1/ Thread: "A Silicon Valley Ponzi Scheme"

Thanks to @chamath for laying this out in Social Capital's 2018 annual letter.

I've always appreciated his outspokenness.

This is creating a big bill that will soon come due...

But it's not who you think (that does), and the dynamics we’ve entered is in many ways creating a dangerous, high stakes Ponzi scheme.

Someone has to pay for the outrageous costs of this style of growth. Will it be VCs?

Likely not.

Eg: VCs habitually invest in one another’s companies during later rounds, bidding up rounds to valuations that allow for generous markups on their funds' performance.

if you’re a VC with a $200 million dollar fund, you’re able to draw $4million each year in fees.

Most funds never return enough profit for managers to see a dime of carried interest.

If u can show marked up paper returns & then parlay those returns into a newer, larger fund—say $500 million—you now have a fresh $10 million a year to use as you see fit.

There’s some deep misalignment here...

Partly why American healthcare is so expensive is bcos insurers, who play a key middleman role in setting prices for medical care, have a 2-sided biz model:

High costs allow them to charge higher premiums, allowing them to pull steadily more and more money out of patients’ and payers’ pockets.

In the end, both, patients and payers are the ones who end up as bag holders footing the bill.

The same thing is happening in today’s venture world.

Just as insurers’ biz model translates to higher costs of patient care,

So if its not VCs, who ends up holding the bag?

It’s still not who you’d expect.

In some cases, high prices may even work to their advantage.

Unlike the other pass-the-buck schemes

The real bill ends up getting shuffled outta sight to 2 other groups.

The 1st as u may guess are early stage funds’ limited partners, particularly future limited partners investing into the next fund.

Marking up Fund IV to raise money for more mgmt fees out of Fund V is so effective bcos fundraising can happen much faster than the long & difficult job of building businesses & creating real enterprise value

The second group of people left holding the bag is far more tragic: the employees at startups.

Although originally helpful as a way to incentivize and reward employees for working hard for an uncertain outcome,

Overall, you can understand how this arrangement endures:

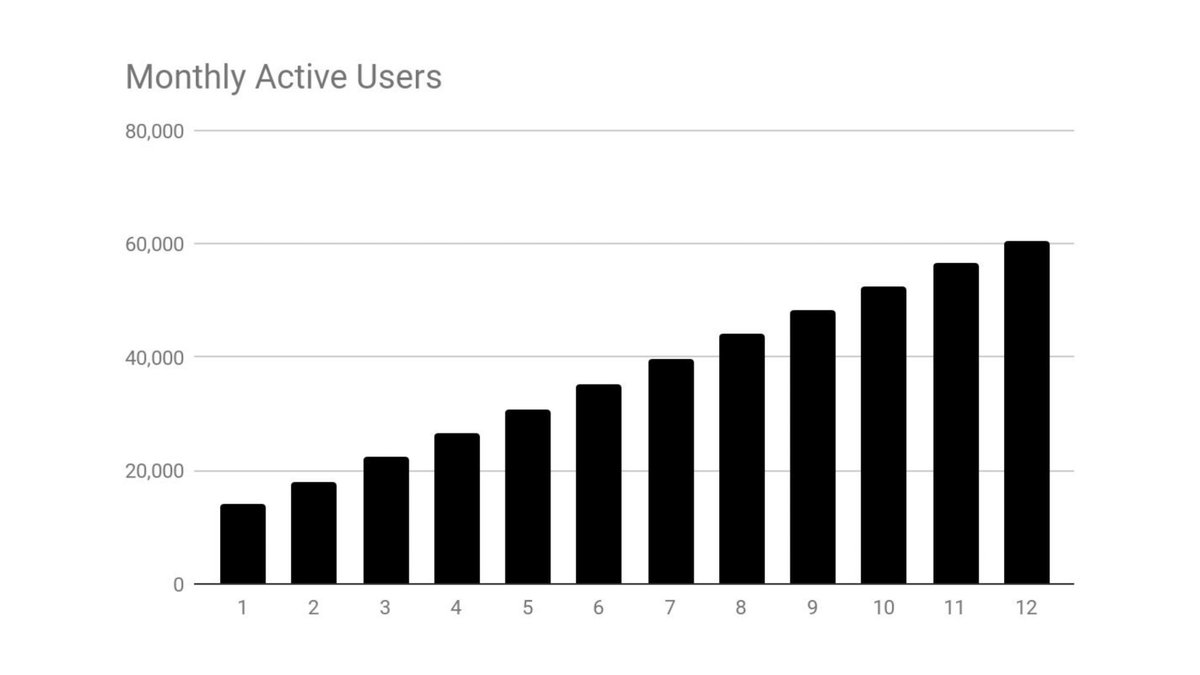

Those companies then go spend the money on more user growth, often in zero-sum competition w/ one another.

What is the antidote here? Its 2-fold.

The 2nd is to break away from the MLM scheme that the VC-LP-user growth game has become.

It’s time to wait patiently, as the air is slowly let out of this bizarre Ponzi balloon created by the venture capital industry.

