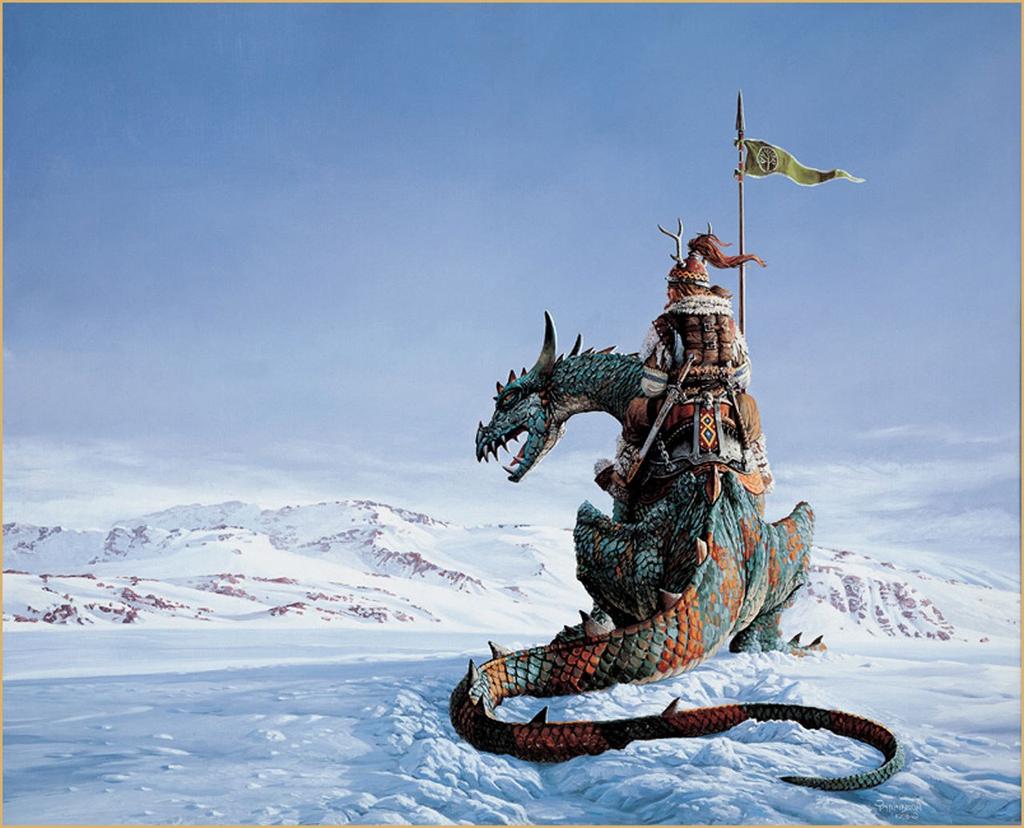

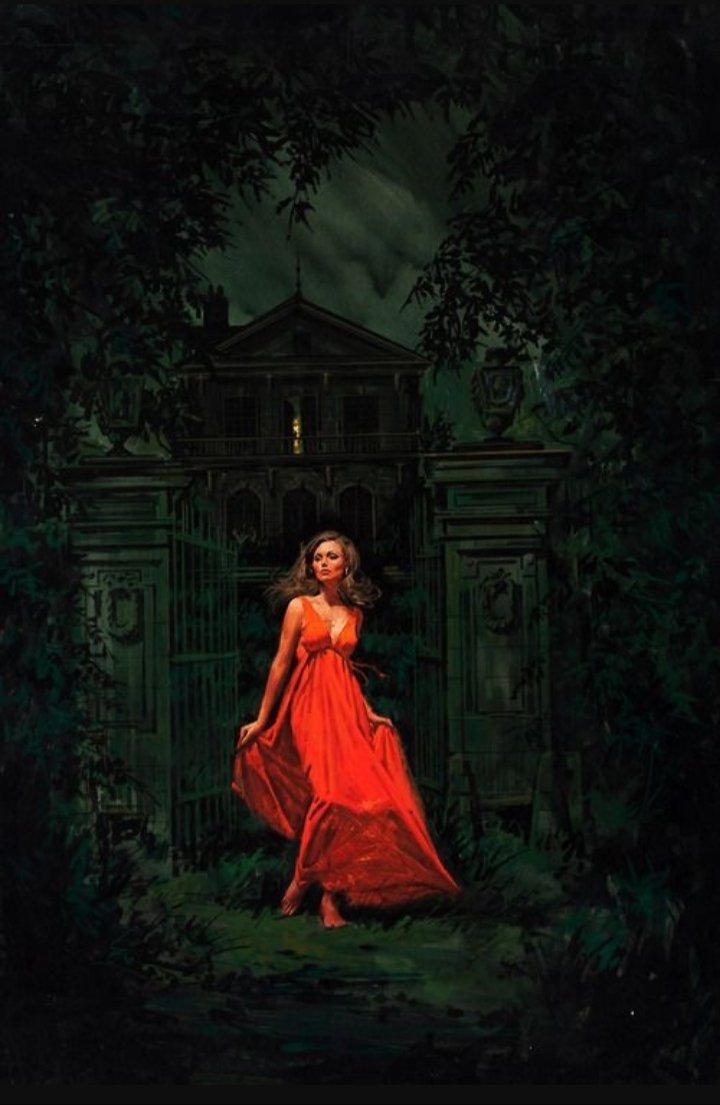

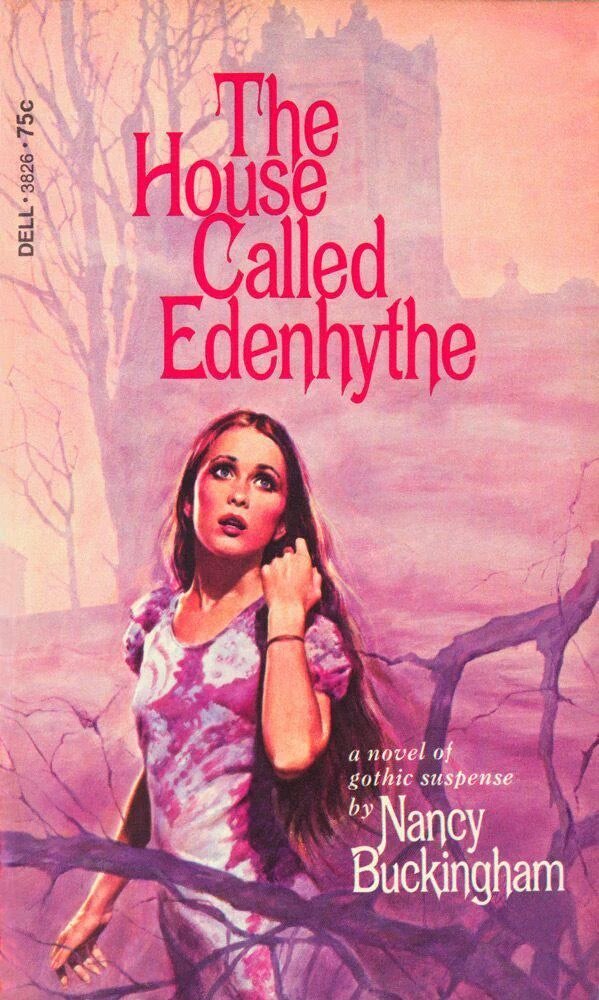

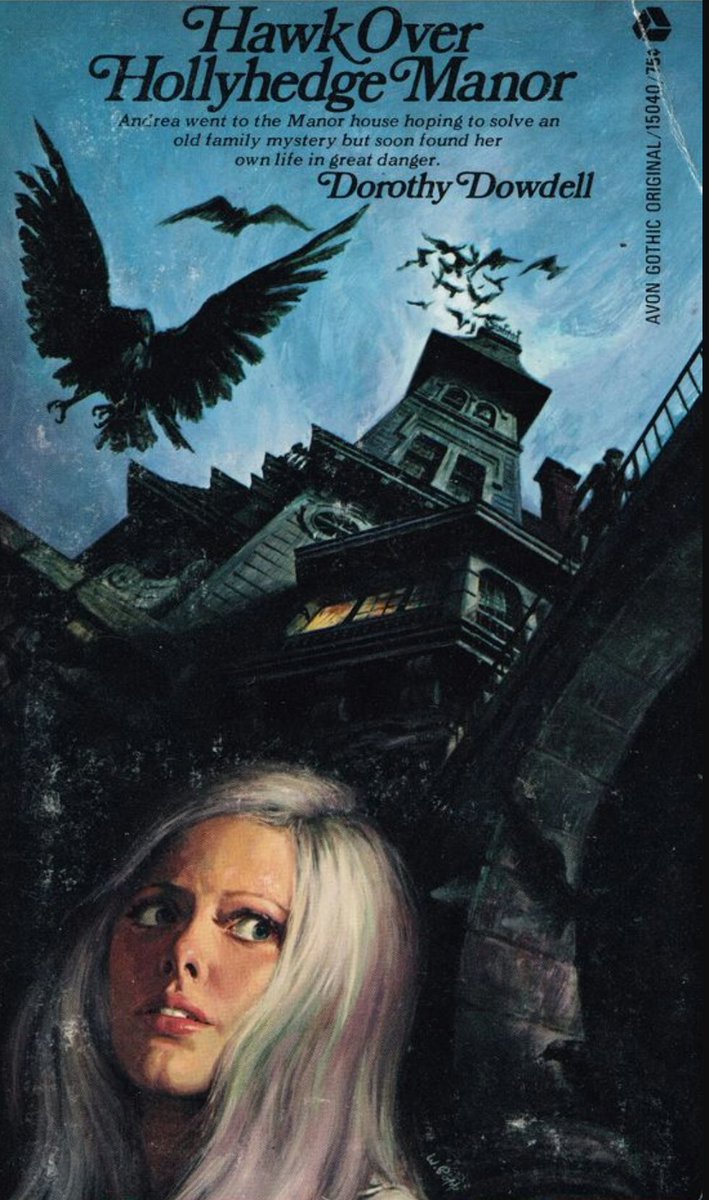

