New NHS reforms announced today. Seems to be a story of two parts, plus a missing character. Quick thoughts (1/):

https://t.co/GChxwuvEF4

https://t.co/0tYunQaWkz

https://t.co/bMB9vvZm8t

(12/12) @HealthFdn

More from Health

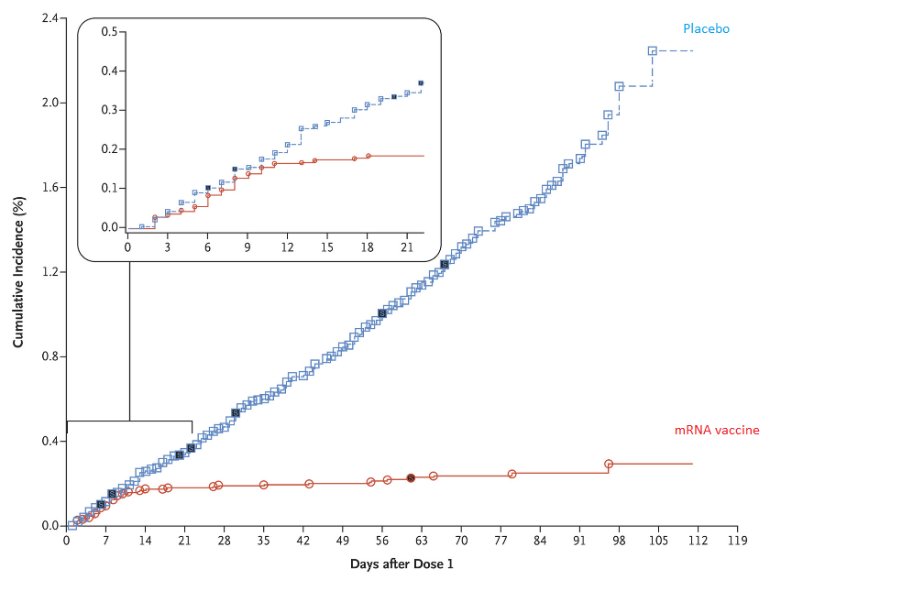

This is a limited point about availability of efficacy data for vaccines under development in the context of the approval for CovidShield and Covaxin in India.

There have been many so-called experts on the idiotbox opining about apparent availability of P III data which 1/n

2/n apparently the SEC had access to based on which it "supposedly" approved Covaxin. Another argument that is prevalent is other regulators (US FDA and MHRA) also approved vaccines based on P II data alone. Let me give you a few facts so that you can make your own decision.

3/n The protocols for both mRNA vaccines are publicly available. You can check. Both protocols *define* when the interim analysis will be done. This is not subjective. They clearly define how many infections need to be documented before the Data Safety Monitoring Board meets.

4/n Find the protocols for the bridging study for CovidShield and Covaxin and look for a similar milestone.

Here is one set of efficacy data post the interim analysis of a mRNA vaccine.

Source: https://t.co/BAPnP3PxEb

5/n This data was analyzed post the interim analysis where the blind was broken by the DSMB. Now ask yourself this question:

How does the SEC, or the sponsor of these studies, or the experts who are offering their opinion liberally on the idiotbox know what the efficacy is

There have been many so-called experts on the idiotbox opining about apparent availability of P III data which 1/n

