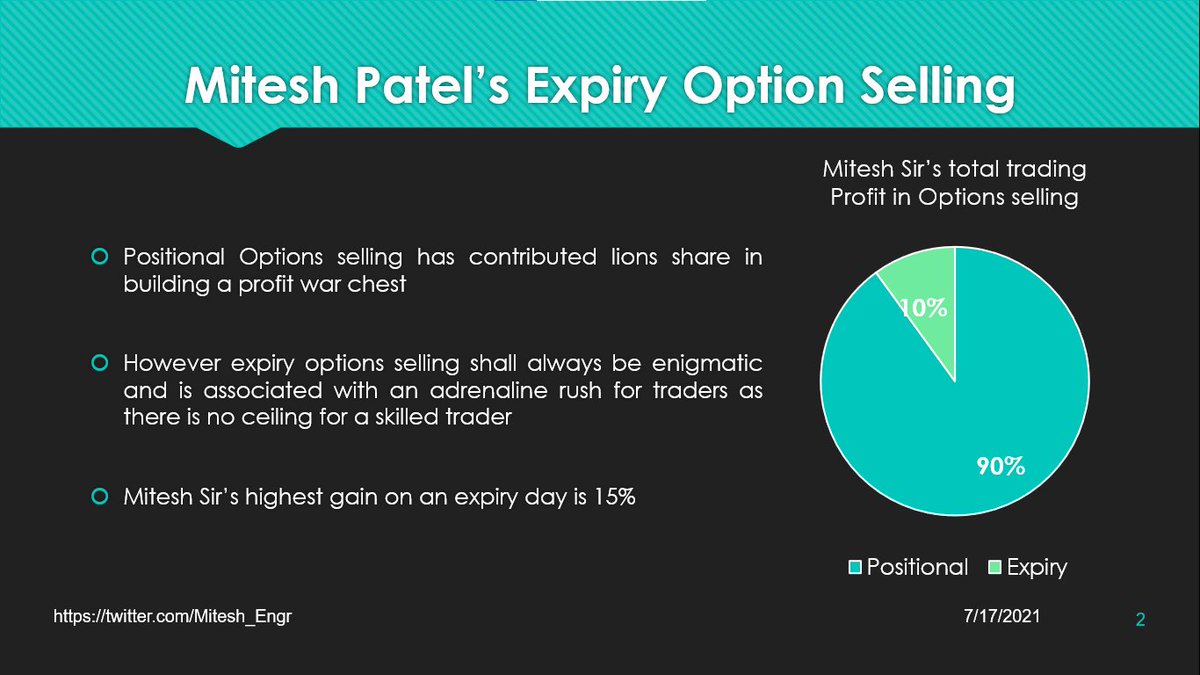

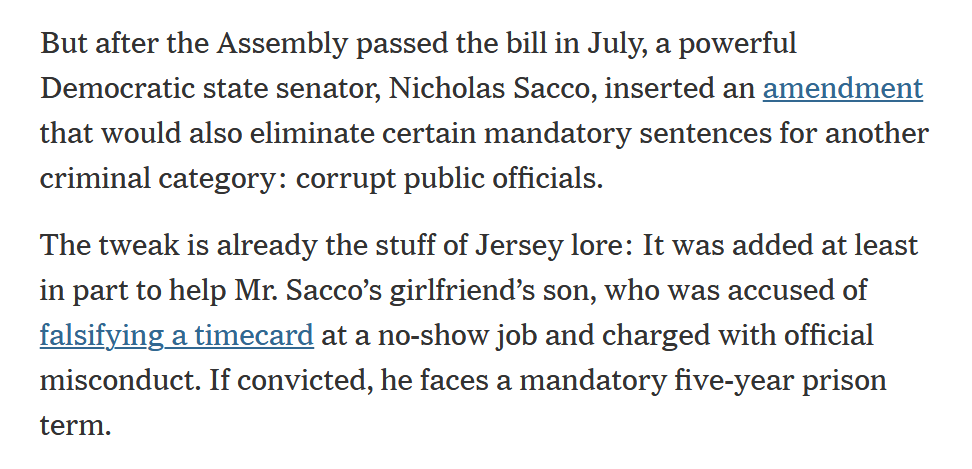

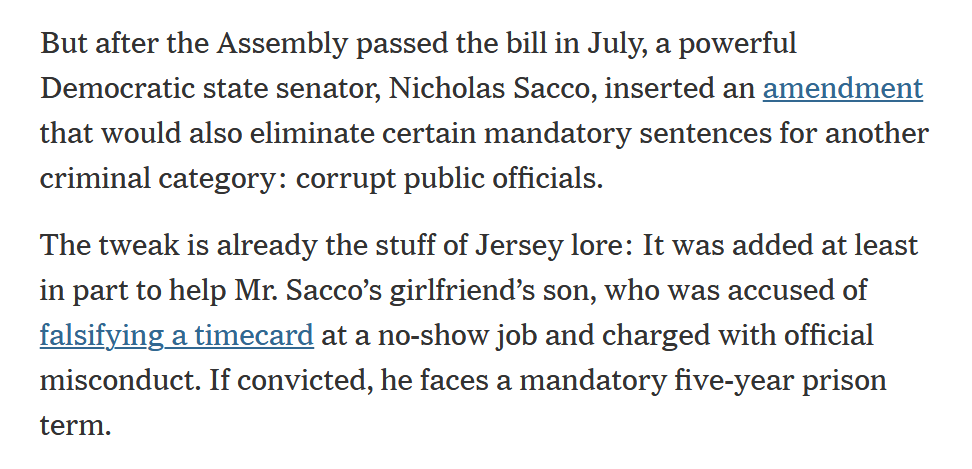

Let’s talk about this story. It discusses a NJ bill that is designed to make sentencing less harsh. The bill is being held up because a lawmaker introduced an amendment that would eliminate the mandatory minimum for one type of corruption.

We've seen the story before, and it sends us a different message.

The "I only realized when" framing tells us that we aren't paying enough attention to harshness & more reform is probably needed.

