🧵 Two of my most- and first-used checks when doing a performance audit are surprisingly old school: 1) Validate HTML 2) Disable JS.

More from Tech

BREAKING: @CommonsCMS @DamianCollins just released previously sealed #Six4Three @Facebook documents:

Some random interesting tidbits:

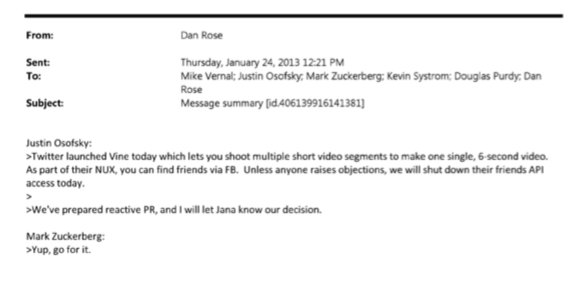

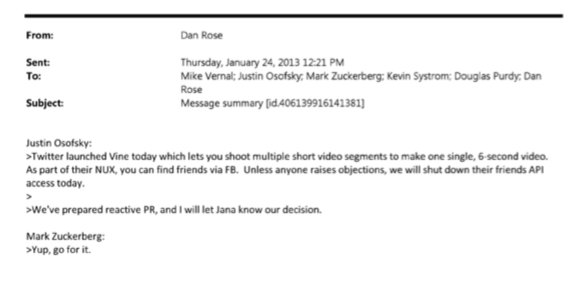

1) Zuck approves shutting down platform API access for Twitter's when Vine is released #competition

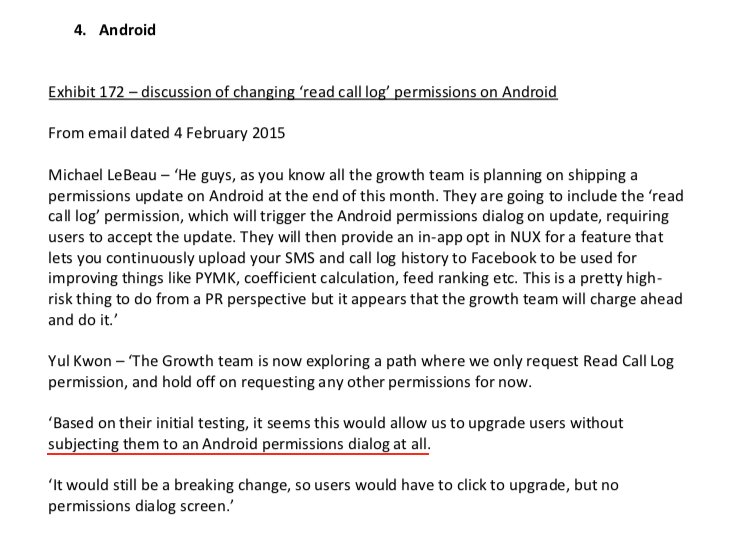

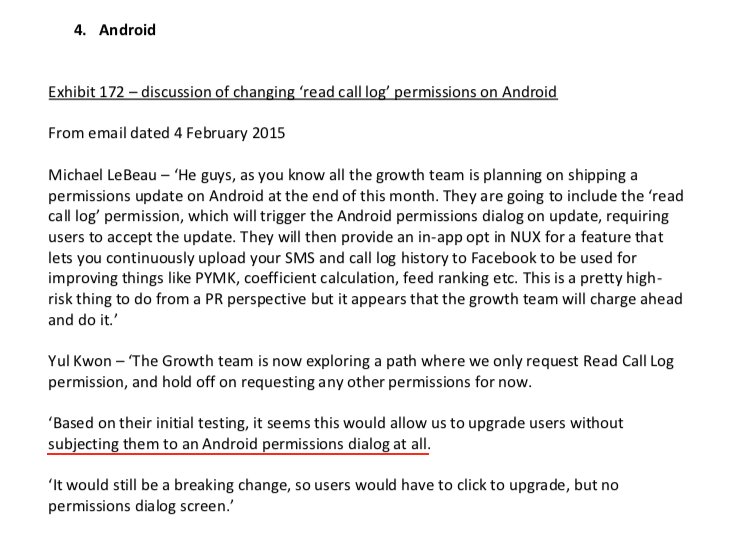

2) Facebook engineered ways to access user's call history w/o alerting users:

Team considered access to call history considered 'high PR risk' but 'growth team will charge ahead'. @Facebook created upgrade path to access data w/o subjecting users to Android permissions dialogue.

3) The above also confirms @kashhill and other's suspicion that call history was used to improve PYMK (People You May Know) suggestions and newsfeed rankings.

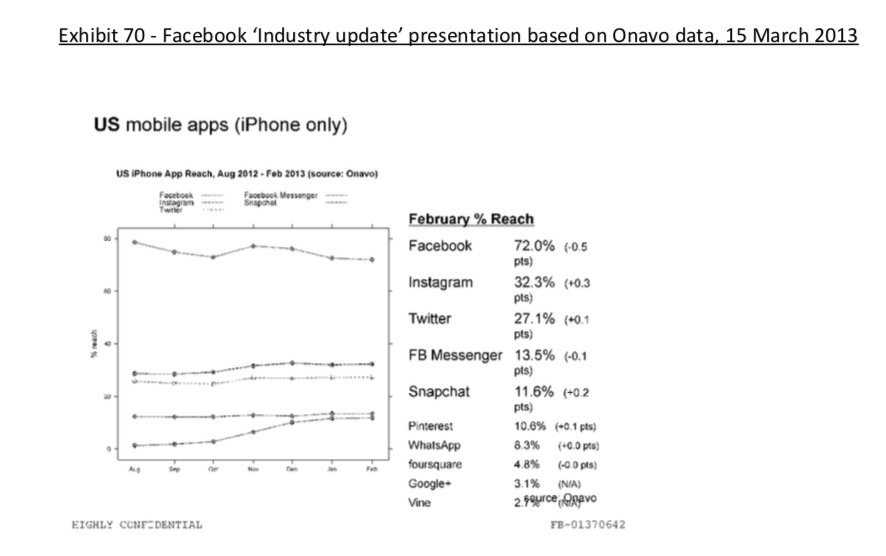

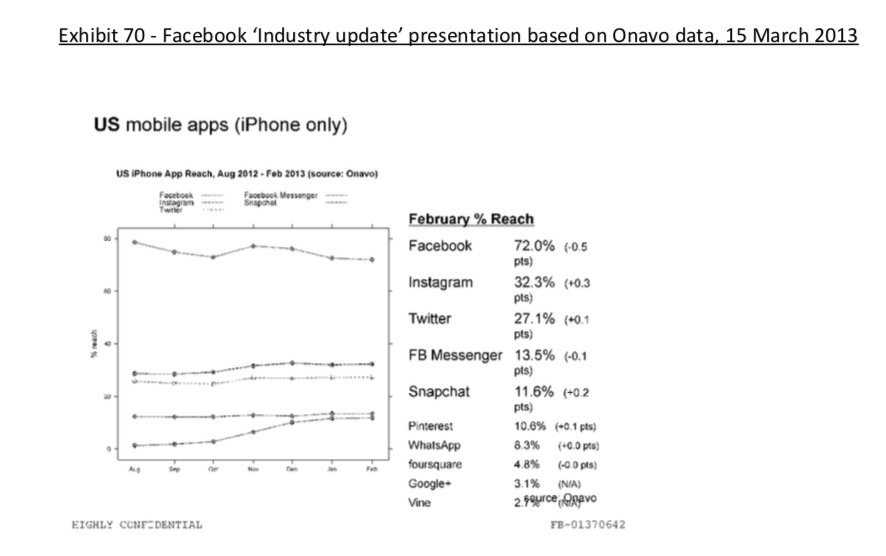

4) Docs also shed more light into @dseetharaman's story on @Facebook monitoring users' @Onavo VPN activity to determine what competitors to mimic or acquire in 2013.

