2/13

** MMT is the new supply-side economics

Forty years ago, some economists started from an uncontroversial (but important) result: a lower tax rate raises the tax base, so revenues won't fall as much. But then they ran with it, predicting tax rate cuts could raise revenues.

1/13

2/13

3/13

4/13

5/13

6/13

https://t.co/HkeNSN1FnU

7/13

8/13

https://t.co/orz7NTIg00

9/13

10/13

11/13

More from Economy

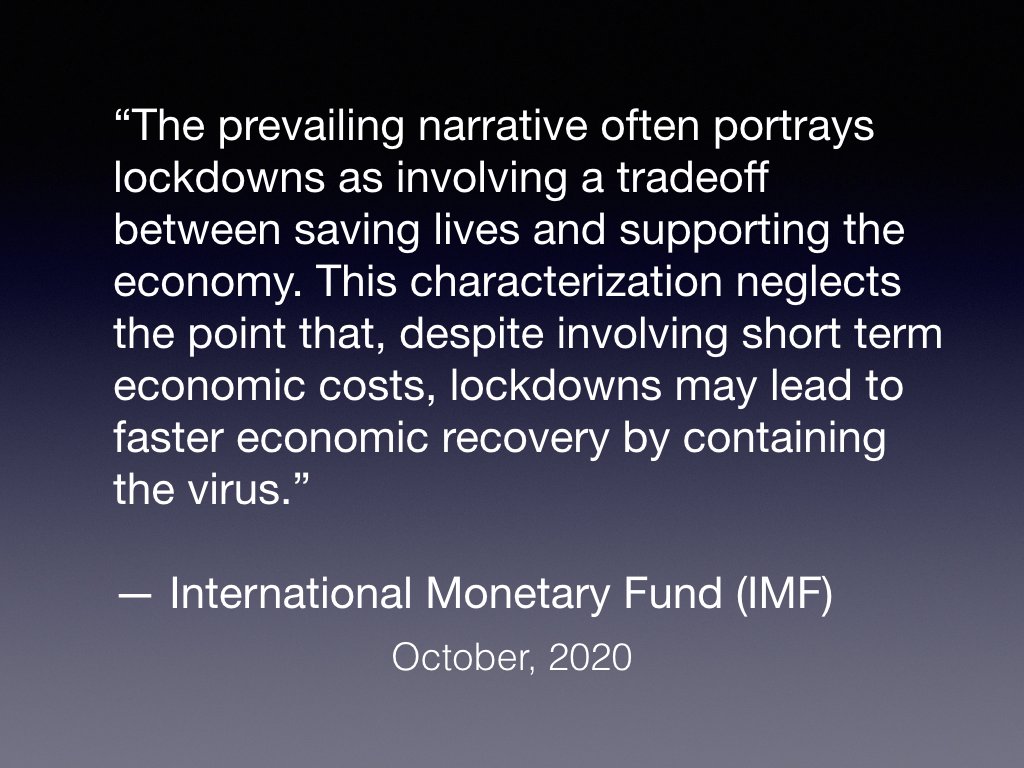

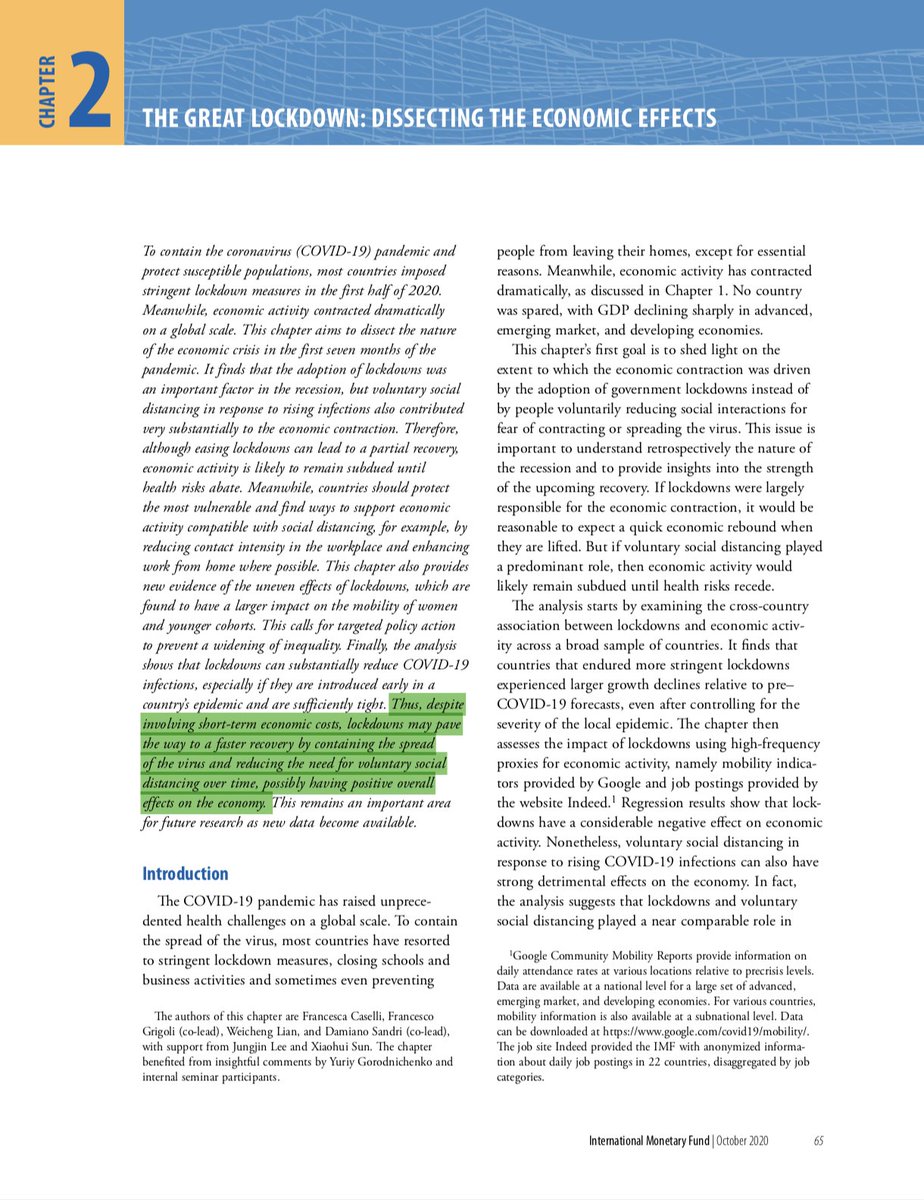

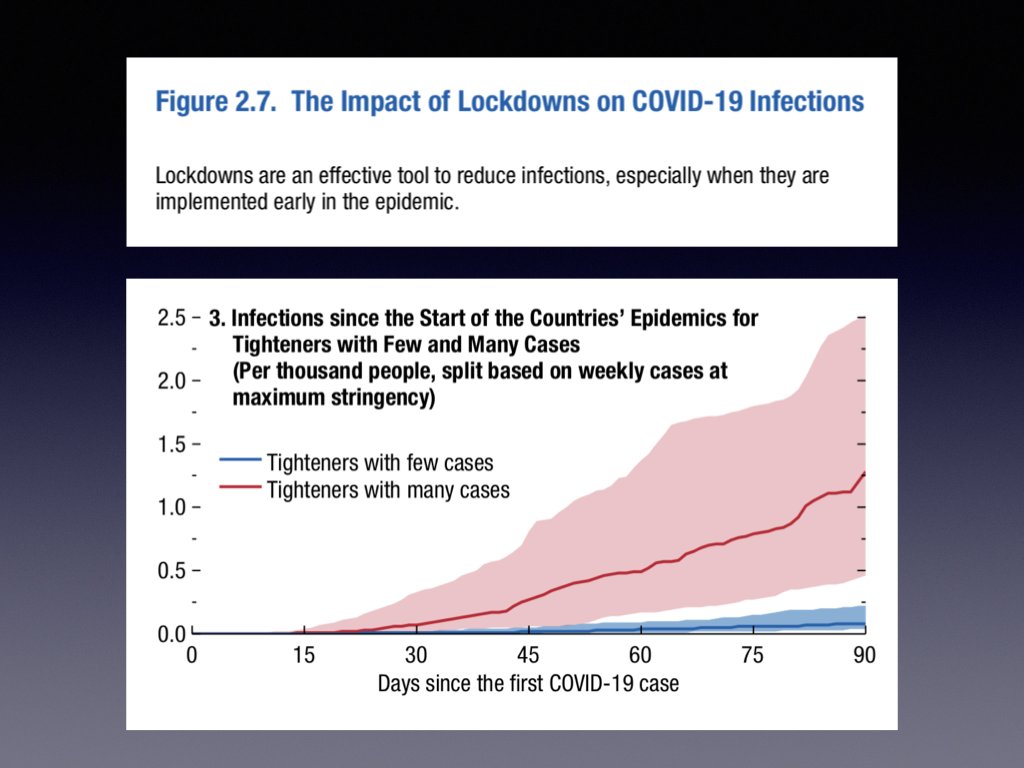

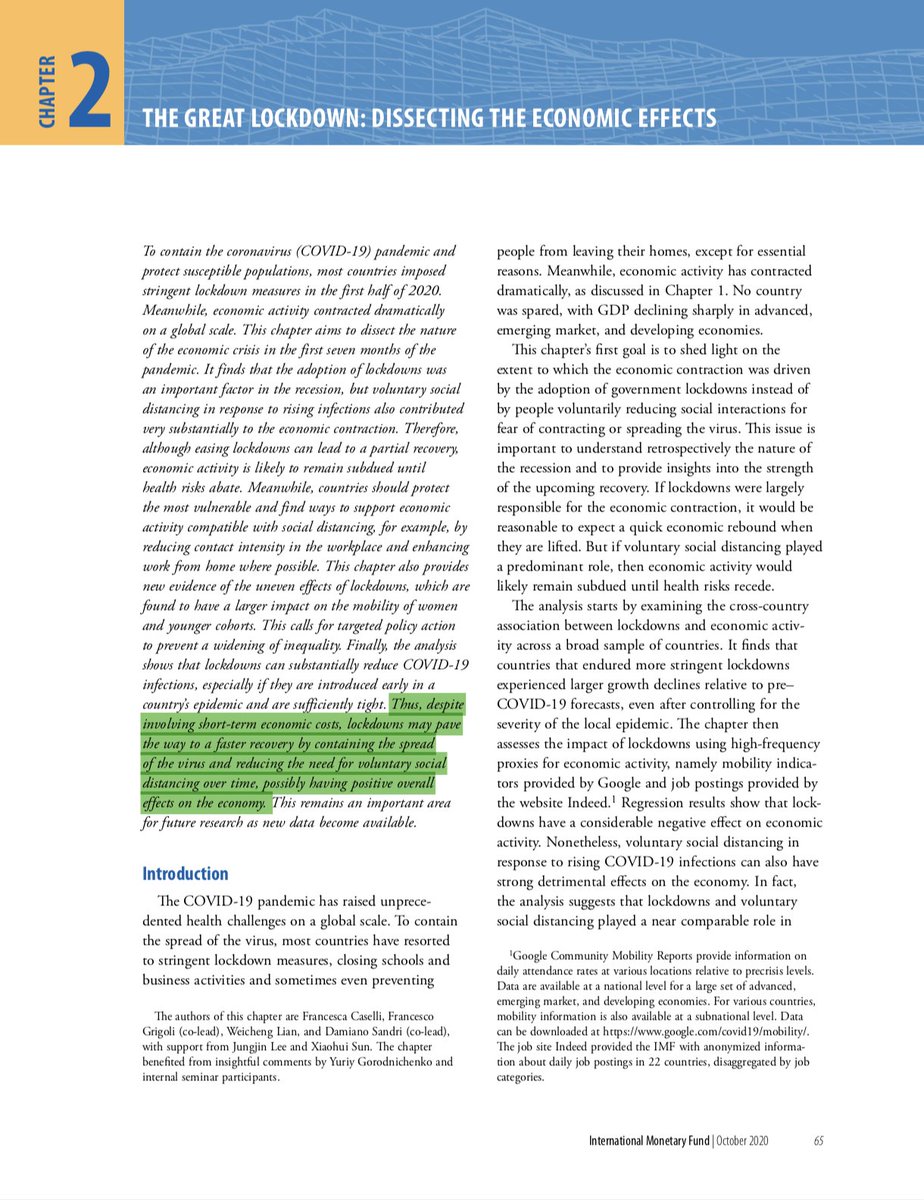

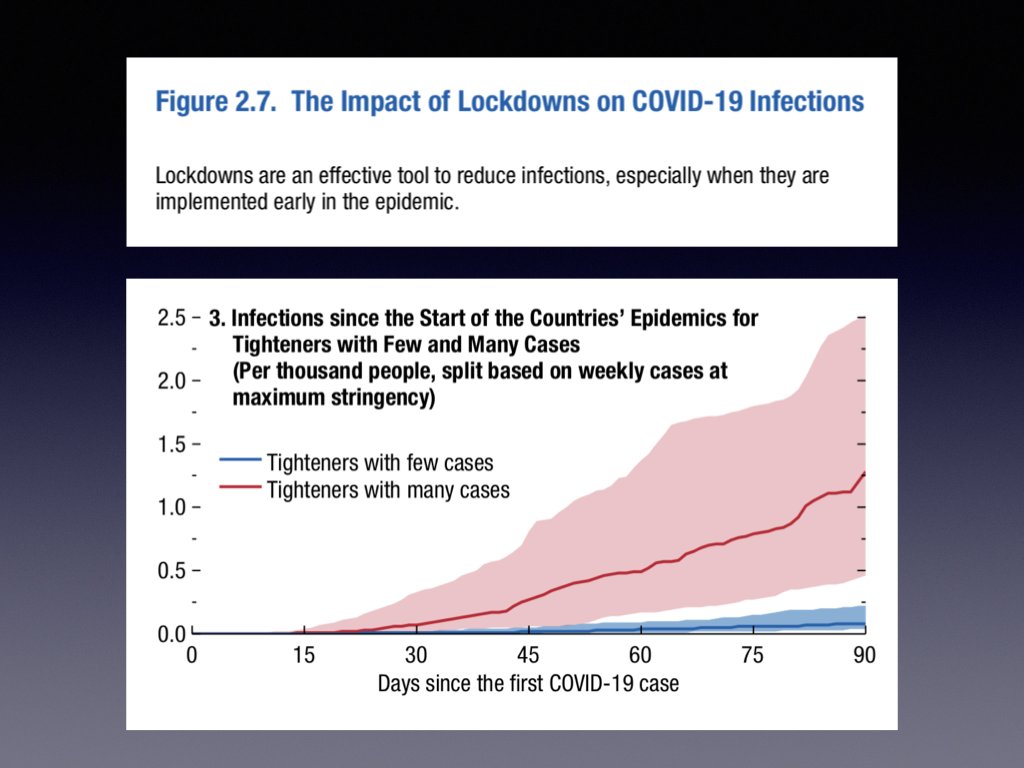

