According to popular legend, Patient Zero of the 1883 cholera epidemic was a mason in his mid-forties named Ḥassan Nūr-al-Dīn, who lived in the port city of Damietta (34,000 people). (2/19)

Happy Friday! I'm @khowaga, and I'm talking about the social history of medicine and disease in #Egypt. Today's topic is the cholera of 1883. (1/19)

#tweetistorian #twitterstorians #histmed #epitwitter

According to popular legend, Patient Zero of the 1883 cholera epidemic was a mason in his mid-forties named Ḥassan Nūr-al-Dīn, who lived in the port city of Damietta (34,000 people). (2/19)

In short, this time it was him, but it could have been you or me. (6/19)

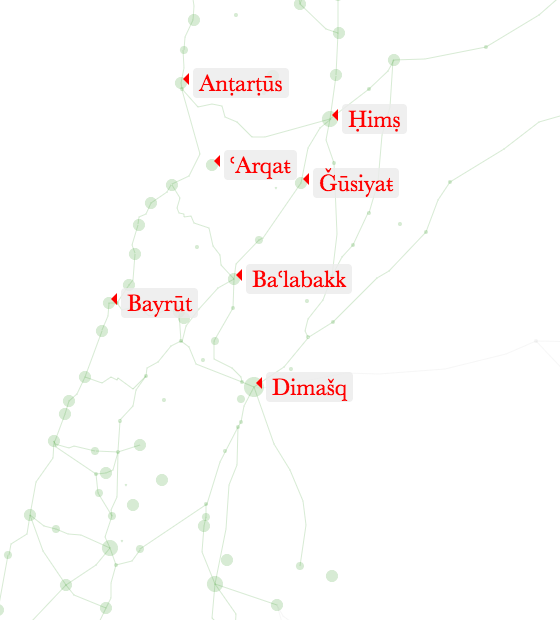

When the disease began to appear outside of India, there was immediate concern about the possibility that it would appear along shipping lines. And the British, as the newly dominant imperial force in South Asia, stood to lose the most. (9/19)

More from Tweeting Historians

More from History

You May Also Like

It was Ved Vyas who edited the eighteen thousand shlokas of Bhagwat. This book destroys all your sins. It has twelve parts which are like kalpvraksh.

In the first skandh, the importance of Vedvyas

and characters of Pandavas are described by the dialogues between Suutji and Shaunakji. Then there is the story of Parikshit.

Next there is a Brahm Narad dialogue describing the avtaar of Bhagwan. Then the characteristics of Puraan are mentioned.

It also discusses the evolution of universe.( https://t.co/2aK1AZSC79 )

Next is the portrayal of Vidur and his dialogue with Maitreyji. Then there is a mention of Creation of universe by Brahma and the preachings of Sankhya by Kapil Muni.

HOW LIFE EVOLVED IN THIS UNIVERSE AS PER OUR SCRIPTURES.

— Anshul Pandey (@Anshulspiritual) August 29, 2020

Well maximum of Living being are the Vansaj of Rishi Kashyap. I have tried to give stories from different-different Puran. So lets start.... pic.twitter.com/MrrTS4xORk

In the next section we find the portrayal of Sati, Dhruv, Pruthu, and the story of ancient King, Bahirshi.

In the next section we find the character of King Priyavrat and his sons, different types of loks in this universe, and description of Narak. ( https://t.co/gmDTkLktKS )

Thread on NARK(HELL) / \u0928\u0930\u094d\u0915

— Anshul Pandey (@Anshulspiritual) August 11, 2020

Well today i will take you to a journey where nobody wants to go i.e Nark. Hence beware of doing Adharma/Evil things. There are various mentions in Puranas about Nark, But my Thread is only as per Bhagwat puran(SS attached in below Thread)

1/8 pic.twitter.com/raHYWtB53Q

In the sixth part we find the portrayal of Ajaamil ( https://t.co/LdVSSNspa2 ), Daksh and the birth of Marudgans( https://t.co/tecNidVckj )

In the seventh section we find the story of Prahlad and the description of Varnashram dharma. This section is based on karma vaasna.

#THREAD

— Anshul Pandey (@Anshulspiritual) August 12, 2020

WHY PARENTS CHOOSE RELIGIOUS OR PARAMATMA'S NAMES FOR THEIR CHILDREN AND WHICH ARE THE EASIEST WAY TO WASH AWAY YOUR SINS.

Yesterday I had described the types of Naraka's and the Sin or Adharma for a person to be there.

1/8 pic.twitter.com/XjPB2hfnUC