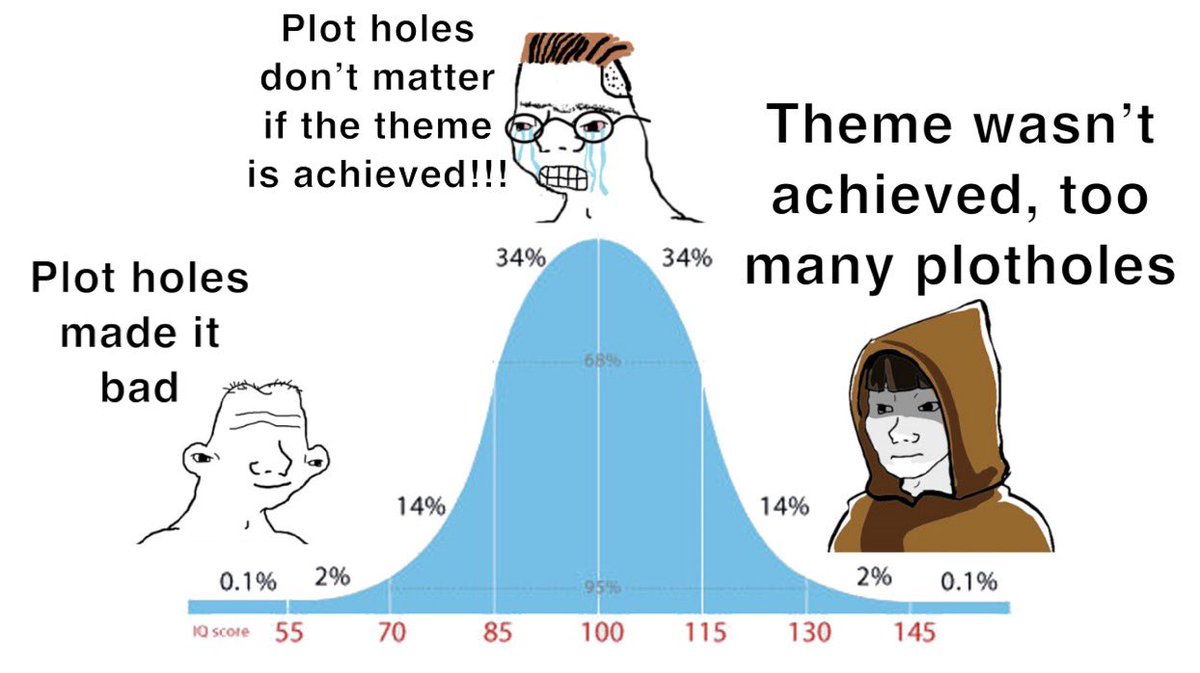

The story is the thing itself. Greater than the sum of its parts. When a story works, theme arises interstitially like harmony, and you are convinced because of the story’s spiritual truth and internal logic.

My friend, you lost.

More from All

You May Also Like

A brief analysis and comparison of the CSS for Twitter's PWA vs Twitter's legacy desktop website. The difference is dramatic and I'll touch on some reasons why.

Legacy site *downloads* ~630 KB CSS per theme and writing direction.

6,769 rules

9,252 selectors

16.7k declarations

3,370 unique declarations

44 media queries

36 unique colors

50 unique background colors

46 unique font sizes

39 unique z-indices

https://t.co/qyl4Bt1i5x

PWA *incrementally generates* ~30 KB CSS that handles all themes and writing directions.

735 rules

740 selectors

757 declarations

730 unique declarations

0 media queries

11 unique colors

32 unique background colors

15 unique font sizes

7 unique z-indices

https://t.co/w7oNG5KUkJ

The legacy site's CSS is what happens when hundreds of people directly write CSS over many years. Specificity wars, redundancy, a house of cards that can't be fixed. The result is extremely inefficient and error-prone styling that punishes users and developers.

The PWA's CSS is generated on-demand by a JS framework that manages styles and outputs "atomic CSS". The framework can enforce strict constraints and perform optimisations, which is why the CSS is so much smaller and safer. Style conflicts and unbounded CSS growth are avoided.

Legacy site *downloads* ~630 KB CSS per theme and writing direction.

6,769 rules

9,252 selectors

16.7k declarations

3,370 unique declarations

44 media queries

36 unique colors

50 unique background colors

46 unique font sizes

39 unique z-indices

https://t.co/qyl4Bt1i5x

PWA *incrementally generates* ~30 KB CSS that handles all themes and writing directions.

735 rules

740 selectors

757 declarations

730 unique declarations

0 media queries

11 unique colors

32 unique background colors

15 unique font sizes

7 unique z-indices

https://t.co/w7oNG5KUkJ

The legacy site's CSS is what happens when hundreds of people directly write CSS over many years. Specificity wars, redundancy, a house of cards that can't be fixed. The result is extremely inefficient and error-prone styling that punishes users and developers.

The PWA's CSS is generated on-demand by a JS framework that manages styles and outputs "atomic CSS". The framework can enforce strict constraints and perform optimisations, which is why the CSS is so much smaller and safer. Style conflicts and unbounded CSS growth are avoided.