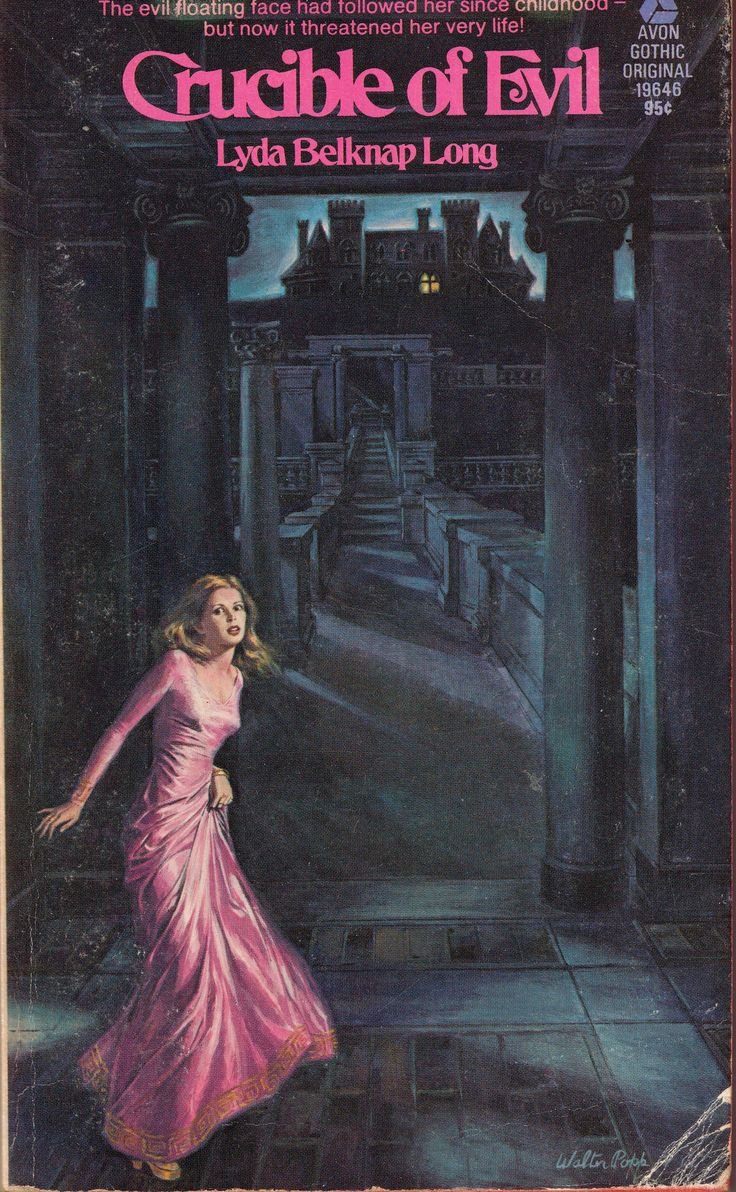

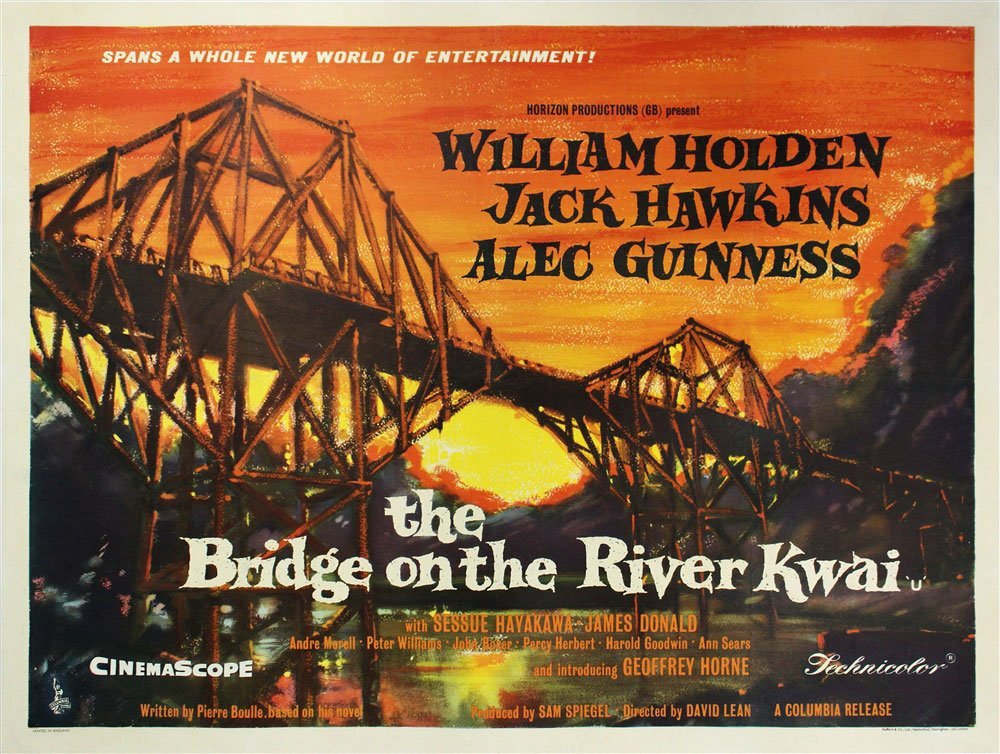

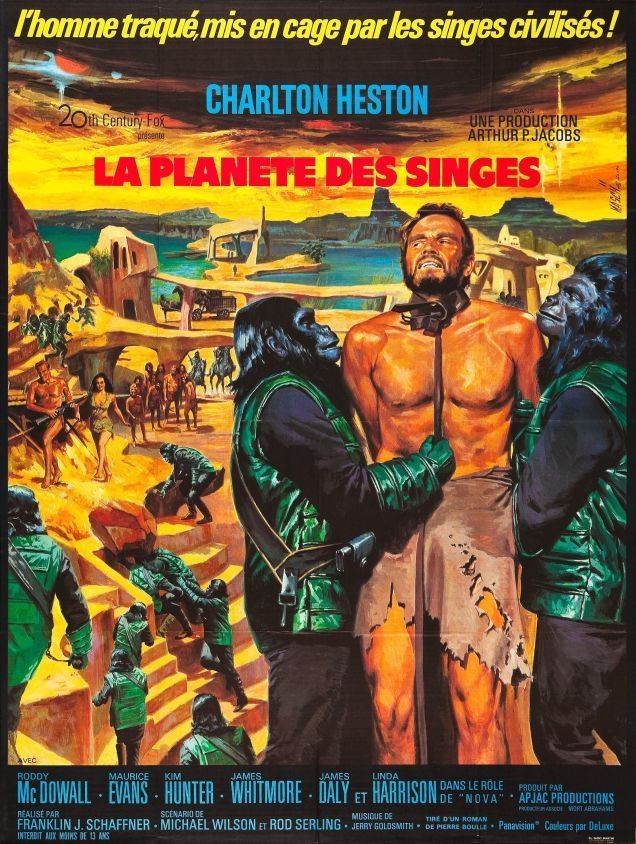

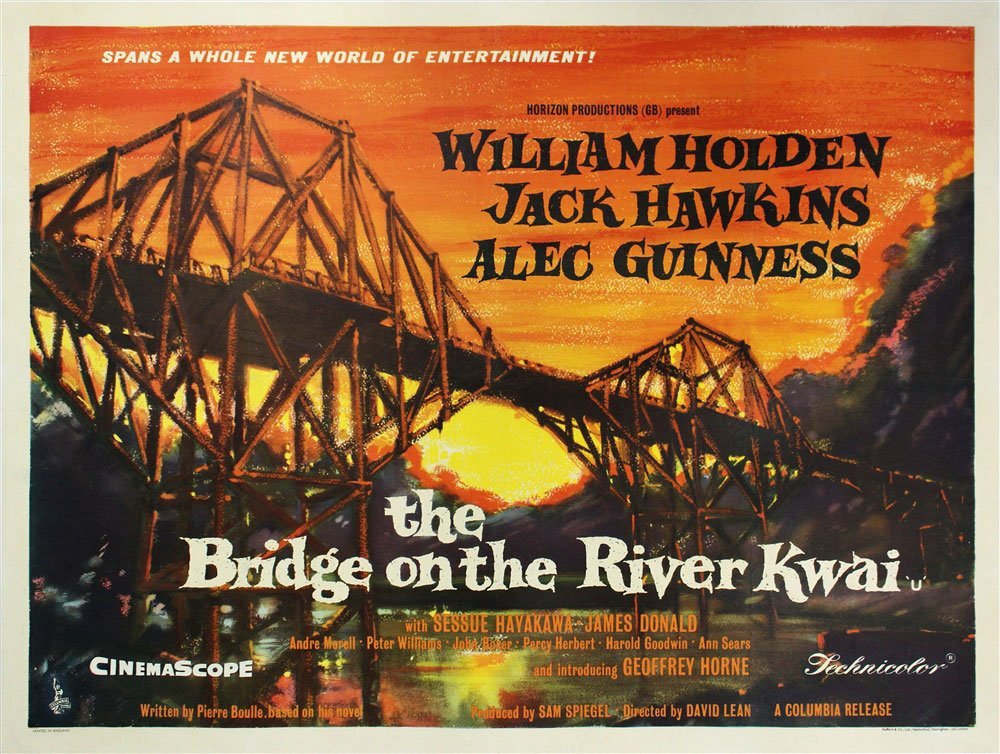

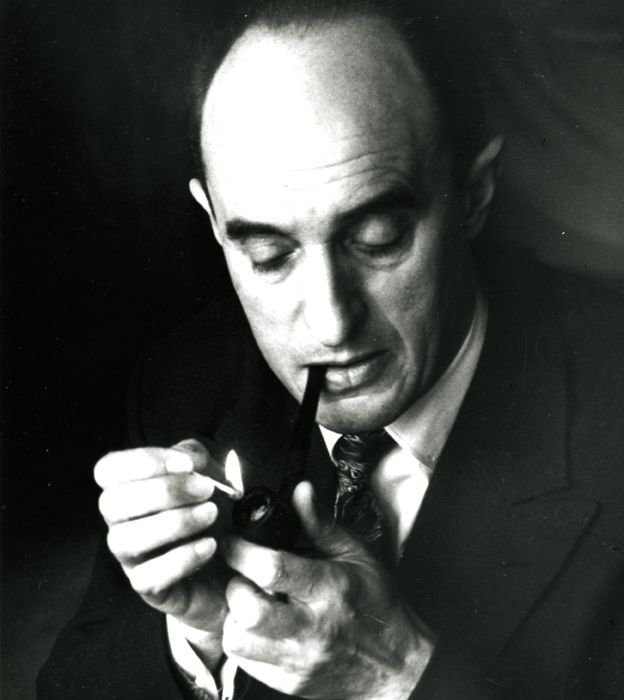

