After 4 years of Donald Trump, the US must "reassure" its allies.

That's what I'm reading/hearing lately, such as in this @nytimes piece. What do international relations scholars know about reassuring allies? Can it be done? Is it even

Indeed, such a tall order that it's been a major question explored by international relations scholars for a long time. A LONG TIME.

https://t.co/97fUw7sIj5

This included Robert Schelling's paper in the first issue of the Journal of Conflict Resolution...

https://t.co/rdd1N24HhZ

https://t.co/R9KgFmwOVB

The core difficulty with evaluating deterrence is "selection bias" and an inability to see the "counterfactual" (i.e. we only observe deterrence failures).

https://t.co/2uyzeGHQ15

7/ He does not think the "selection bias" can be dismissed and that accounting for it will have key implications for who we think about deterrence pic.twitter.com/YZriK5KH6B

— Paul Poast (@ProfPaulPoast) March 3, 2019

What the research finds is not supportive.

https://t.co/7jblEd27n8

https://t.co/EdweUhWHd0

https://t.co/2hBOdsNT3F

https://t.co/aHiQlpDWYj

What else can be done?

https://t.co/SGvUwGm8K4

https://t.co/ECh84QJ0Rv

https://t.co/abYBpwkuBp

https://t.co/KRA2wgHN4P

https://t.co/od5Aczh4GT

More from Paul Poast

Was the attack on the US Capitol an attempted coup?

Rather than debate that question here (or in another forum), I'm making it an assignment. Specifically, I'm asking my Quantitative Security students to determine if it belongs in our coup/attempted coup datasets.

[THREAD]

A core goal of this course is to introduce students to how Large-N data on violence and security are created.

We put WAY TOO much emphasis on estimators & software (Stata v R 🙄); not enough on the quality of the data going into the analysis.

First, what happened? @johncarey03755 offers a succinct

Second, I'll ask the students to read some of the recent pieces that say the event was NOT a coup attempt.

These include...

...detailed twitter threads by

Rather than debate that question here (or in another forum), I'm making it an assignment. Specifically, I'm asking my Quantitative Security students to determine if it belongs in our coup/attempted coup datasets.

[THREAD]

A core goal of this course is to introduce students to how Large-N data on violence and security are created.

We put WAY TOO much emphasis on estimators & software (Stata v R 🙄); not enough on the quality of the data going into the analysis.

First, what happened? @johncarey03755 offers a succinct

Second, I'll ask the students to read some of the recent pieces that say the event was NOT a coup attempt.

These include...

...detailed twitter threads by

Let me try this again\u2026 What would it look like if this were a coup (failed, in progress, or otherwise)? 1/n

— Kristen Harkness (@HarknessKristen) January 7, 2021

Why are civil-mil scholars upset about Austin Lloyd's nomination as the 28th Secretary of Defense?

Consider the nomination of the 3rd Secretary of Defense: George Marshall

[THREAD]

In 1950, Truman wanted to fire the second SecDef, Louis Johnson, and install George Marshall as Secretary of Defense.

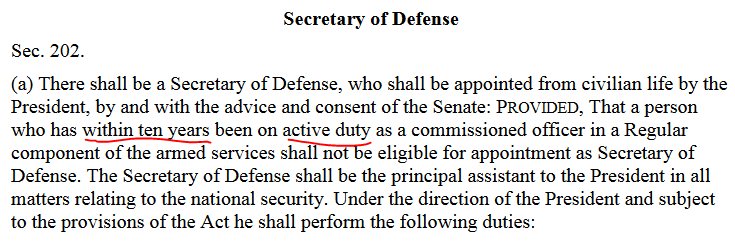

There was a problem: when the Department of Defense was created in 1947, section 202 of the 1947 National Security Act (which created the DoD, then called "The National Military Establishment") would not allow recently retired officers to serve as SecDef

https://t.co/bWx4h1OFah

Marshall had only retired as a 5-star General in 1947

Of course, by 1950 Marshall had already served as Secretary of State and had proposed the "Marshall Plan" for the recovery of Europe

Consider the nomination of the 3rd Secretary of Defense: George Marshall

[THREAD]

In 1950, Truman wanted to fire the second SecDef, Louis Johnson, and install George Marshall as Secretary of Defense.

There was a problem: when the Department of Defense was created in 1947, section 202 of the 1947 National Security Act (which created the DoD, then called "The National Military Establishment") would not allow recently retired officers to serve as SecDef

https://t.co/bWx4h1OFah

Marshall had only retired as a 5-star General in 1947

Of course, by 1950 Marshall had already served as Secretary of State and had proposed the "Marshall Plan" for the recovery of Europe

Is it true that democracies don't go to war with each other?

