

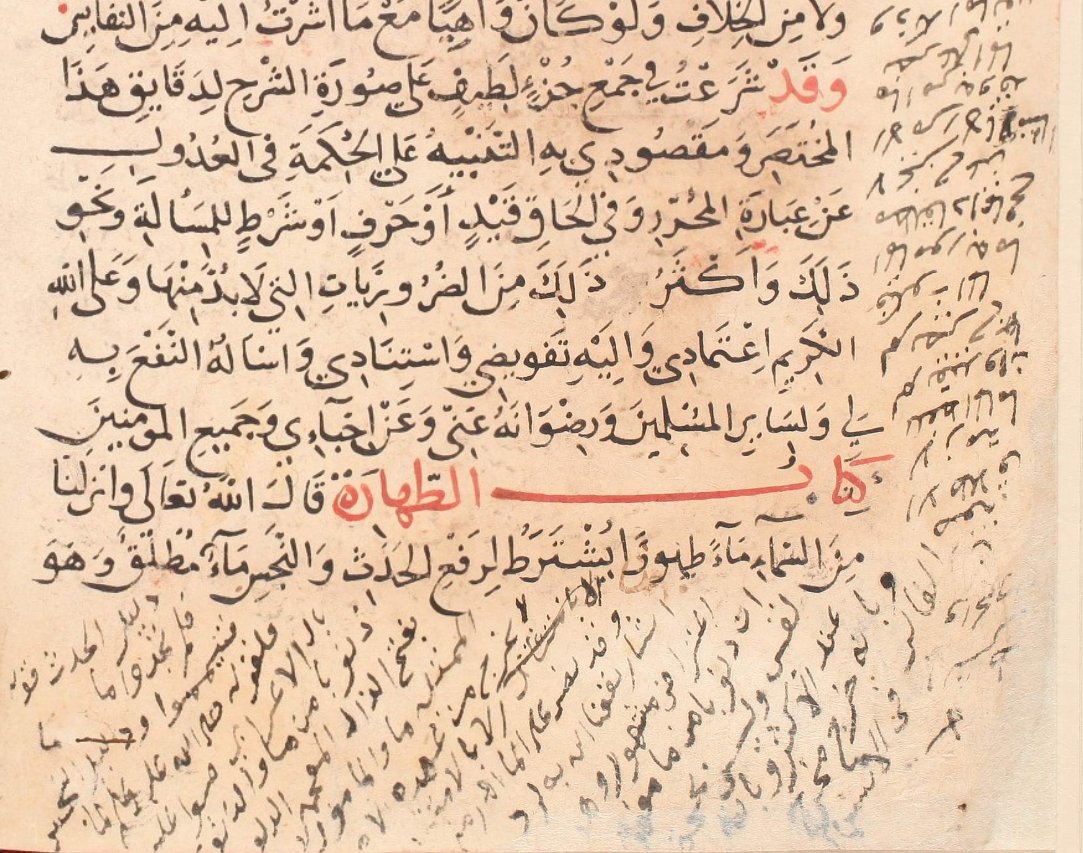

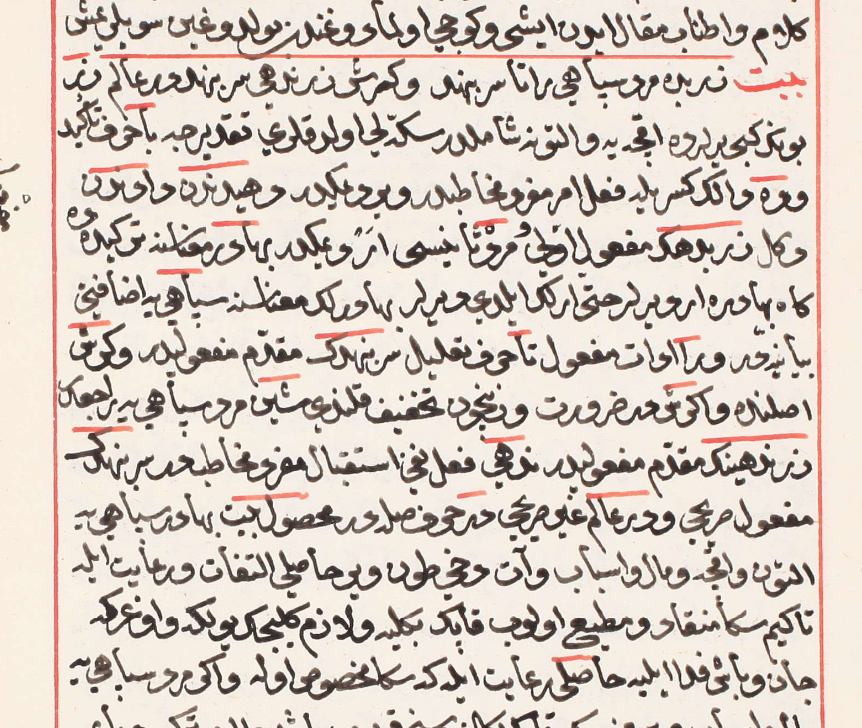

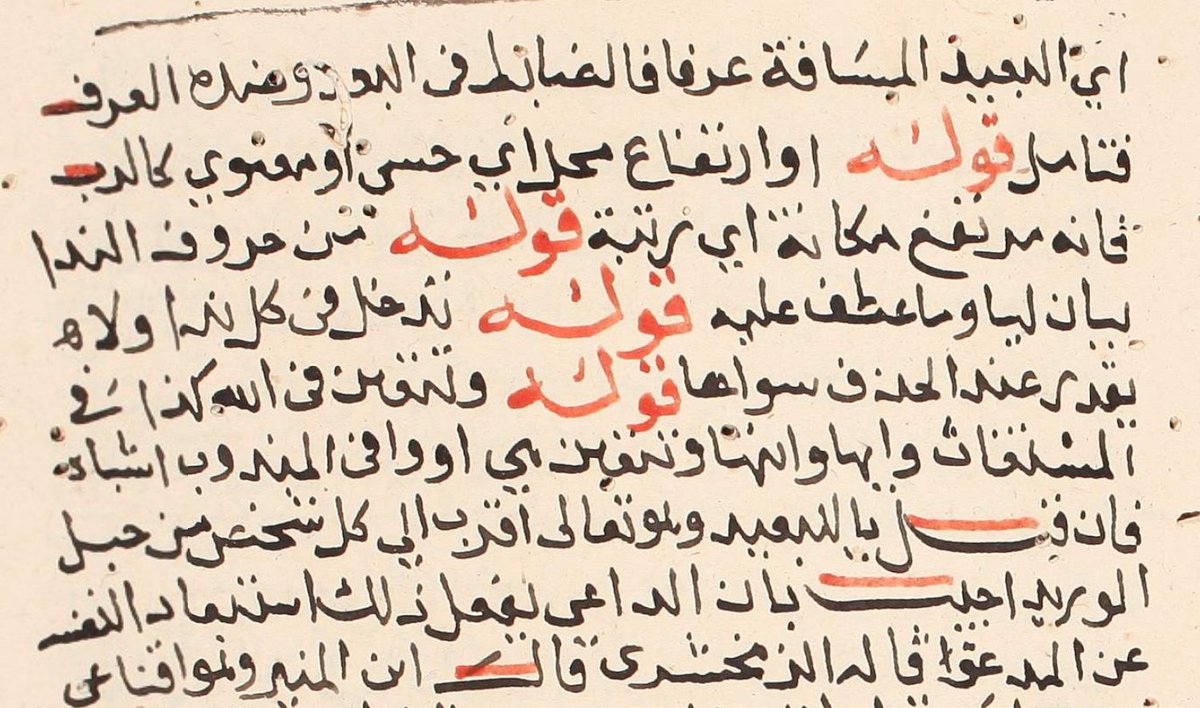

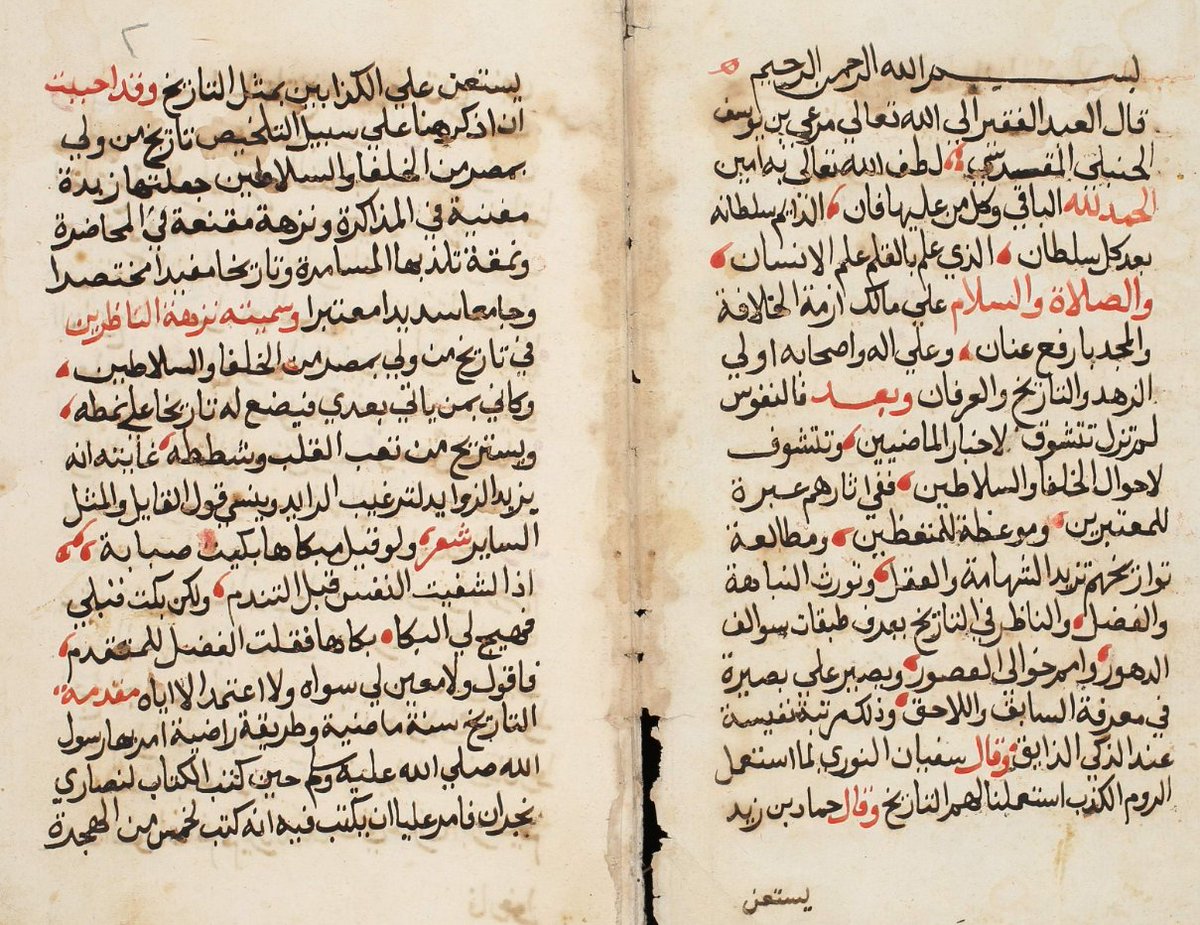