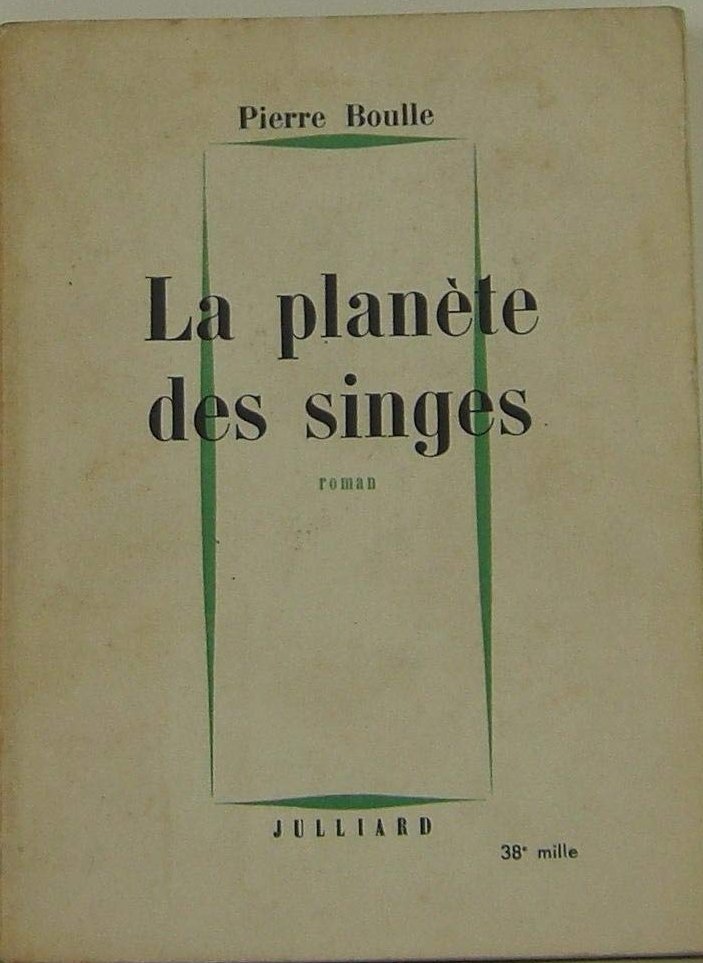

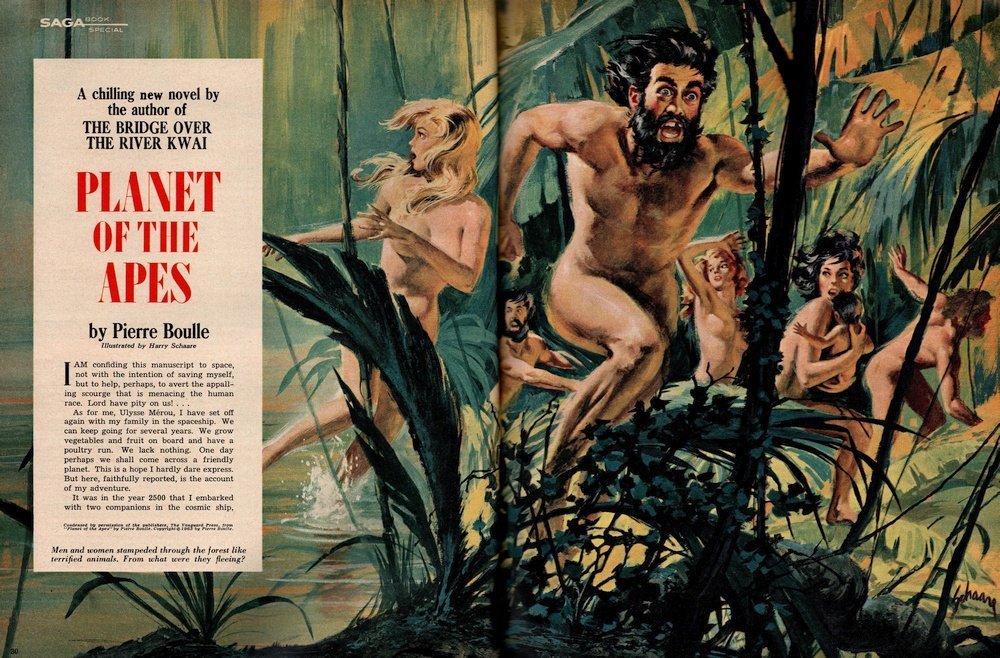

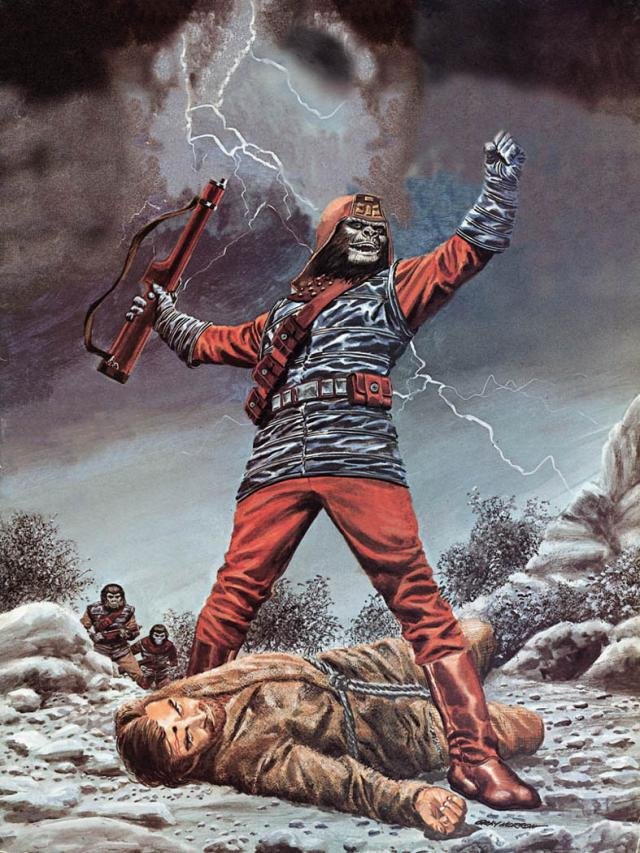

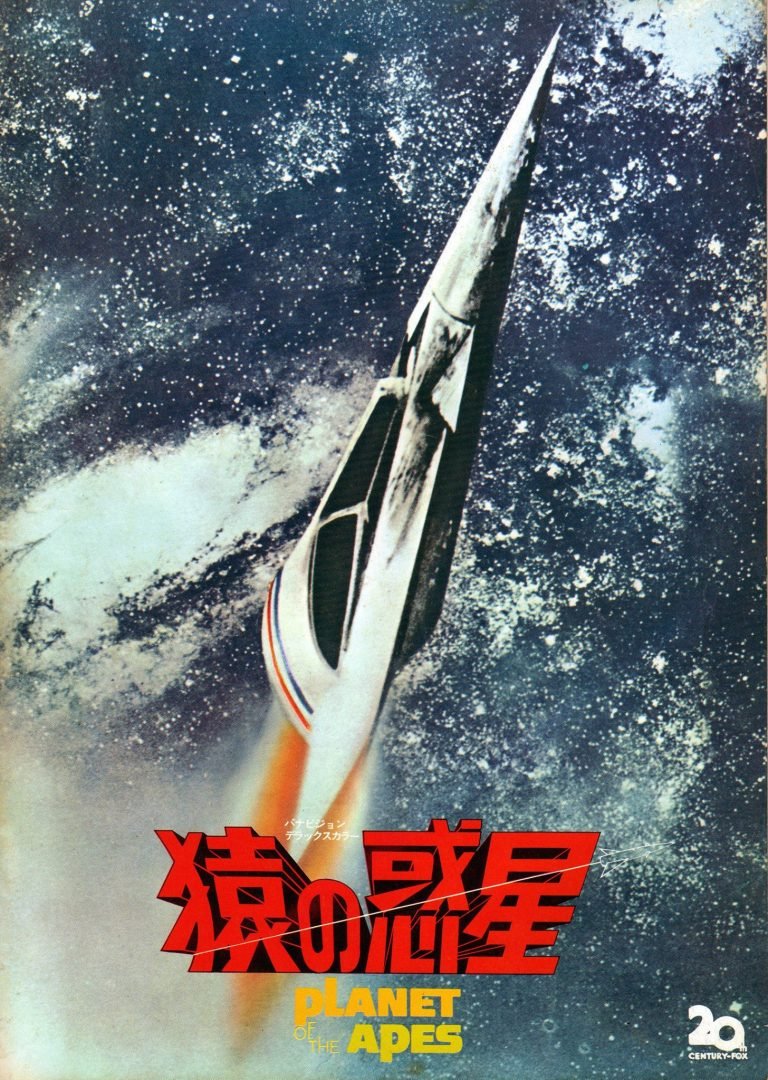