More from Tech

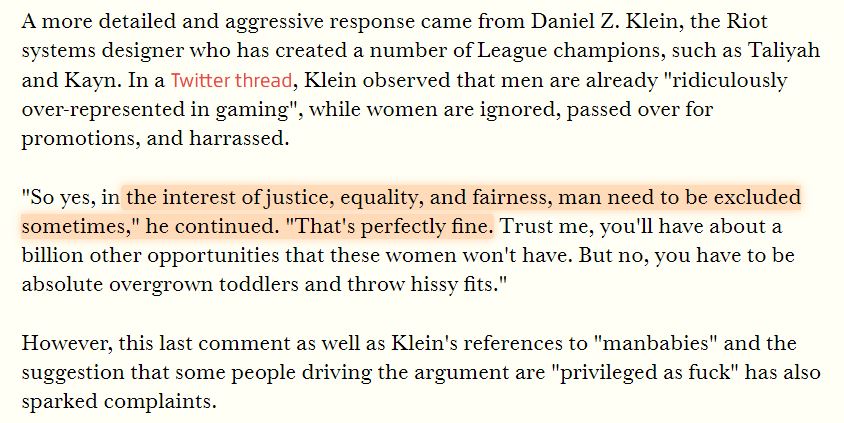

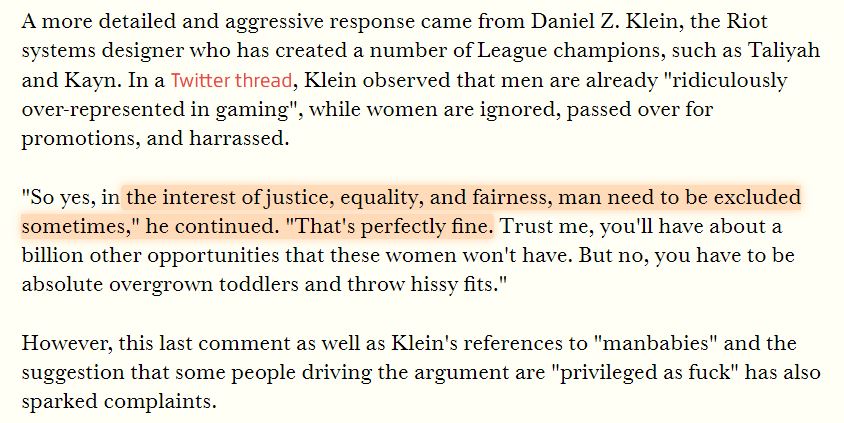

The first area to focus on is diversity. This has become a dogma in the tech world, and despite the fact that tech is one of the most meritocratic industries in the world, there are constant efforts to promote diversity at the expense of fairness, merit and competency. Examples:

USC's Interactive Media & Games Division cancels all-star panel that included top-tier game developers who were invited to share their experiences with students. Why? Because there were no women on the

ElectronConf is a conf which chooses presenters based on blind auditions; the identity, gender, and race of the speaker is not known to the selection team. The results of that merit-based approach was an all-male panel. So they cancelled the conference.

Apple's head of diversity (a black woman) got in trouble for promoting a vision of diversity that is at odds with contemporary progressive dogma. (She left the company shortly after this

Also in the name of diversity, there is unabashed discrimination against men (especially white men) in tech, in both hiring policies and in other arenas. One such example is this, a developer workshop that specifically excluded men: https://t.co/N0SkH4hR35

USC's Interactive Media & Games Division cancels all-star panel that included top-tier game developers who were invited to share their experiences with students. Why? Because there were no women on the

ElectronConf is a conf which chooses presenters based on blind auditions; the identity, gender, and race of the speaker is not known to the selection team. The results of that merit-based approach was an all-male panel. So they cancelled the conference.

Apple's head of diversity (a black woman) got in trouble for promoting a vision of diversity that is at odds with contemporary progressive dogma. (She left the company shortly after this

Also in the name of diversity, there is unabashed discrimination against men (especially white men) in tech, in both hiring policies and in other arenas. One such example is this, a developer workshop that specifically excluded men: https://t.co/N0SkH4hR35

The 12 most important pieces of information and concepts I wish I knew about equity, as a software engineer.

A thread.

1. Equity is something Big Tech and high-growth companies award to software engineers at all levels. The more senior you are, the bigger the ratio can be:

