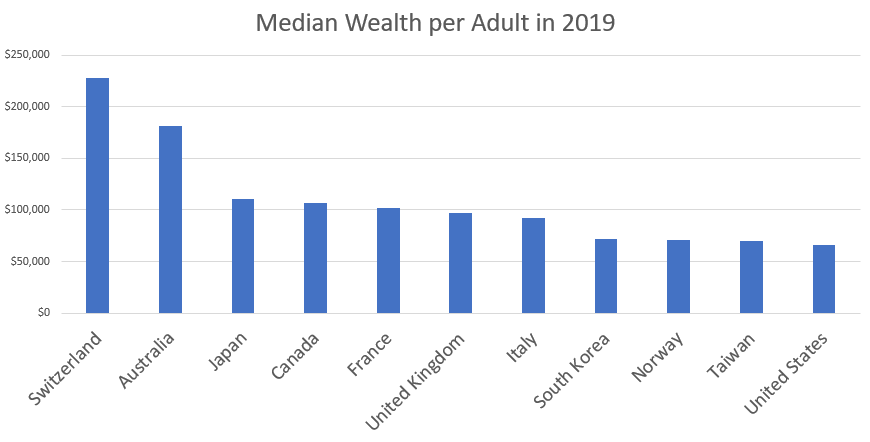

This is a fact that is not widely known or appreciated.

Yes, these numbers don't include things like Social Security, just privately held wealth. They're not an attempt to capitalize every possible future income stream.

— Noahtogolpe \U0001f407 (@Noahpinion) January 10, 2021

Imagine for a moment the most obscurantist, jargon-filled, po-mo article the politically correct academy might produce. Pure SJW nonsense. Got it? Chances are you're imagining something like the infamous "Feminist Glaciology" article from a few years back.https://t.co/NRaWNREBvR pic.twitter.com/qtSFBYY80S

— Jeffrey Sachs (@JeffreyASachs) October 13, 2018

Bloomberg Ideas conference now starting! I will be live-tweeting it. You can watch on our Facebook or Twitter pages (links below)! https://t.co/Mbr9dZzWBy

— Noah Smith (@Noahpinion) October 25, 2018

True State of the Nation

— Secret SoSHHiety (@SouledOutWorld) December 19, 2020

You think you know what's coming... but you don't...https://t.co/MVoIuxgaWX pic.twitter.com/DtF2Q53HrT

Truth About Antarctica

— Secret SoSHHiety (@SouledOutWorld) December 19, 2020

Why? Scalar EM Antennas are kept at Antarctica; Scalar EM weaponry is the anonymous weapon to be used by the White Horse of Rev 6.https://t.co/7CDzmQfLSX pic.twitter.com/0400oCN8io

The Finger (fuck you/fuck the world)

— Secret SoSHHiety (@SouledOutWorld) December 18, 2020

The middle finger is the Saturn finger.https://t.co/BsrsBE3f5h pic.twitter.com/ZJqZll8lU1

Bread and Circuses

— Secret SoSHHiety (@SouledOutWorld) December 18, 2020

Bring in the clowns & the fast food...https://t.co/SZAlfkqTI3 pic.twitter.com/gLys0mNMIq

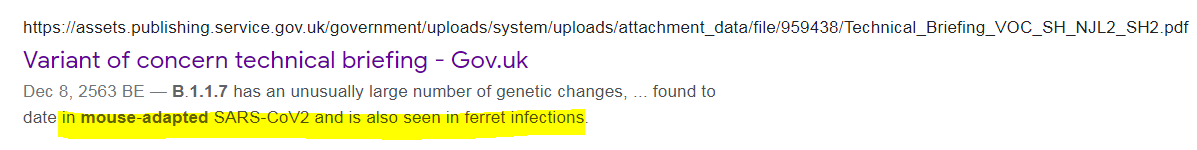

1. From Day 1, SARS-COV-2 was very well adapted to humans .....and transgenic hACE2 Mice

— Billy Bostickson \U0001f3f4\U0001f441&\U0001f441 \U0001f193 (@BillyBostickson) January 30, 2021

"we generated a mouse model expressing hACE2 by using CRISPR/Cas9 knockin technology. In comparison with wild-type C57BL/6 mice, both young & aged hACE2 mice sustained high viral loads... pic.twitter.com/j94XtSkscj

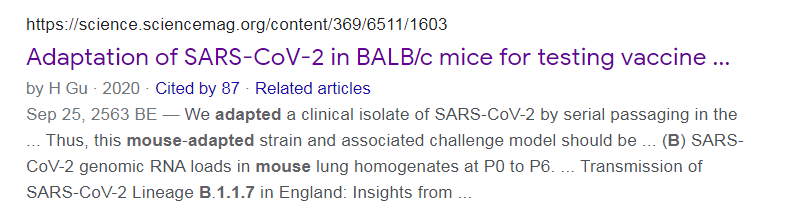

1. High Probability of serial passaging in Transgenic Mice expressing hACE2 in genesis of SARS-COV-2!

— Billy Bostickson \U0001f3f4\U0001f441&\U0001f441 \U0001f193 (@BillyBostickson) January 2, 2021

2 papers:

Human\u2013viral molecular mimicryhttps://t.co/irfH0Zgrve

Molecular Mimicryhttps://t.co/yLQoUtfS6s https://t.co/lsCv2iMEQz