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is analyzing damage due to COVID and projecting further severe consequences if current policies persist. They state “despite involving short term economic costs, lockdowns may lead to faster economic recovery by containing the virus”

1/

Note: This report doesn’t do a dynamic analysis that makes things much clearer, but it does a thoughtful statistical analysis based upon increasingly available data.

https://t.co/5Xmt8y7lCL

A few more quotes:

2/

“The analysis also finds that lockdowns are powerful instruments to reduce infections, especially when they are introduced early in a country’s epidemic and when they are sufficiently stringent.”

3/

“lockdowns become progressively more effective in reducing COVID-19 cases when they become sufficiently stringent. Mild lockdowns appear instead ineffective at curbing infections.”

4/

“The results suggest that to achieve a given reduction in infections, policymakers may want to opt for stringent lockdowns over a shorter period rather than prolonged mild lockdowns...

5/

1/

Note: This report doesn’t do a dynamic analysis that makes things much clearer, but it does a thoughtful statistical analysis based upon increasingly available data.

https://t.co/5Xmt8y7lCL

A few more quotes:

2/

“The analysis also finds that lockdowns are powerful instruments to reduce infections, especially when they are introduced early in a country’s epidemic and when they are sufficiently stringent.”

3/

“lockdowns become progressively more effective in reducing COVID-19 cases when they become sufficiently stringent. Mild lockdowns appear instead ineffective at curbing infections.”

4/

“The results suggest that to achieve a given reduction in infections, policymakers may want to opt for stringent lockdowns over a shorter period rather than prolonged mild lockdowns...

5/

One of the hardest problems post-pandemic will be how to revive so-called "left behind" places.