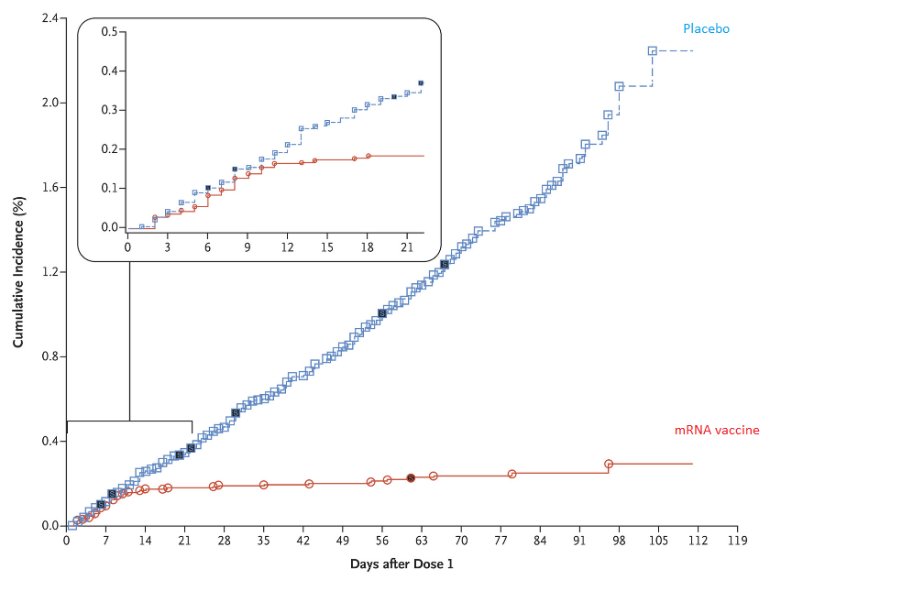

2/n apparently the SEC had access to based on which it "supposedly" approved Covaxin. Another argument that is prevalent is other regulators (US FDA and MHRA) also approved vaccines based on P II data alone. Let me give you a few facts so that you can make your own decision.

3/n The protocols for both mRNA vaccines are publicly available. You can check. Both protocols *define* when the interim analysis will be done. This is not subjective. They clearly define how many infections need to be documented before the Data Safety Monitoring Board meets.

4/n Find the protocols for the bridging study for CovidShield and Covaxin and look for a similar milestone.

Here is one set of efficacy data post the interim analysis of a mRNA vaccine.

Source: https://t.co/BAPnP3PxEb

5/n This data was analyzed post the interim analysis where the blind was broken by the DSMB. Now ask yourself this question:

How does the SEC, or the sponsor of these studies, or the experts who are offering their opinion liberally on the idiotbox know what the efficacy is

You May Also Like

I’m torn on how to approach the idea of luck. I’m the first to admit that I am one of the luckiest people on the planet. To be born into a prosperous American family in 1960 with smart parents is to start life on third base. The odds against my very existence are astronomical.

I’ve always felt that the luckiest people I know had a talent for recognizing circumstances, not of their own making, that were conducive to a favorable outcome and their ability to quickly take advantage of them.

In other words, dumb luck was just that, it required no awareness on the person’s part, whereas “smart” luck involved awareness followed by action before the circumstances changed.

So, was I “lucky” to be born when I was—nothing I had any control over—and that I came of age just as huge databases and computers were advancing to the point where I could use those tools to write “What Works on Wall Street?” Absolutely.

Was I lucky to start my stock market investments near the peak of interest rates which allowed me to spend the majority of my adult life in a falling rate environment? Yup.

Ironies of Luck https://t.co/5BPWGbAxFi

— Morgan Housel (@morganhousel) March 14, 2018

"Luck is the flip side of risk. They are mirrored cousins, driven by the same thing: You are one person in a 7 billion player game, and the accidental impact of other people\u2019s actions can be more consequential than your own."

I’ve always felt that the luckiest people I know had a talent for recognizing circumstances, not of their own making, that were conducive to a favorable outcome and their ability to quickly take advantage of them.

In other words, dumb luck was just that, it required no awareness on the person’s part, whereas “smart” luck involved awareness followed by action before the circumstances changed.

So, was I “lucky” to be born when I was—nothing I had any control over—and that I came of age just as huge databases and computers were advancing to the point where I could use those tools to write “What Works on Wall Street?” Absolutely.

Was I lucky to start my stock market investments near the peak of interest rates which allowed me to spend the majority of my adult life in a falling rate environment? Yup.