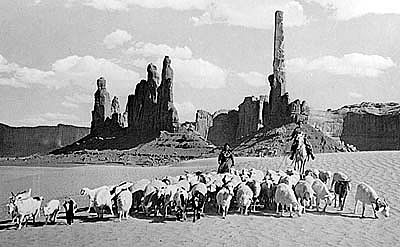

This Day in Labor History: February 14, 1940. A group of Navajos write a letter of protest against the livestock reduction program the government forced upon them. Let's talk about how the New Deal transformed Navajo work culture in a shockingly negative way.

For instance, in our own district (No.3) the sheep unit is set at 282. If a person has 5 horses, that would be the equivalent to 25 sheep; 1 head of cattle is the equivalent of 4 sheep....

More from Erik Loomis

More from History

You May Also Like

Decoded his way of analysis/logics for everyone to easily understand.

Have covered:

1. Analysis of volatility, how to foresee/signs.

2. Workbook

3. When to sell options

4. Diff category of days

5. How movement of option prices tell us what will happen

1. Keeps following volatility super closely.

Makes 7-8 different strategies to give him a sense of what's going on.

Whichever gives highest profit he trades in.

I am quite different from your style. I follow the market's volatility very closely. I have mock positions in 7-8 different strategies which allows me to stay connected. Whichever gives best profit is usually the one i trade in.

— Sarang Sood (@SarangSood) August 13, 2019

2. Theta falls when market moves.

Falls where market is headed towards not on our original position.

Anilji most of the time these days Theta only falls when market moves. So the Theta actually falls where market has moved to, not where our position was in the first place. By shifting we can come close to capturing the Theta fall but not always.

— Sarang Sood (@SarangSood) June 24, 2019

3. If you're an options seller then sell only when volatility is dropping, there is a high probability of you making the right trade and getting profit as a result

He believes in a market operator, if market mover sells volatility Sarang Sir joins him.

This week has been great so far. The main aim is to be in the right side of the volatility, rest the market will reward.

— Sarang Sood (@SarangSood) July 3, 2019

4. Theta decay vs Fall in vega

Sell when Vega is falling rather than for theta decay. You won't be trapped and higher probability of making profit.

There is a difference between theta decay & fall in vega. Decay is certain but there is no guaranteed profit as delta moves can increase cost. Fall in vega on the other hand is backed by a powerful force that sells options and gives handsome returns. Our job is to identify them.

— Sarang Sood (@SarangSood) February 12, 2020

Ironies of Luck https://t.co/5BPWGbAxFi

— Morgan Housel (@morganhousel) March 14, 2018

"Luck is the flip side of risk. They are mirrored cousins, driven by the same thing: You are one person in a 7 billion player game, and the accidental impact of other people\u2019s actions can be more consequential than your own."

I’ve always felt that the luckiest people I know had a talent for recognizing circumstances, not of their own making, that were conducive to a favorable outcome and their ability to quickly take advantage of them.

In other words, dumb luck was just that, it required no awareness on the person’s part, whereas “smart” luck involved awareness followed by action before the circumstances changed.

So, was I “lucky” to be born when I was—nothing I had any control over—and that I came of age just as huge databases and computers were advancing to the point where I could use those tools to write “What Works on Wall Street?” Absolutely.

Was I lucky to start my stock market investments near the peak of interest rates which allowed me to spend the majority of my adult life in a falling rate environment? Yup.