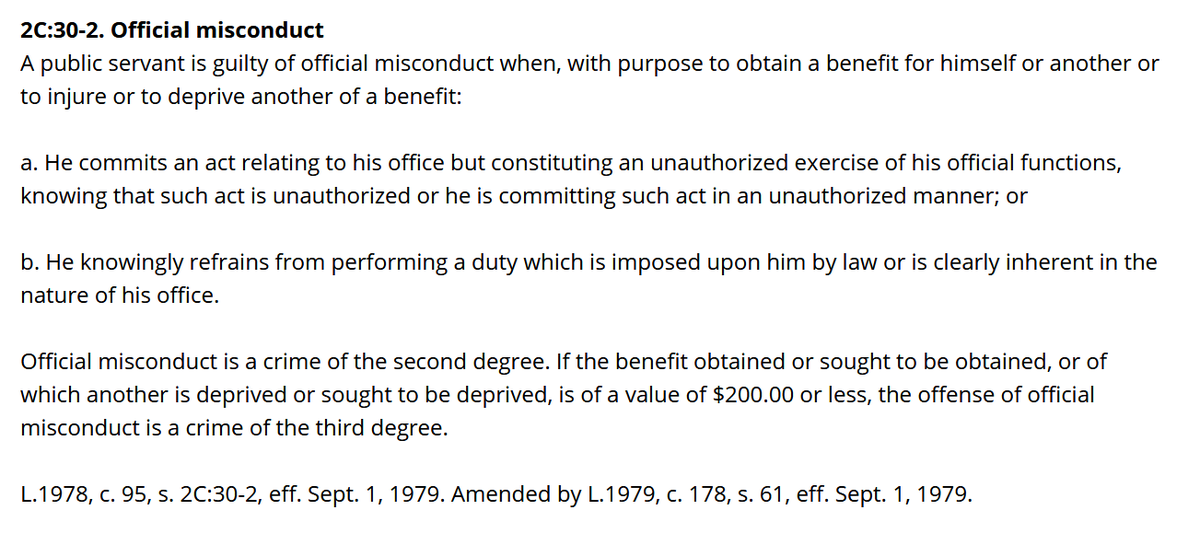

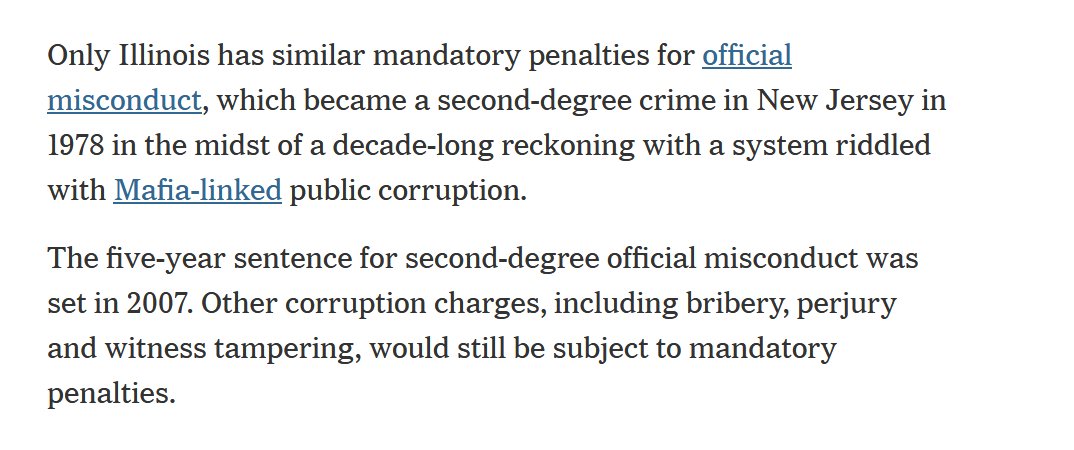

As someone who researches the statutory language of criminal laws, this law makes me very uncomfortable. The conduct is not well defined--look at that "clearly inherent" language. Yikes!

And if we are going to have a relatively vague law, do we want it to carry a 5 year mandatory sentence?

If the implication is supposed to be that judges as appointees can't be trusted, I wish it had mentioned that NJ prosecutors are selected the same way

The article never mentions that mandatory minimums are about shifting power over punishment decisions from judges to prosecutors.

But that's exactly what they do.

The argument is deterrence. If you know crime X carries Y mandatory minimum, then you are less likely to commit crime X.

The truth is that human beings don't really think like this. And the idea that people will be less likely to commit crimes because of higher punishments has been debunked lots of times.

Those people get it--mandatory minimums are not a good idea, even if you really don't like a particular type of crime.

But the idea that removing a mandatory minimum sentence sends the message that a crime is "tolerated" is just silly.

These groups should know better.

This desire for harshness is so prevalent, that some have coined the term "carceral progressivism"

One of the most consequential enforcement decisions is where to look for law breaking.

— Carissa Byrne Hessick (@CBHessick) September 28, 2020

And a policy of prioritizing low level enforcement over high level enforcement is impossible to defend on the merits. https://t.co/ZBNZoUudZF

More from Law

The entire first part of the hearing related to messages sent by certain individuals from the Stonewall Trans Advisory Group seeking cooperation with trans allies at Garden Court. So far all the discussion has been about whether their names must remain redacted.

— LGB Alliance (@ALLIANCELGB) February 11, 2021