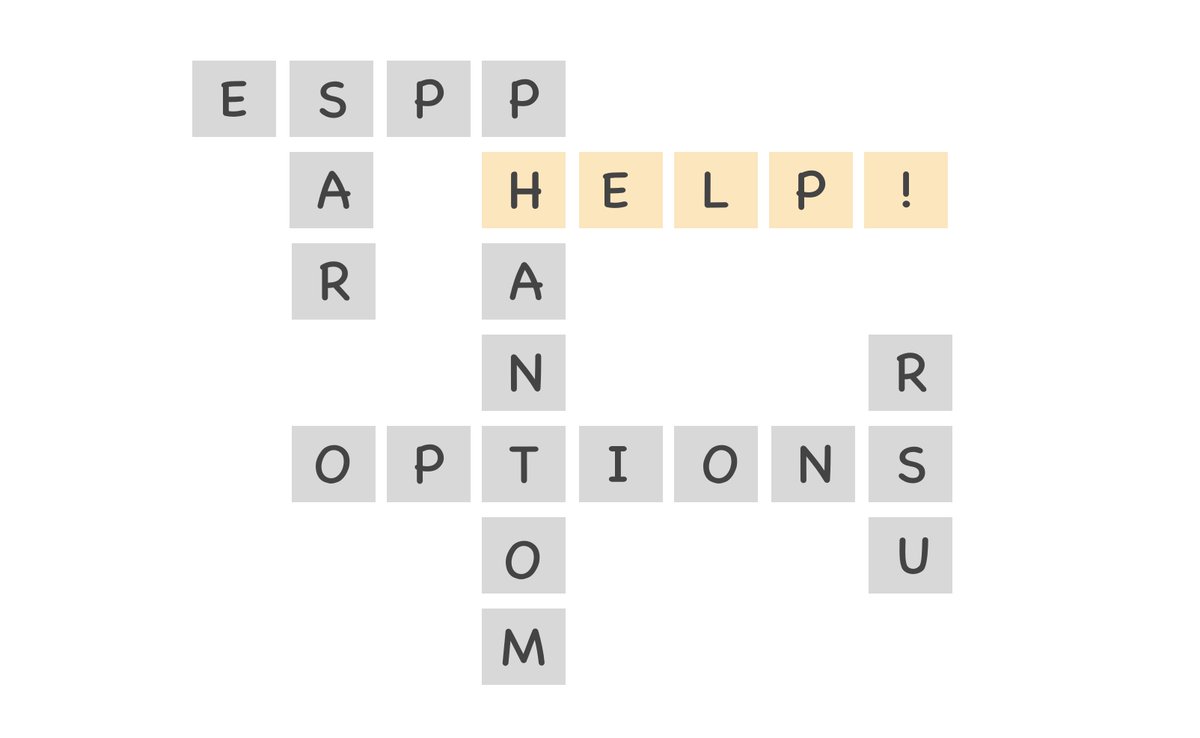

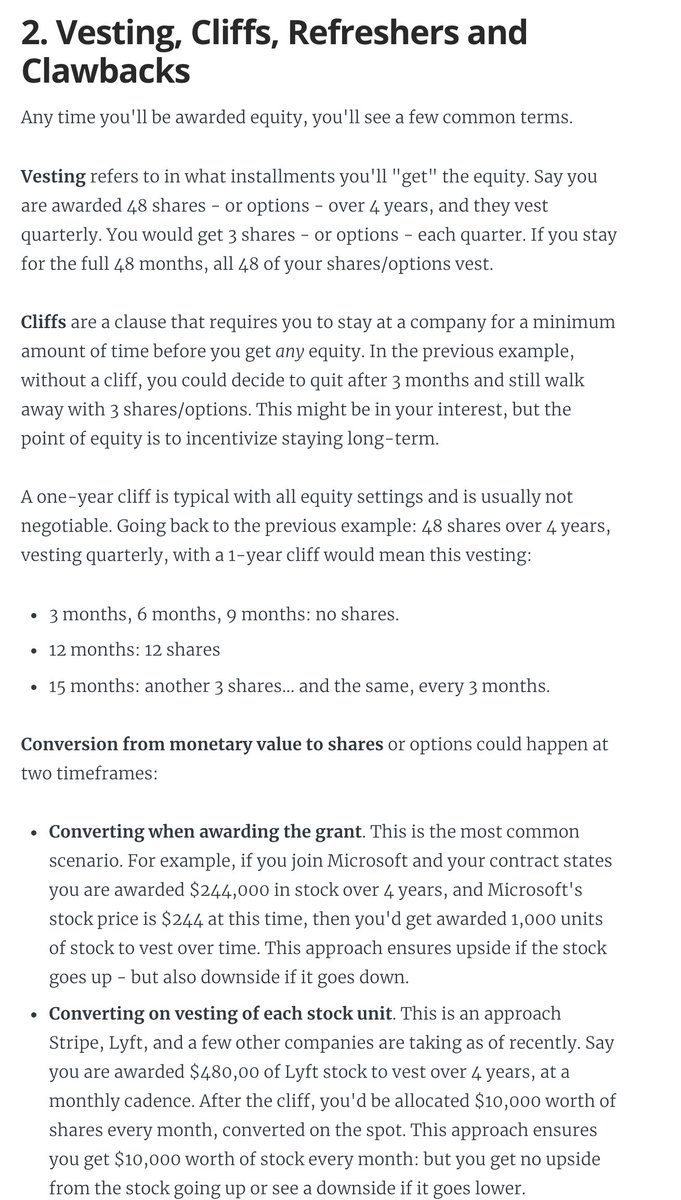

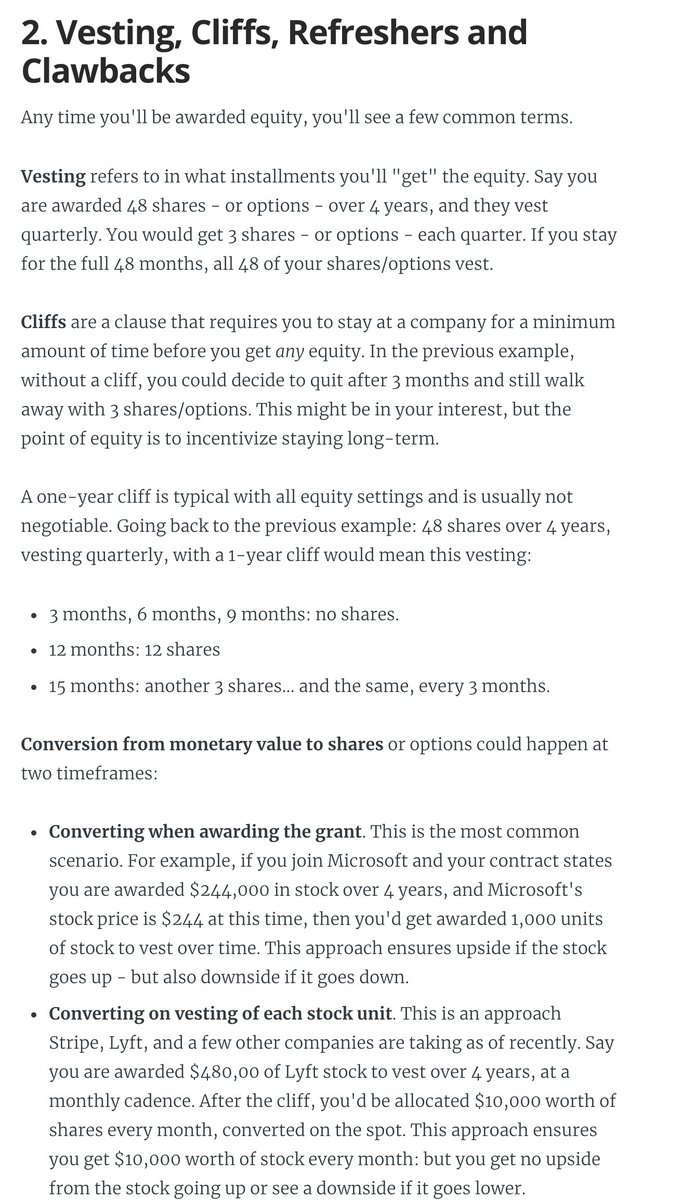

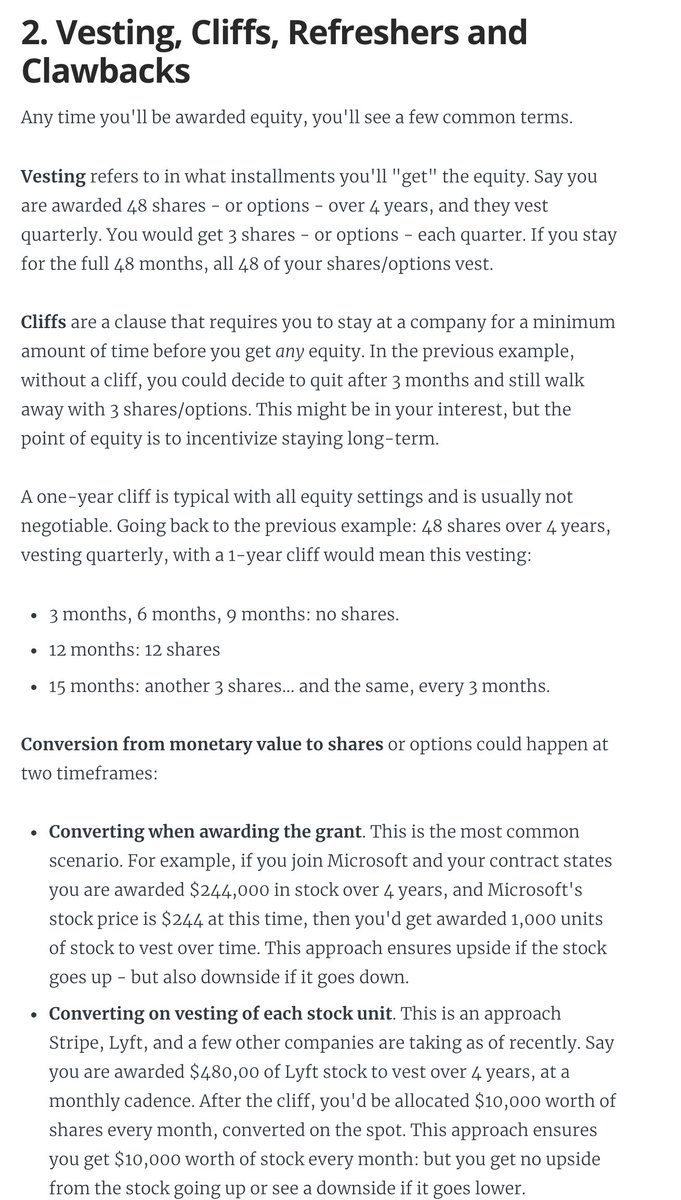

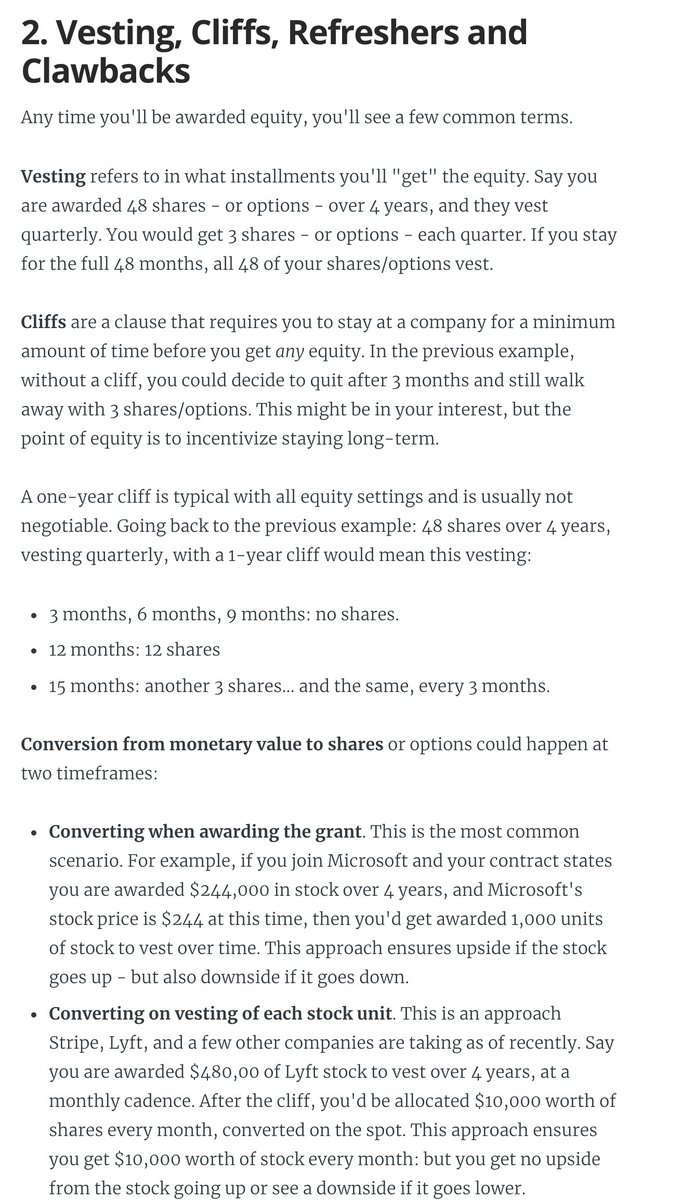

2. Vesting, cliffs, refreshers, and sign-on clawbacks.

If you get awarded equity, you'll want to understand vesting and cliffs. A 1-year cliff is pretty common in most places that award equity.

Read more in this blog post I wrote: https://t.co/WxQ9pQh2mY

3. Stock options / ESOPs.

The most common form of equity compensation at early-stage startups that are high-growth.

And there are *so* many pitfalls you'll want to be aware of. You need to do your research on this: I can't do justice in a tweet.