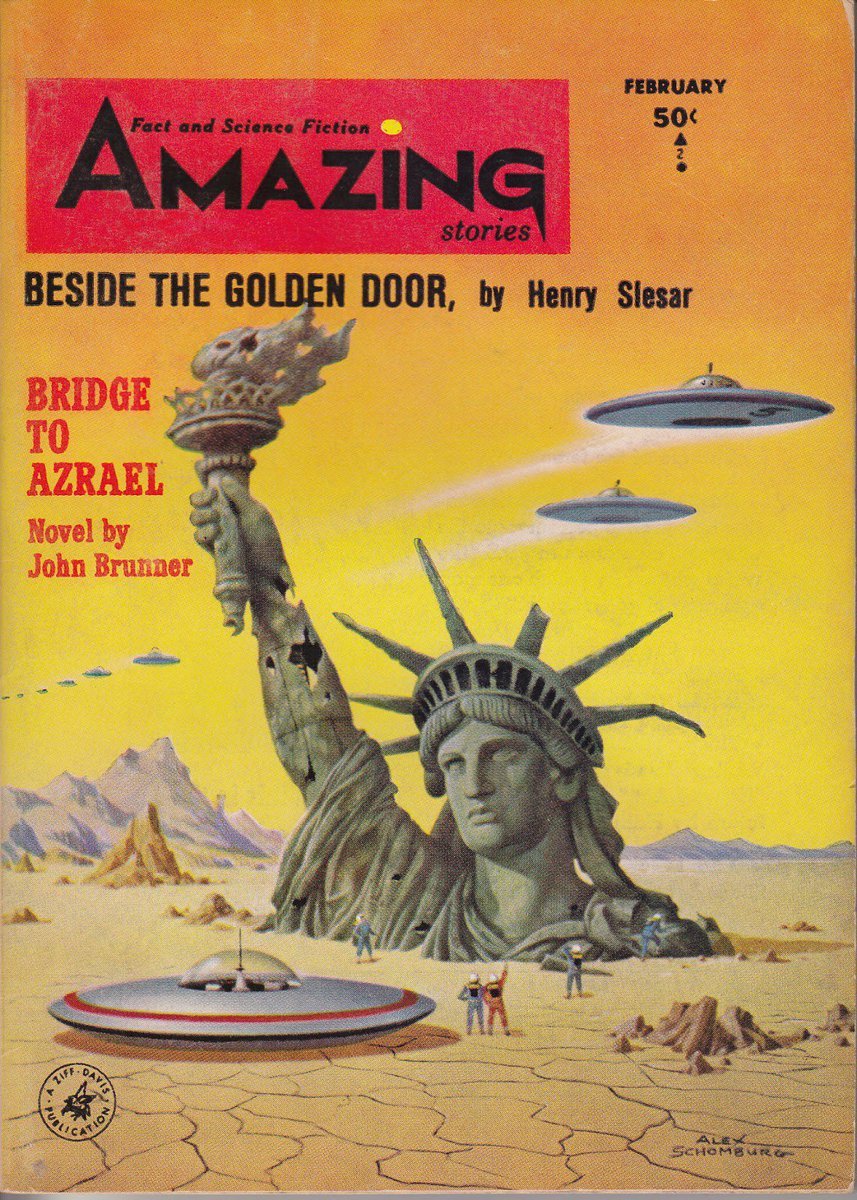

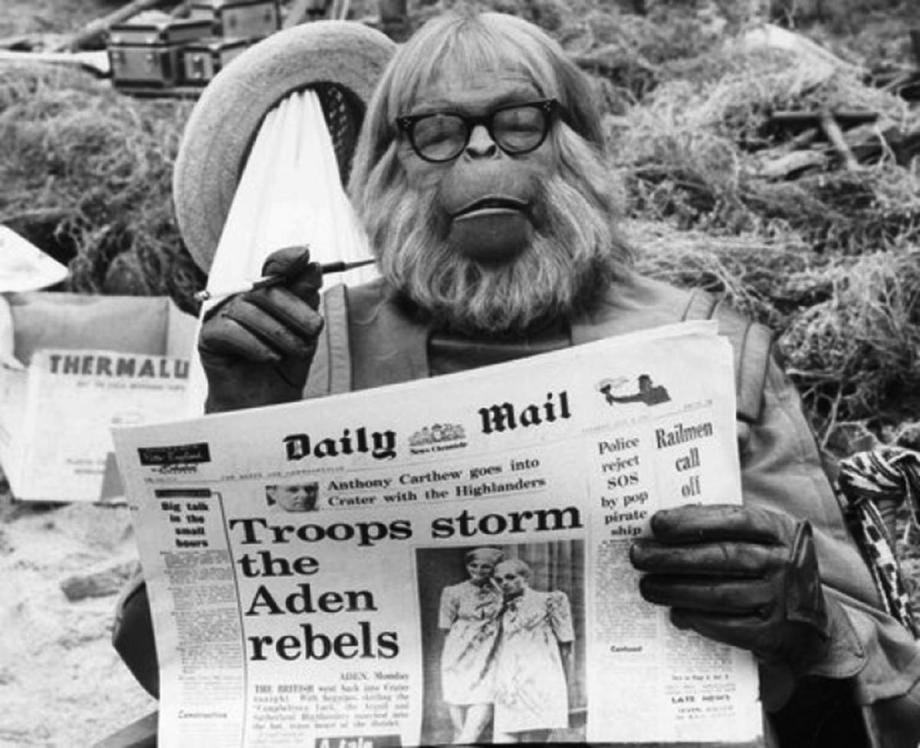

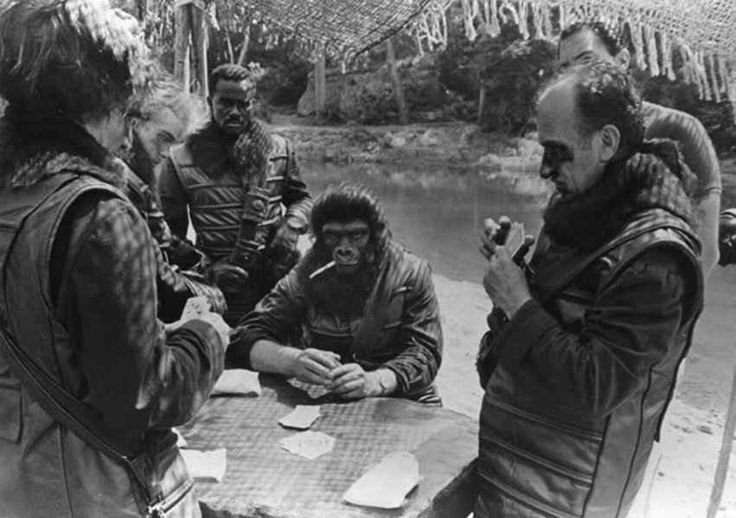

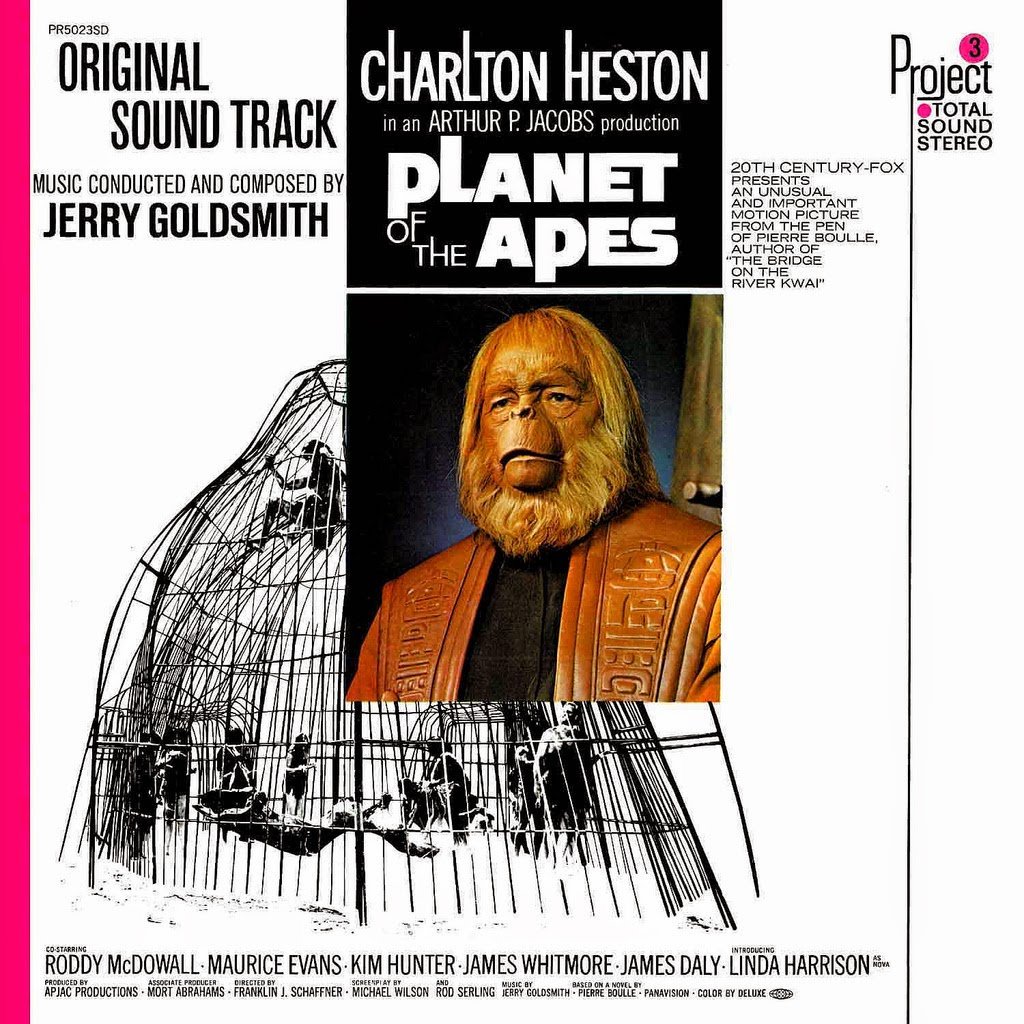

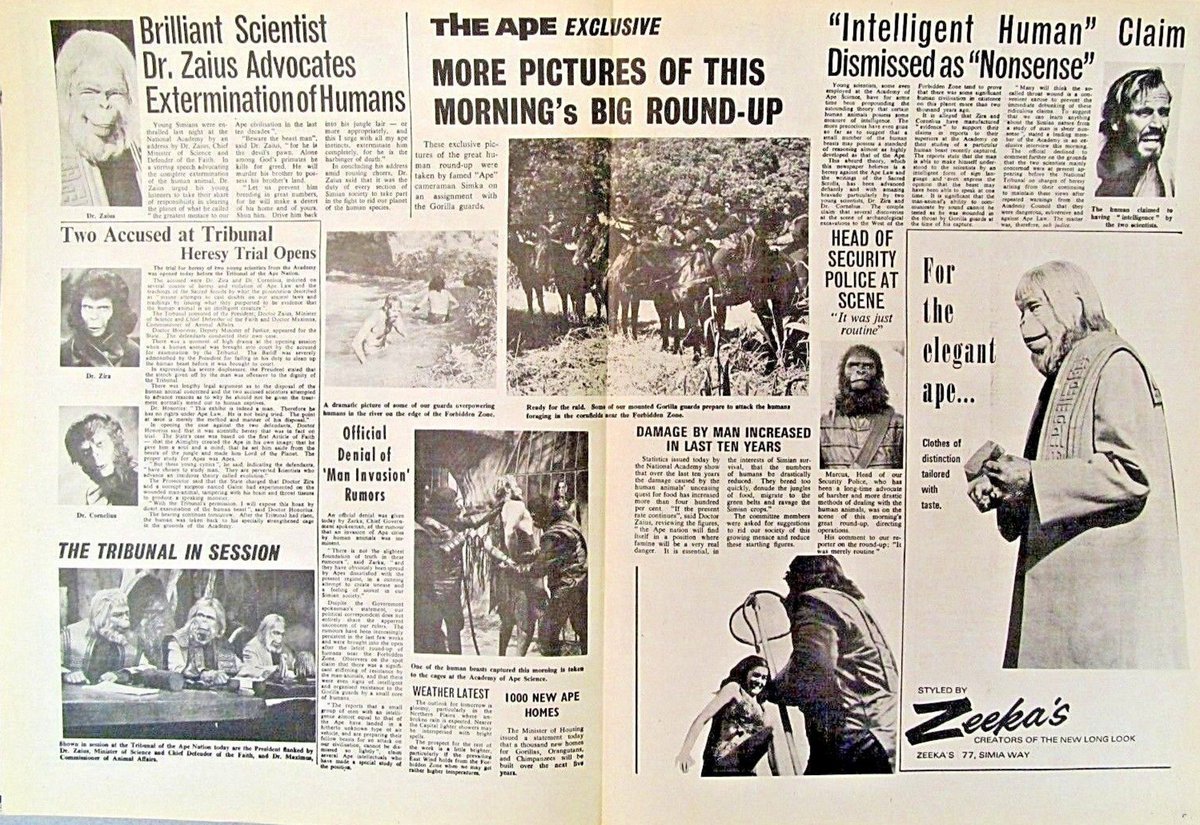

Pierre Boulle was born today in 1912, so what better time to look back at his sociological science-fiction classic that paved the way for Star Wars and the MCU.

This is the story of Planet Of The Apes!

The travellers chuckle at this tale: as civilised chimps they know no brute human could become so advanced.

But for me it's legacy was something else...