The judge has ruled that for this hearing only, the names should remain redacted.

It is a Rule 50 Order. These particular individuals are members of Stonewall’s Trans Advisory Group and their names may well be known elsewhere. What is relevant is the messages from the group to Garden Court.

The judge states she would not make the same decision at the full hearing. This is only for the preliminary hearing.

Having dealt with the anonymity issue we now move to the main submissions in the case.

No matter how this trial plays out, the US will remain divided between those who choose truth, Democracy, and rule of law and the millions who reject these things.

1/

Wouldn't he just use this to repeat his Big Lie and have GOP echo him?

— Thel Marquez (@theljava) January 31, 2021

The question is how to move forward.

My mantra is that there are no magic bullets and these people will always be with us.

Except for state legislatures, they have less power now than they have for a while.

2/

The only real and lasting solutions are political ones. Get Democrats into local offices. Get people who want democracy to survive to the polls at every election, at every level.

It’s a constant battle.

3/

Maybe I should tell you all about Thurgood Marshall’s life to illustrate how hard the task is and how there will be backlash after each step of progress.

4/

Precisely. That's why Thurgood Marshall's life came to mind.

We are still riding the backlash that started after the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

That's why I keep saying there are no easy

Yep. My relatives continue to support Trump and make false equivalencies as justification. I\u2019ve found it impossible to present factual information that changes minds. Trump\u2019s emotional appeal registers with them: that things were better before civil rights advances.

— Martha Brockenbrough INTO THE BLOODRED WOODS (@mbrockenbrough) January 31, 2021