https://t.co/PwiRIL3v9x

Some random interesting tidbits:

1) Zuck approves shutting down platform API access for Twitter's when Vine is released #competition

2) Facebook engineered ways to access user's call history w/o alerting users:

Team considered access to call history considered 'high PR risk' but 'growth team will charge ahead'. @Facebook created upgrade path to access data w/o subjecting users to Android permissions dialogue.

3) The above also confirms @kashhill and other's suspicion that call history was used to improve PYMK (People You May Know) suggestions and newsfeed rankings.

4) Docs also shed more light into @dseetharaman's story on @Facebook monitoring users' @Onavo VPN activity to determine what competitors to mimic or acquire in 2013.

https://t.co/PwiRIL3v9x

You May Also Like

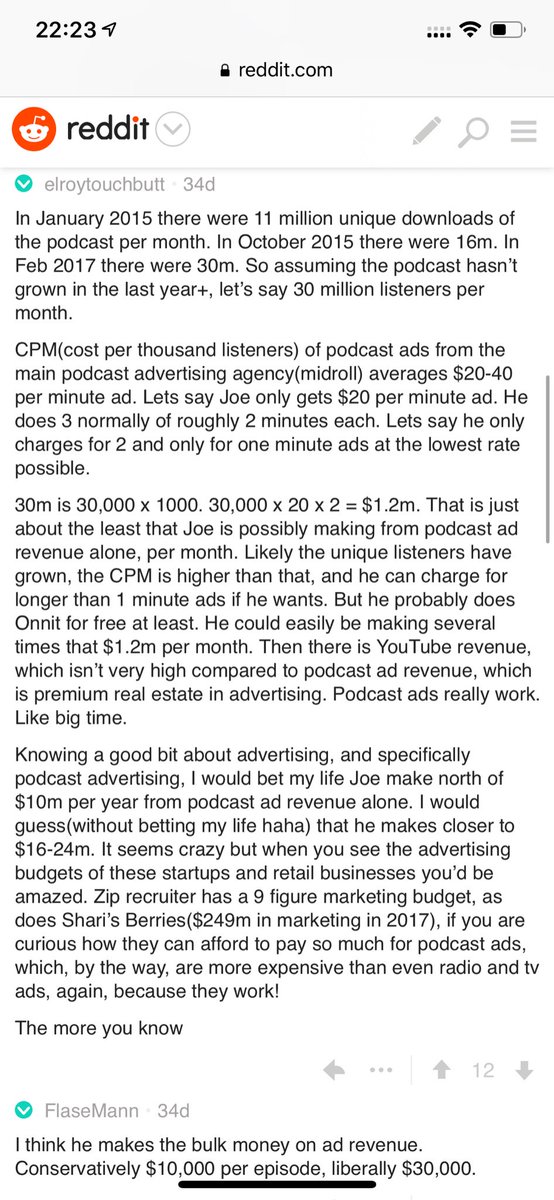

Joe Rogan's podcast is now is listened to 1.5+ billion times per year at around $50-100M/year revenue.

Independent and 100% owned by Joe, no networks, no middle men and a 100M+ people audience.

👏

https://t.co/RywAiBxA3s

Joe is the #1 / #2 podcast (depends per week) of all podcasts

120 million plays per month source https://t.co/k7L1LfDdcM

https://t.co/aGcYnVDpMu

Independent and 100% owned by Joe, no networks, no middle men and a 100M+ people audience.

👏

https://t.co/RywAiBxA3s

Joe is the #1 / #2 podcast (depends per week) of all podcasts

120 million plays per month source https://t.co/k7L1LfDdcM

https://t.co/aGcYnVDpMu