More from Pulp Librarian

More from Culture

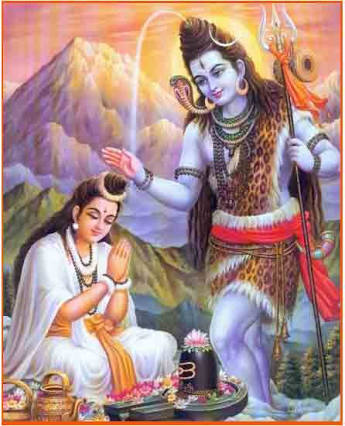

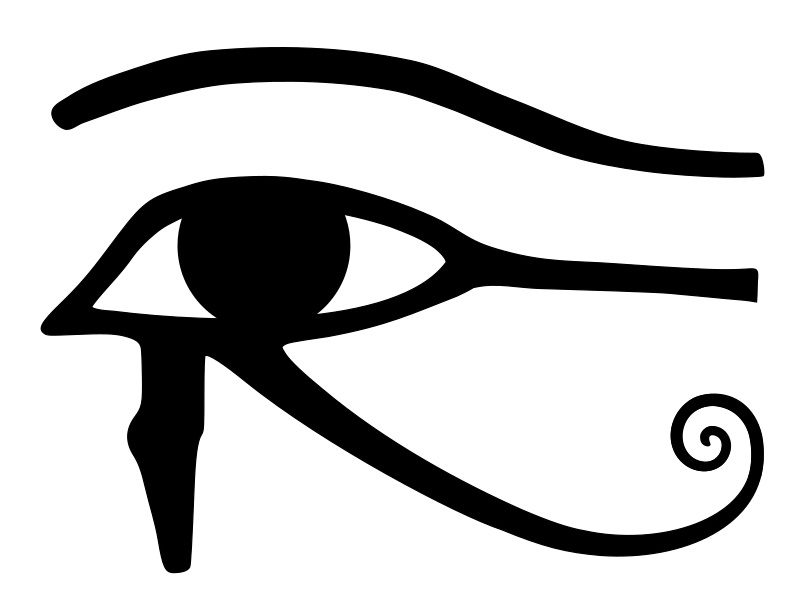

The Eye of Horus. 1/*

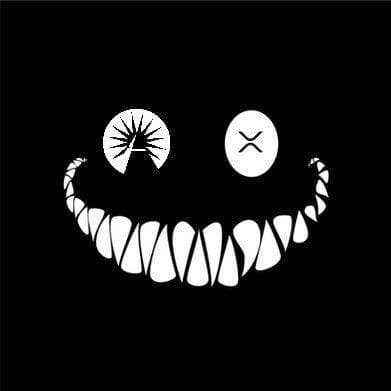

I believe that @ripple_crippler and @looP_rM311_7211 are the same person. I know, nobody believes that. 2/*

Today I want to prove that Mr Pool smile faces mean XRP and price increase. In Ripple_Crippler, previous to Mr Pool existence, smile faces were frequent. They were very similar to the ones Mr Pool posts. The eyes also were usually a couple of "x", in fact, XRP logo. 3/*

The smile XRP-eyed face also appears related to the Moon. XRP going to the Moon. 4/*

And smile XRP-eyed faces also appear related to Egypt. In particular, to the Eye of Horus. https://t.co/i4rRzuQ0gZ 5/*

I believe that @ripple_crippler and @looP_rM311_7211 are the same person. I know, nobody believes that. 2/*

Today I want to prove that Mr Pool smile faces mean XRP and price increase. In Ripple_Crippler, previous to Mr Pool existence, smile faces were frequent. They were very similar to the ones Mr Pool posts. The eyes also were usually a couple of "x", in fact, XRP logo. 3/*

The smile XRP-eyed face also appears related to the Moon. XRP going to the Moon. 4/*

And smile XRP-eyed faces also appear related to Egypt. In particular, to the Eye of Horus. https://t.co/i4rRzuQ0gZ 5/*

. THREAD 1/x

David Baddiel is getting lots of coverage and feedback on his book which again focuses on so called 'left wing' antisemitism.

I will start by saying that I have seen antisemitic comments made by Labour members and some genuine cases.

However, I have huge concerns.

2/x

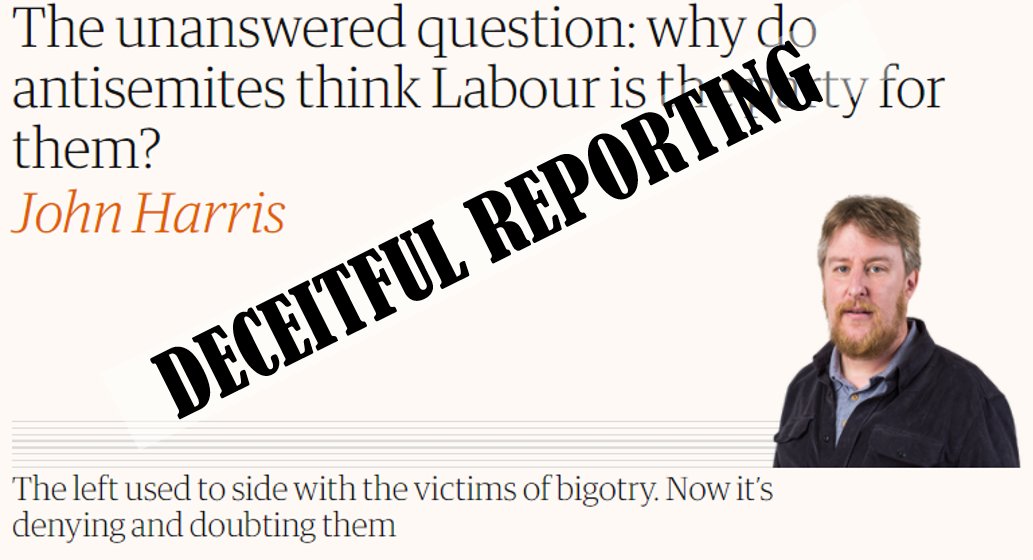

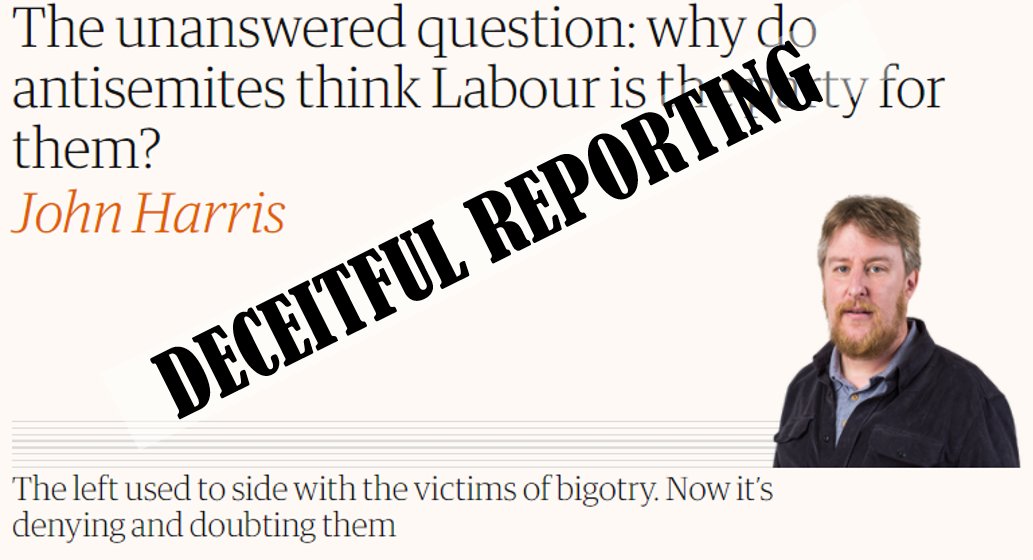

Let's look in detail at this article written in April 2019 in the @Guardian - and I will explain the concerns.

The areas highlighted guide you to believe this was all Labour - IT WASN'T.

It also occurred before 2015! Detail follows...

https://t.co/cK59FP83aG

3/x

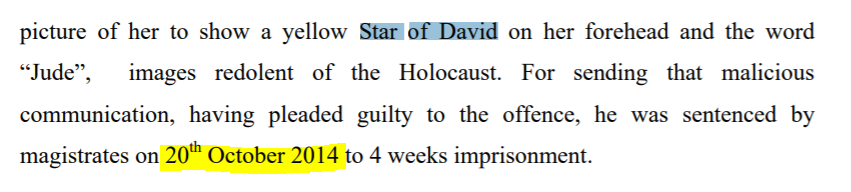

So as you see the writer of this rather deceitful piece starts with

"THAT CHANGED IN SEPTEMBER 2015" 🙄

This was done to point the timeframe as Corbyn's leadership. Yet the article goes on to describe things that are not even related to Labour, which occurred in 2014.