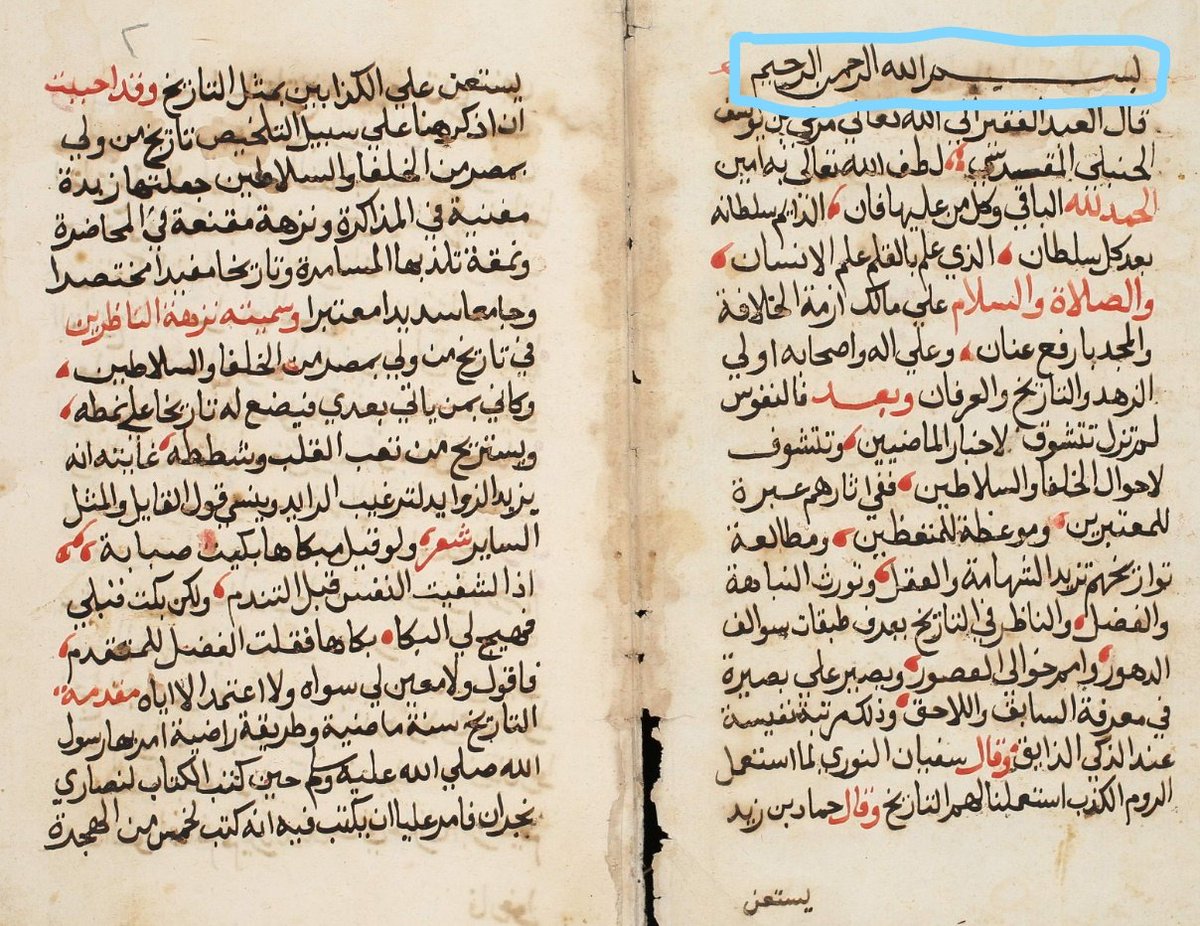

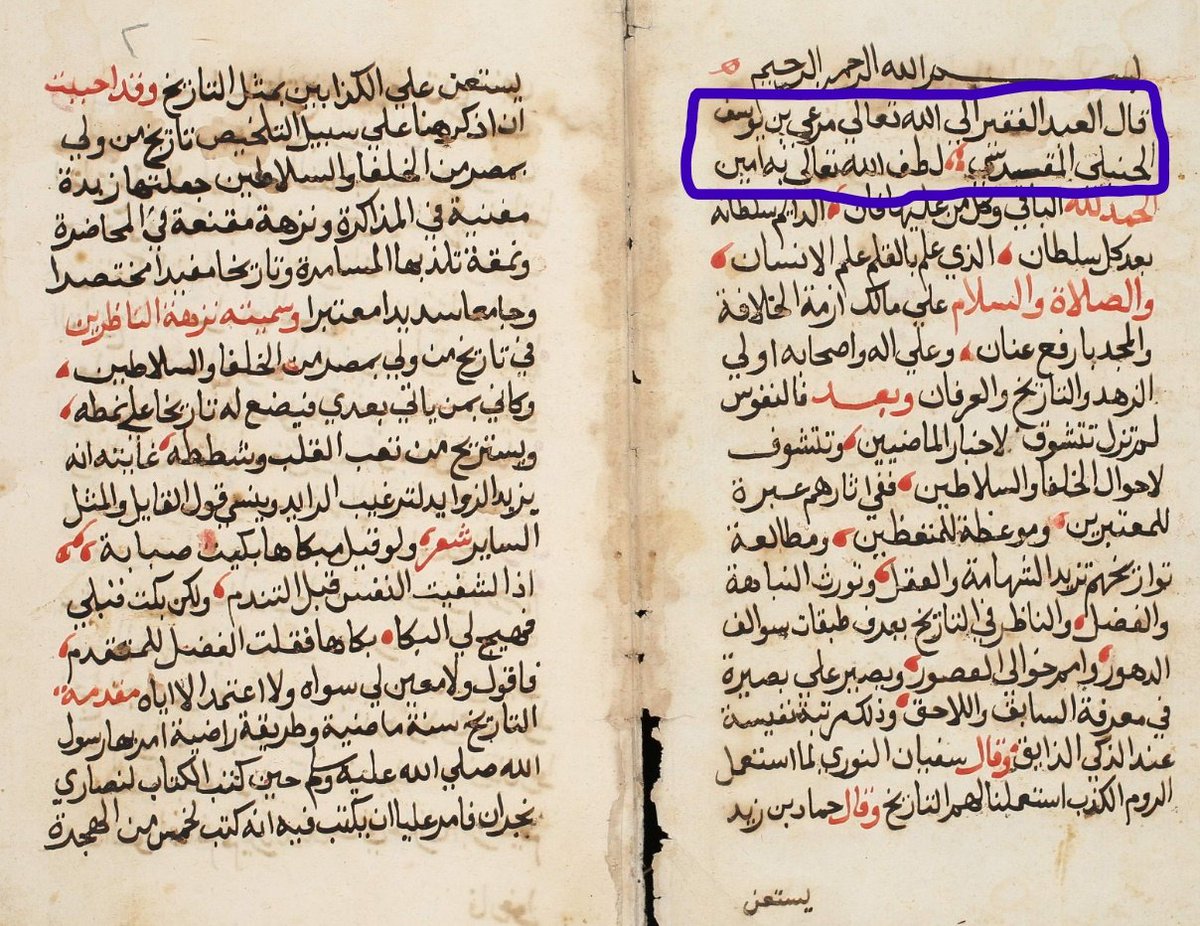

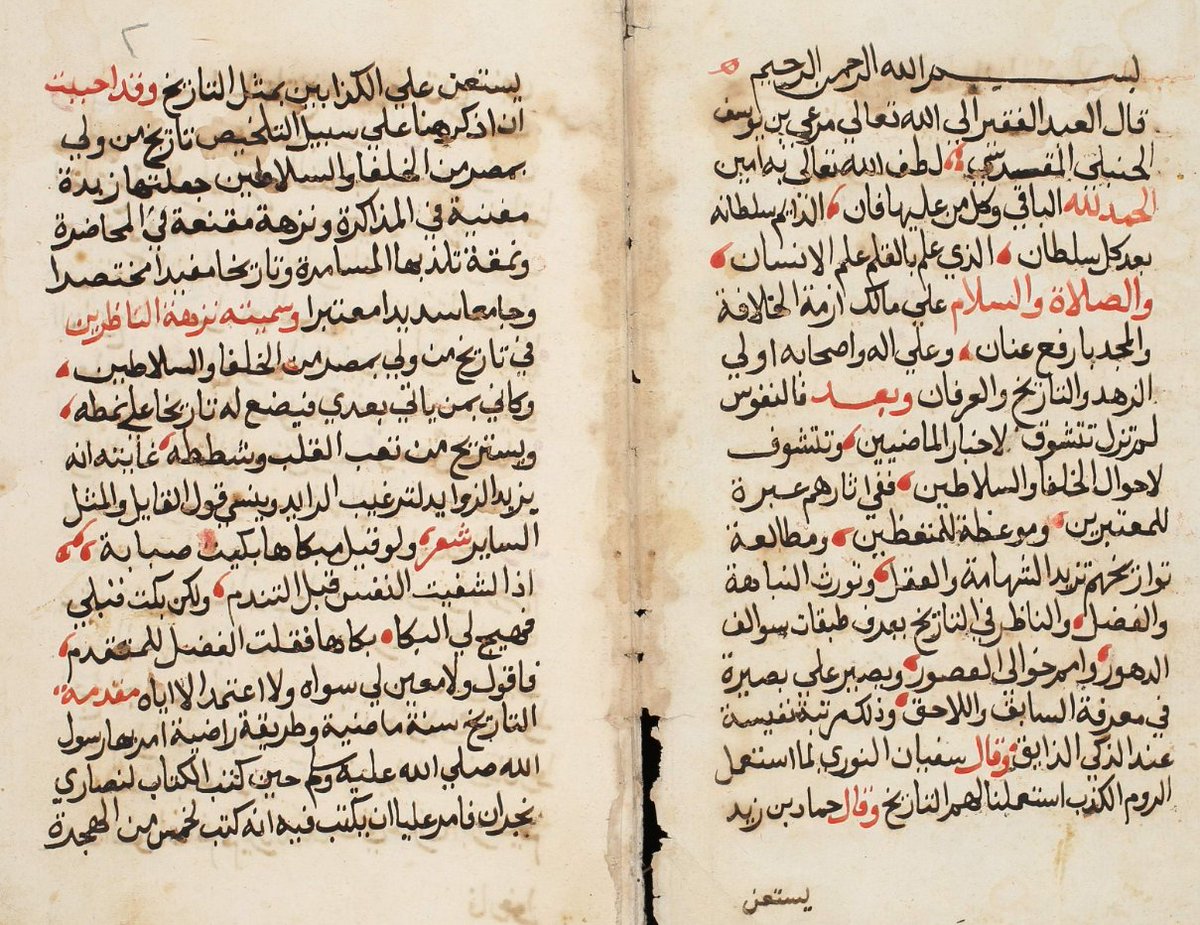

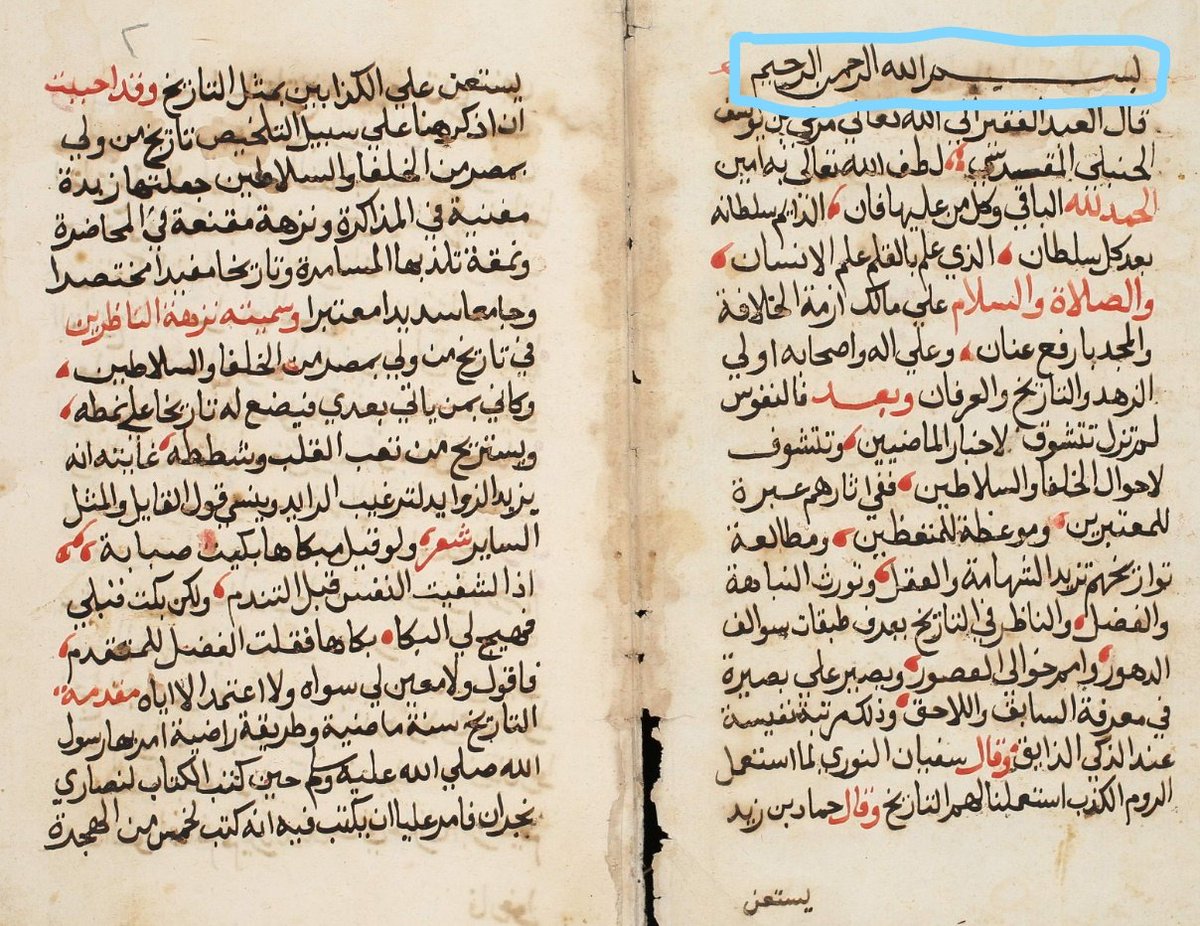

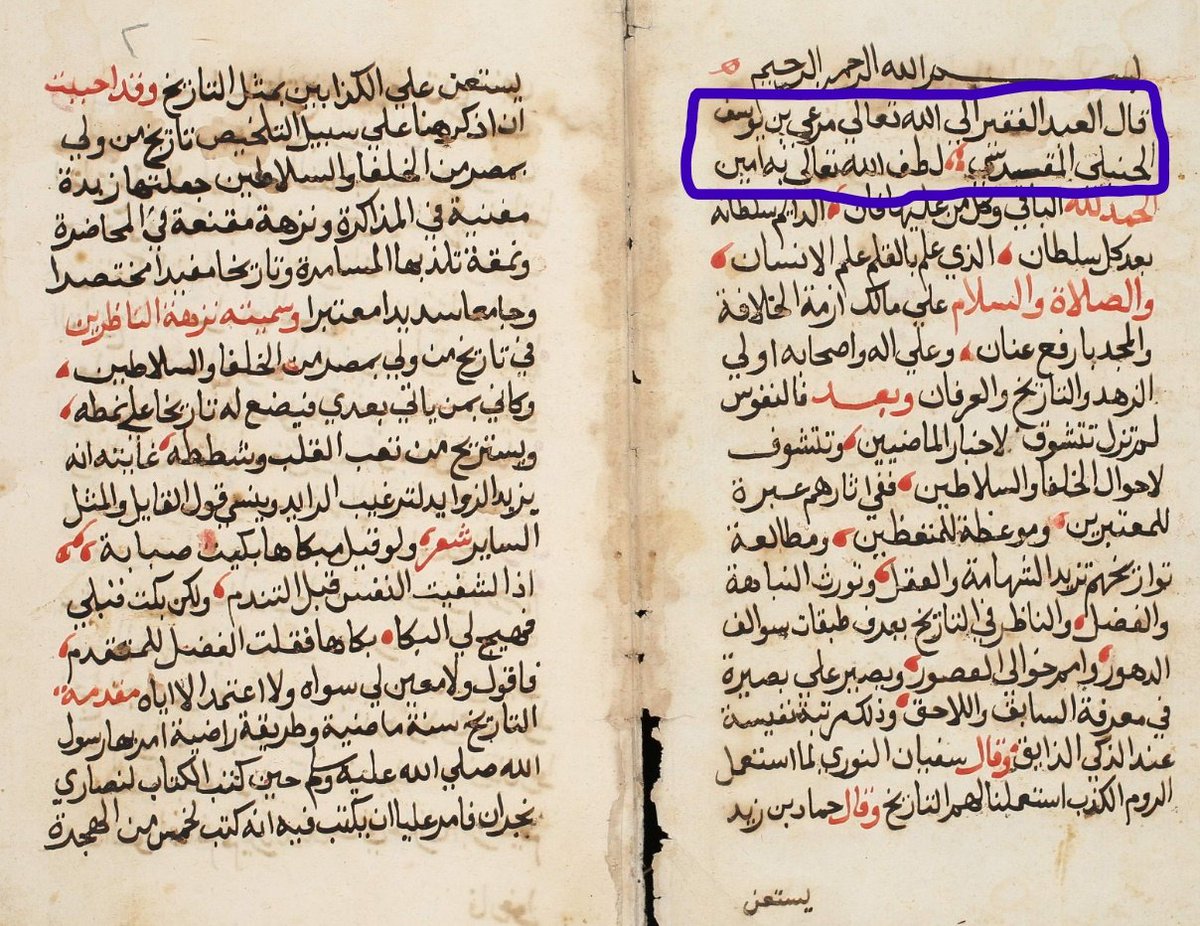