https://t.co/cudLn3ngqi

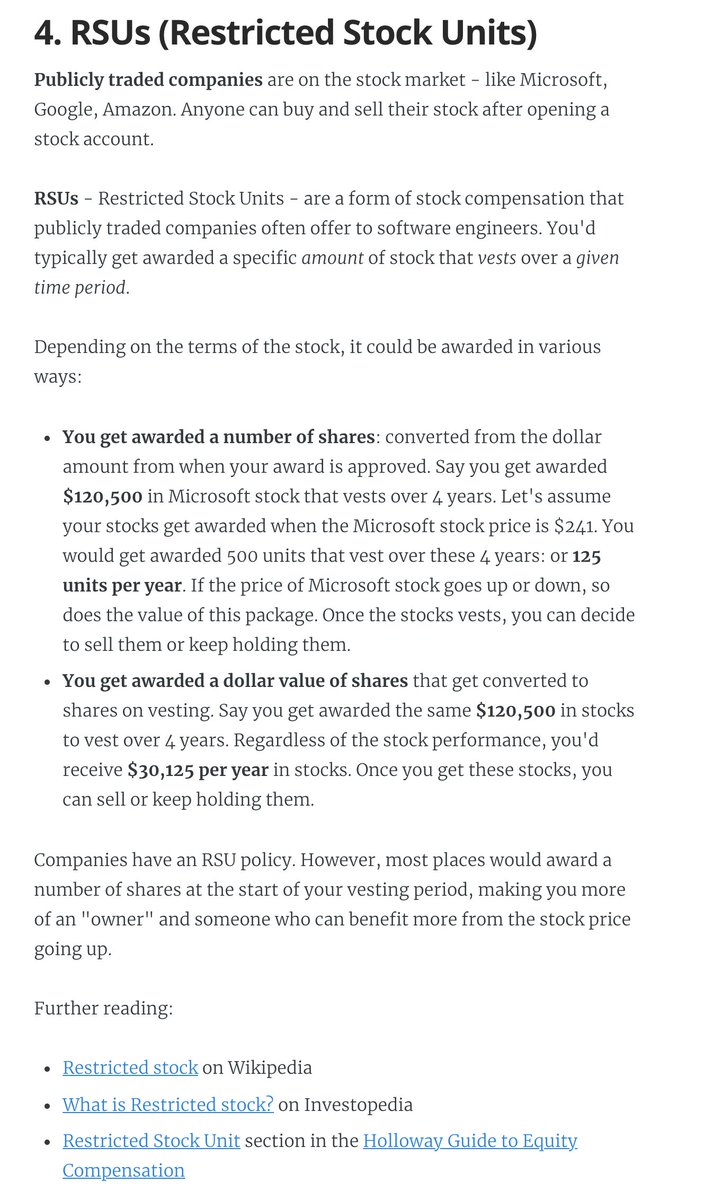

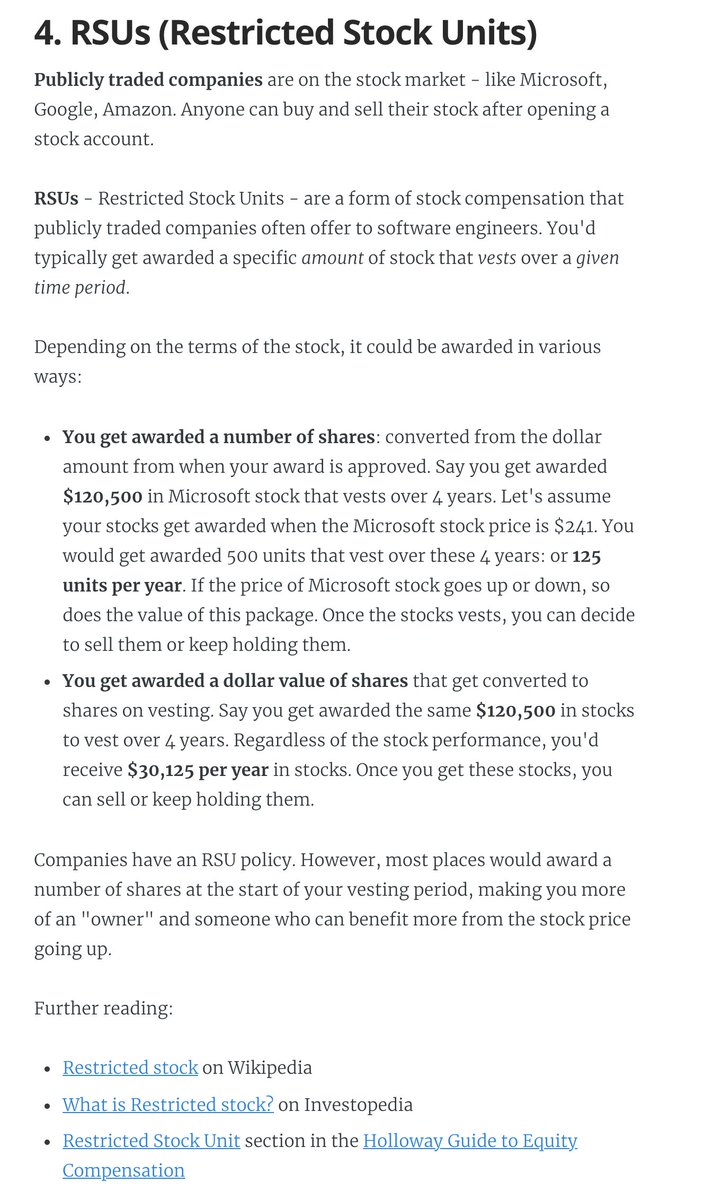

4. RSUs (Restricted Stock Units)

A common form of equity compensation for publicly traded companies and Big Tech. One of the easier types of equity to understand: https://t.co/a5xU1H9IHP