4/x

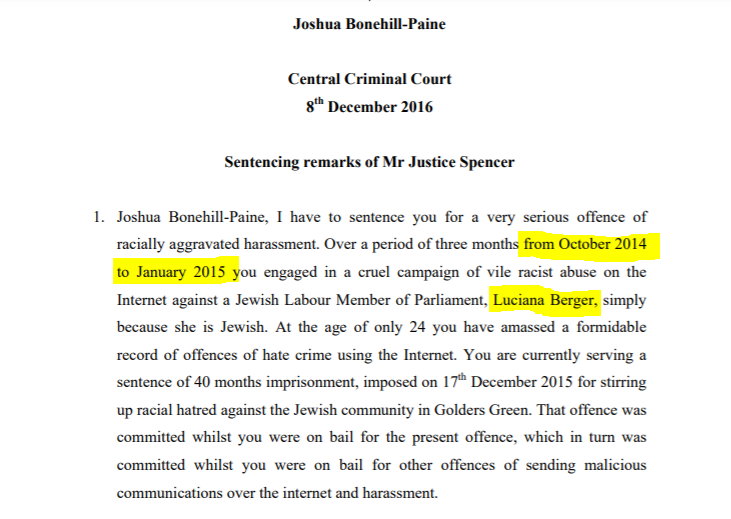

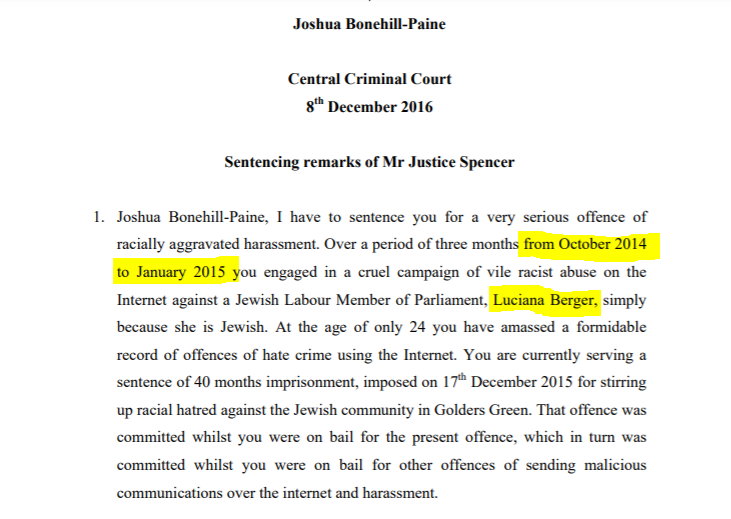

So... What in fact the @Guardian writer is discussing here is this case - where a group of Neo-Nazi's spent months inflicting abuse on Jewish MP Luciana Berger

All the detail is in the Court Notes when Bonehill-Paine was sentenced by the judge.

https://t.co/wAyo6Yro5Q

5/x

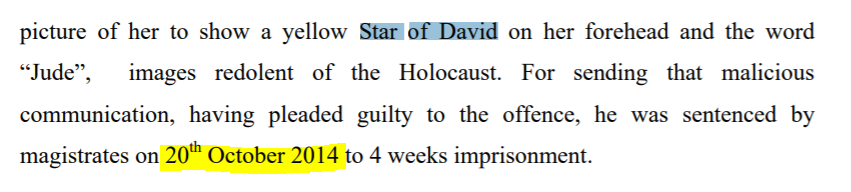

The Justice sentencing remarks to Neo-Nazi explain the previous cases too. See the date 2014.

Yet the Guardian writer refers to this NON LABOUR case to effectively make her article a lie.

"Star of David" - this was Garron Helm another neo-Nazi..

David Baddiel is getting lots of coverage and feedback on his book which again focuses on so called 'left wing' antisemitism.

I will start by saying that I have seen antisemitic comments made by Labour members and some genuine cases.

However, I have huge concerns.

2/x

Let's look in detail at this article written in April 2019 in the @Guardian - and I will explain the concerns.

The areas highlighted guide you to believe this was all Labour - IT WASN'T.

It also occurred before 2015! Detail follows...

https://t.co/cK59FP83aG

3/x

So as you see the writer of this rather deceitful piece starts with

"THAT CHANGED IN SEPTEMBER 2015" 🙄

This was done to point the timeframe as Corbyn's leadership. Yet the article goes on to describe things that are not even related to Labour, which occurred in 2014.

4/x

So... What in fact the @Guardian writer is discussing here is this case - where a group of Neo-Nazi's spent months inflicting abuse on Jewish MP Luciana Berger

All the detail is in the Court Notes when Bonehill-Paine was sentenced by the judge.

https://t.co/wAyo6Yro5Q

5/x

The Justice sentencing remarks to Neo-Nazi explain the previous cases too. See the date 2014.

Yet the Guardian writer refers to this NON LABOUR case to effectively make her article a lie.

"Star of David" - this was Garron Helm another neo-Nazi..

You May Also Like

1/ 👋 Excited to share what we’ve been building at https://t.co/GOQJ7LjQ2t + we are going to tweetstorm our progress every week!

Week 1 highlights: getting shortlisted for YC W2019🤞, acquiring a premium domain💰, meeting Substack's @hamishmckenzie and Stripe CEO @patrickc 🤩

2/ So what is Brew?

brew / bru : / to make (beer, coffee etc.) / verb: begin to develop 🌱

A place for you to enjoy premium content while supporting your favorite creators. Sort of like a ‘Consumer-facing Patreon’ cc @jackconte

(we’re still working on the pitch)

3/ So, why be so transparent? Two words: launch strategy.

jk 😅 a) I loooove doing something consistently for a long period of time b) limited downside and infinite upside (feedback, accountability, reach).

cc @altimor, @pmarca

4/ https://t.co/GOQJ7LjQ2t domain 🍻

It started with a cold email. Guess what? He was using BuyMeACoffee on his blog, and was excited to hear about what we're building next. Within 2w, we signed the deal at @Escrowcom's SF office. You’re a pleasure to work with @MichaelCyger!

5/ @ycombinator's invite for the in-person interview arrived that evening. Quite a day!

Thanks @patio11 for the thoughtful feedback on our YC application, and @gabhubert for your directions on positioning the product — set the tone for our pitch!

Week 1 highlights: getting shortlisted for YC W2019🤞, acquiring a premium domain💰, meeting Substack's @hamishmckenzie and Stripe CEO @patrickc 🤩

2/ So what is Brew?

brew / bru : / to make (beer, coffee etc.) / verb: begin to develop 🌱

A place for you to enjoy premium content while supporting your favorite creators. Sort of like a ‘Consumer-facing Patreon’ cc @jackconte

(we’re still working on the pitch)

3/ So, why be so transparent? Two words: launch strategy.

jk 😅 a) I loooove doing something consistently for a long period of time b) limited downside and infinite upside (feedback, accountability, reach).

cc @altimor, @pmarca

4/ https://t.co/GOQJ7LjQ2t domain 🍻

It started with a cold email. Guess what? He was using BuyMeACoffee on his blog, and was excited to hear about what we're building next. Within 2w, we signed the deal at @Escrowcom's SF office. You’re a pleasure to work with @MichaelCyger!

5/ @ycombinator's invite for the in-person interview arrived that evening. Quite a day!

Thanks @patio11 for the thoughtful feedback on our YC application, and @gabhubert for your directions on positioning the product — set the tone for our pitch!