I want to talk about the key textual elements you might find in an Islamic manuscript. I'll focus on this manuscript, roughly 18th century, of an Arabic history of the rulers of Egypt called Nuzhat al-nāẓirīn, by Marʻī al-Karmī (d. 1623/4).

Budeiry Library (Jerusalem) MS 593 -jm

These texts have many elements designed to help the reader understand what they're saying, and choices by the scribe who copied the manuscript often help as well. Let's see what's here. -jm

First, almost every Islamic text begins with the invocation "in the name of God, the compassionate, the merciful." The wording is never changed, and it's always in Arabic, no matter what language the text is, although you might add phrases like "and we ask God for help." -jm

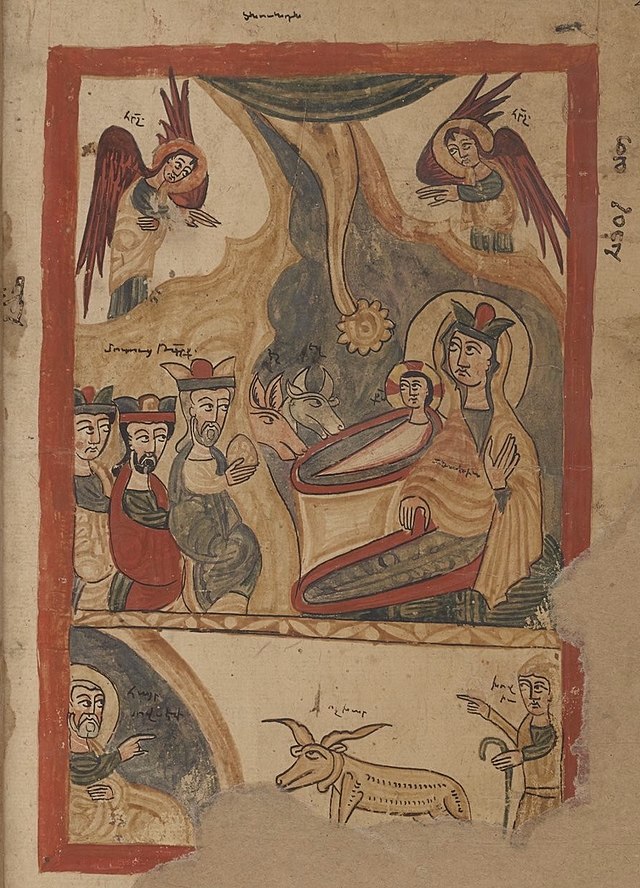

Christians were able to do more experimentation with their invocations, as you can see from the examples here. https://t.co/wEPWRitCWA -jm