Sort of. But I wouldn't base public policy on the finding.

Why? Let's turn to the data.

[THREAD]

The idea of a "Democratic Peace" is a widely held view that's been around for a long time.

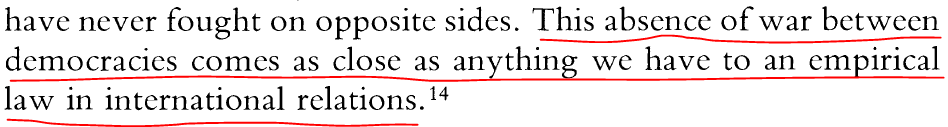

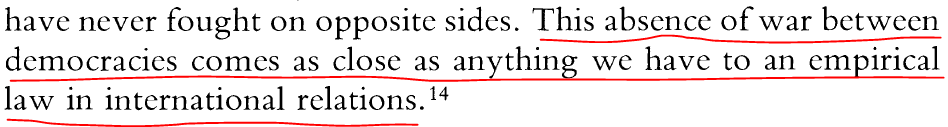

By 1988, there already existed enough studies on the topic for Jack Levy to famously label Democratic Peace "an empirical law"

The earliest empirical work on the topic was the 1964 report by Dean Babst published in the "Wisconsin Sociologist"

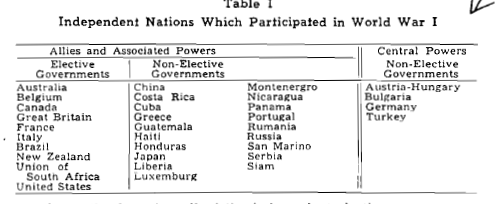

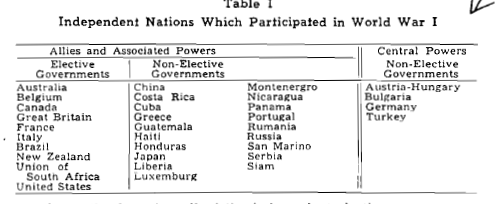

Using the war participation data from Quincy Wright's "A Study of War", Babst produced the following two tables

The tables show that democracies were NOT on both sides (of course, Finland is awkward given that it fought WITH Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union).

Babst expanded his study beyond the World Wars in a 1972 paper in Industrial Research. He confirmed his finding.

Sort of. But I wouldn't base public policy on the finding.

Why? Let's turn to the data.

[THREAD]

Democracies do not go to war with each other. There are a lot of empirical data to support that theory. I summarize that literature here. https://t.co/SQLk9J9rZ8 https://t.co/tLlSyisEIU

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) December 12, 2020

The idea of a "Democratic Peace" is a widely held view that's been around for a long time.

By 1988, there already existed enough studies on the topic for Jack Levy to famously label Democratic Peace "an empirical law"

The earliest empirical work on the topic was the 1964 report by Dean Babst published in the "Wisconsin Sociologist"

Using the war participation data from Quincy Wright's "A Study of War", Babst produced the following two tables

The tables show that democracies were NOT on both sides (of course, Finland is awkward given that it fought WITH Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union).

Babst expanded his study beyond the World Wars in a 1972 paper in Industrial Research. He confirmed his finding.

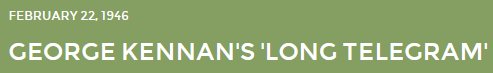

Let's talk about that "Longer Telegram" making the rounds...and why it's a

First, to be clear, it IS NOT a telegram. It's a report. I mean, it has a flipping 11.5 page executive "summary"...

...a two page table of contents...

...and clocks in at 62 pages (minus the forward and executive summary) or 73 pages (if you include the executive summary).

Of course, the author of "The Longer Telegram" calls it a "telegram" because they want it to be directly and explicitly compared to George Kennan's 1946 "Long Telegram" about US policy towards the Soviet Union.

https://t.co/rHikkOYuoT

First, to be clear, it IS NOT a telegram. It's a report. I mean, it has a flipping 11.5 page executive "summary"...

...a two page table of contents...

...and clocks in at 62 pages (minus the forward and executive summary) or 73 pages (if you include the executive summary).

Of course, the author of "The Longer Telegram" calls it a "telegram" because they want it to be directly and explicitly compared to George Kennan's 1946 "Long Telegram" about US policy towards the Soviet Union.

https://t.co/rHikkOYuoT