5. Double-trigger RSUs. Typically RSUs for pre-IPO companies. I got these at Uber.

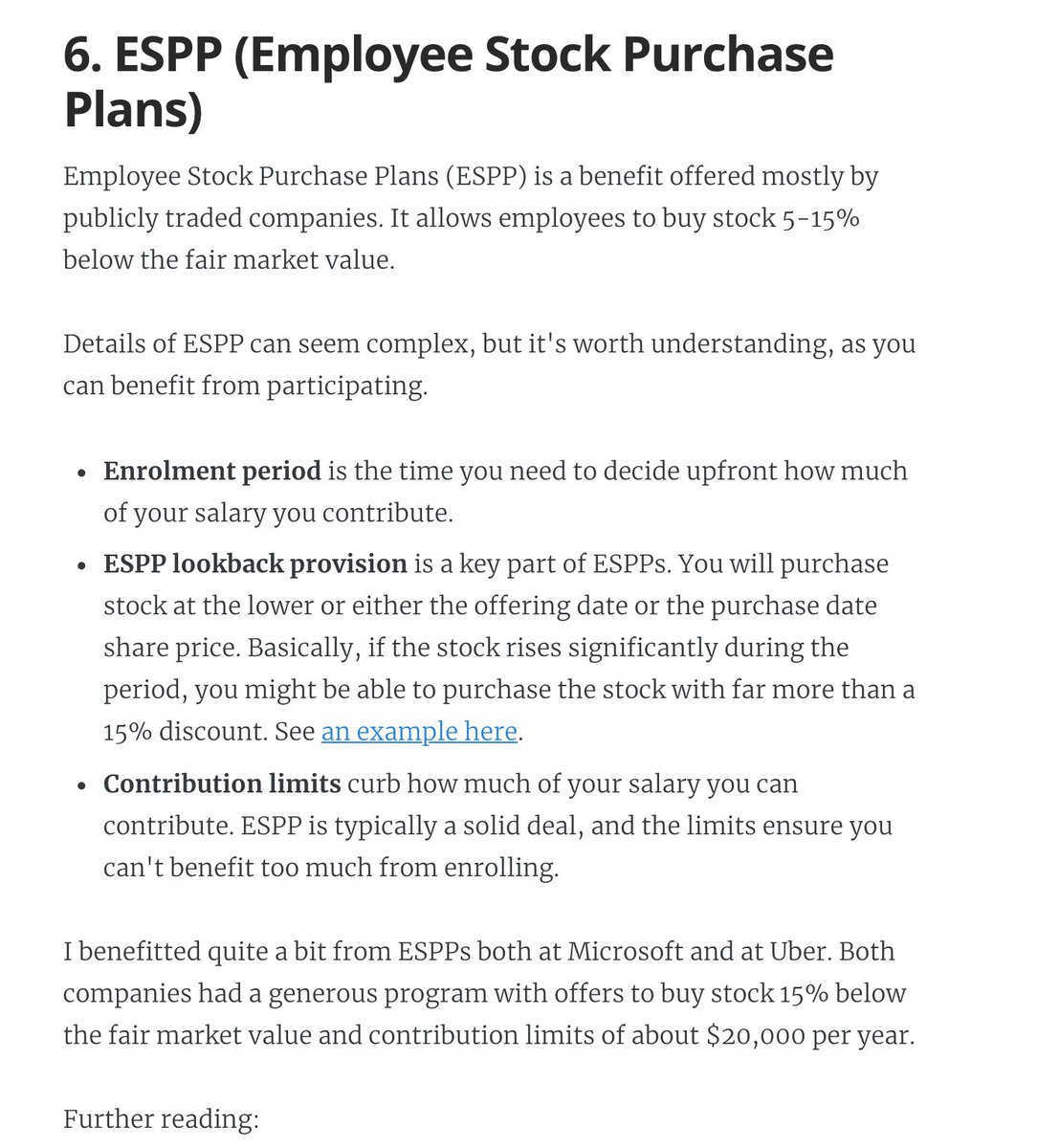

6. ESPP: a (typically) amazing employee perk at publicly traded companies. There's always risk, but this plan can typically offer good upsides.

7. Phantom shares. An interesting setup similar to RSUs... but you don't own stocks. Not frequent, but e.g. Adyen goes with this plan.

A thread.

1. Equity is something Big Tech and high-growth companies award to software engineers at all levels. The more senior you are, the bigger the ratio can be:

2. Vesting, cliffs, refreshers, and sign-on clawbacks.

If you get awarded equity, you'll want to understand vesting and cliffs. A 1-year cliff is pretty common in most places that award equity.

Read more in this blog post I wrote: https://t.co/WxQ9pQh2mY

3. Stock options / ESOPs.

The most common form of equity compensation at early-stage startups that are high-growth.

And there are *so* many pitfalls you'll want to be aware of. You need to do your research on this: I can't do justice in a tweet.

https://t.co/cudLn3ngqi

4. RSUs (Restricted Stock Units)

A common form of equity compensation for publicly traded companies and Big Tech. One of the easier types of equity to understand: https://t.co/a5xU1H9IHP

5. Double-trigger RSUs. Typically RSUs for pre-IPO companies. I got these at Uber.

6. ESPP: a (typically) amazing employee perk at publicly traded companies. There's always risk, but this plan can typically offer good upsides.

7. Phantom shares. An interesting setup similar to RSUs... but you don't own stocks. Not frequent, but e.g. Adyen goes with this plan.

You May Also Like

THE MEANING, SIGNIFICANCE AND HISTORY OF SWASTIK

The Swastik is a geometrical figure and an ancient religious icon. Swastik has been Sanatan Dharma’s symbol of auspiciousness – mangalya since time immemorial.

The name swastika comes from Sanskrit (Devanagari: स्वस्तिक, pronounced: swastik) &denotes “conducive to wellbeing or auspicious”.

The word Swastik has a definite etymological origin in Sanskrit. It is derived from the roots su – meaning “well or auspicious” & as meaning “being”.

"सु अस्ति येन तत स्वस्तिकं"

Swastik is de symbol through which everything auspicios occurs

Scholars believe word’s origin in Vedas,known as Swasti mantra;

"🕉स्वस्ति ना इन्द्रो वृधश्रवाहा

स्वस्ति ना पूषा विश्ववेदाहा

स्वस्तिनास्तरक्ष्यो अरिश्तनेमिही

स्वस्तिनो बृहस्पतिर्दधातु"

It translates to," O famed Indra, redeem us. O Pusha, the beholder of all knowledge, redeem us. Redeem us O Garudji, of limitless speed and O Bruhaspati, redeem us".