After the invocation (basmalah), you might have what this text has, which is an introduction of the author in the form "the poor slave of God [so-and-so] said..." often followed by a quick prayer for the author. -jm

Budeiry Library (Jerusalem) MS 593 -jm

These texts have many elements designed to help the reader understand what they're saying, and choices by the scribe who copied the manuscript often help as well. Let's see what's here. -jm

First, almost every Islamic text begins with the invocation "in the name of God, the compassionate, the merciful." The wording is never changed, and it's always in Arabic, no matter what language the text is, although you might add phrases like "and we ask God for help." -jm

Christians were able to do more experimentation with their invocations, as you can see from the examples here. https://t.co/wEPWRitCWA -jm

These little prayers are fun pic.twitter.com/hJYk2M01bO

— Josh Mugler (@J_mugs) February 16, 2019

After the invocation (basmalah), you might have what this text has, which is an introduction of the author in the form "the poor slave of God [so-and-so] said..." often followed by a quick prayer for the author. -jm

You May Also Like

"I really want to break into Product Management"

make products.

"If only someone would tell me how I can get a startup to notice me."

Make Products.

"I guess it's impossible and I'll never break into the industry."

MAKE PRODUCTS.

Courtesy of @edbrisson's wonderful thread on breaking into comics – https://t.co/TgNblNSCBj – here is why the same applies to Product Management, too.

There is no better way of learning the craft of product, or proving your potential to employers, than just doing it.

You do not need anybody's permission. We don't have diplomas, nor doctorates. We can barely agree on a single standard of what a Product Manager is supposed to do.

But – there is at least one blindingly obvious industry consensus – a Product Manager makes Products.

And they don't need to be kept at the exact right temperature, given endless resource, or carefully protected in order to do this.

They find their own way.

make products.

"If only someone would tell me how I can get a startup to notice me."

Make Products.

"I guess it's impossible and I'll never break into the industry."

MAKE PRODUCTS.

Courtesy of @edbrisson's wonderful thread on breaking into comics – https://t.co/TgNblNSCBj – here is why the same applies to Product Management, too.

"I really want to break into comics"

— Ed Brisson (@edbrisson) December 4, 2018

make comics.

"If only someone would tell me how I can get an editor to notice me."

Make Comics.

"I guess it's impossible and I'll never break into the industry."

MAKE COMICS.

There is no better way of learning the craft of product, or proving your potential to employers, than just doing it.

You do not need anybody's permission. We don't have diplomas, nor doctorates. We can barely agree on a single standard of what a Product Manager is supposed to do.

But – there is at least one blindingly obvious industry consensus – a Product Manager makes Products.

And they don't need to be kept at the exact right temperature, given endless resource, or carefully protected in order to do this.

They find their own way.

Great article from @AsheSchow. I lived thru the 'Satanic Panic' of the 1980's/early 1990's asking myself "Has eveyrbody lost their GODDAMN MINDS?!"

The 3 big things that made the 1980's/early 1990's surreal for me.

1) Satanic Panic - satanism in the day cares ahhhh!

2) "Repressed memory" syndrome

3) Facilitated Communication [FC]

All 3 led to massive abuse.

"Therapists" -and I use the term to describe these quacks loosely - would hypnotize people & convince they they were 'reliving' past memories of Mom & Dad killing babies in Satanic rituals in the basement while they were growing up.

Other 'therapists' would badger kids until they invented stories about watching alligators eat babies dropped into a lake from a hot air balloon. Kids would deny anything happened for hours until the therapist 'broke through' and 'found' the 'truth'.

FC was a movement that started with the claim severely handicapped individuals were able to 'type' legible sentences & communicate if a 'helper' guided their hands over a keyboard.

For three years I have wanted to write an article on moral panics. I have collected anecdotes and similarities between today\u2019s moral panic and those of the past - particularly the Satanic Panic of the 80s.

— Ashe Schow (@AsheSchow) September 29, 2018

This is my finished product: https://t.co/otcM1uuUDk

The 3 big things that made the 1980's/early 1990's surreal for me.

1) Satanic Panic - satanism in the day cares ahhhh!

2) "Repressed memory" syndrome

3) Facilitated Communication [FC]

All 3 led to massive abuse.

"Therapists" -and I use the term to describe these quacks loosely - would hypnotize people & convince they they were 'reliving' past memories of Mom & Dad killing babies in Satanic rituals in the basement while they were growing up.

Other 'therapists' would badger kids until they invented stories about watching alligators eat babies dropped into a lake from a hot air balloon. Kids would deny anything happened for hours until the therapist 'broke through' and 'found' the 'truth'.

FC was a movement that started with the claim severely handicapped individuals were able to 'type' legible sentences & communicate if a 'helper' guided their hands over a keyboard.