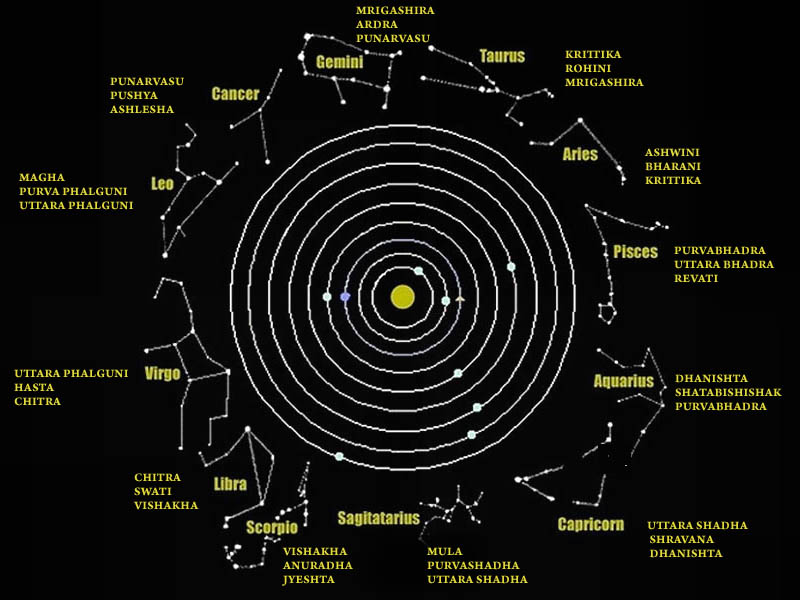

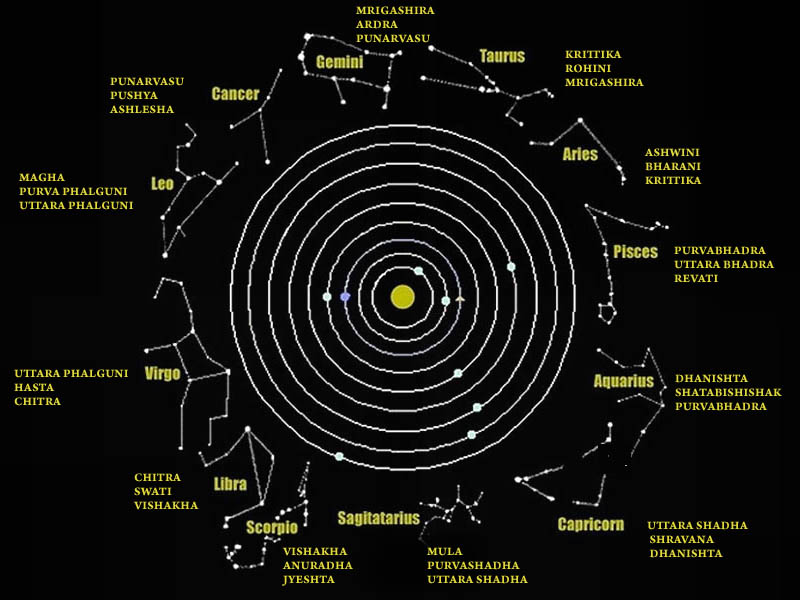

SWASTIK’s COSMIC ORIGIN

The Swastika represents the living creation in the whole Cosmos.

Hindu astronomers divide the ecliptic circle of cosmos in 27 divisions called https://t.co/sLeuV1R2eQ this manner a cross forms in 4 directions in the celestial sky. At centre of this cross is Dhruva(Polestar). In a line from Dhruva, the stars known as Saptarishi can be observed.

The Swastik is a geometrical figure and an ancient religious icon. Swastik has been Sanatan Dharma’s symbol of auspiciousness – mangalya since time immemorial.

The name swastika comes from Sanskrit (Devanagari: स्वस्तिक, pronounced: swastik) &denotes “conducive to wellbeing or auspicious”.

The word Swastik has a definite etymological origin in Sanskrit. It is derived from the roots su – meaning “well or auspicious” & as meaning “being”.

"सु अस्ति येन तत स्वस्तिकं"

Swastik is de symbol through which everything auspicios occurs

Scholars believe word’s origin in Vedas,known as Swasti mantra;

"🕉स्वस्ति ना इन्द्रो वृधश्रवाहा

स्वस्ति ना पूषा विश्ववेदाहा

स्वस्तिनास्तरक्ष्यो अरिश्तनेमिही

स्वस्तिनो बृहस्पतिर्दधातु"

It translates to," O famed Indra, redeem us. O Pusha, the beholder of all knowledge, redeem us. Redeem us O Garudji, of limitless speed and O Bruhaspati, redeem us".

SWASTIK’s COSMIC ORIGIN

The Swastika represents the living creation in the whole Cosmos.

Hindu astronomers divide the ecliptic circle of cosmos in 27 divisions called https://t.co/sLeuV1R2eQ this manner a cross forms in 4 directions in the celestial sky. At centre of this cross is Dhruva(Polestar). In a line from Dhruva, the stars known as Saptarishi can be observed.