Post-industrial towns, run-down suburbs, coastal communities - these places were already struggling before the crisis and have fared worst in the last year.

What should we do?

Today, @ukonward sets out the beginning of a plan to repair our social fabric. It follows our extensive research over the last year, expertly chaired by @jamesosh, and funded by @jrf_uk, @Shelter and @peoplesbiz.

https://t.co/d3T5uPwG9N

Before I get into recommendations, some findings from previous Onward research.

In 2018, we found 71% of people believe "community has declined in my lifetime"

In 2019, we found 65% would rather live in “a society that focuses on giving people more security” vs 35% for freedom

This was the basis for our identification of 'Workington Man' as the archetypal swing voter in 2019, and led us to predict (correctly) that large numbers of Red Wall seats could fall. A key driver was a desire for security, belonging and pride in place.

There is also a key regional dimension to this. We also tested people's affinity with the UK's direction of travel, across both cultural and economic dimensions - revealing the extraordinary spread below: London vs. the Rest.

https://t.co/HrorW4xaLp

Post-industrial towns, run-down suburbs, coastal communities - these places were already struggling before the crisis and have fared worst in the last year.

What should we do?

Today, @ukonward sets out the beginning of a plan to repair our social fabric. It follows our extensive research over the last year, expertly chaired by @jamesosh, and funded by @jrf_uk, @Shelter and @peoplesbiz.

https://t.co/d3T5uPwG9N

Before I get into recommendations, some findings from previous Onward research.

In 2018, we found 71% of people believe "community has declined in my lifetime"

In 2019, we found 65% would rather live in “a society that focuses on giving people more security” vs 35% for freedom

This was the basis for our identification of 'Workington Man' as the archetypal swing voter in 2019, and led us to predict (correctly) that large numbers of Red Wall seats could fall. A key driver was a desire for security, belonging and pride in place.

There is also a key regional dimension to this. We also tested people's affinity with the UK's direction of travel, across both cultural and economic dimensions - revealing the extraordinary spread below: London vs. the Rest.

https://t.co/HrorW4xaLp

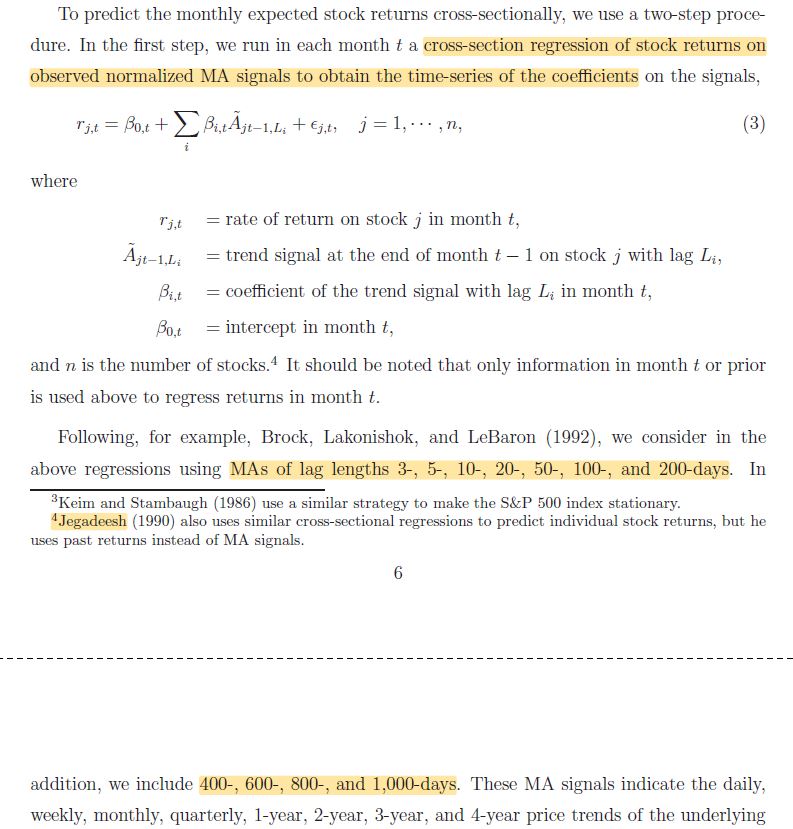

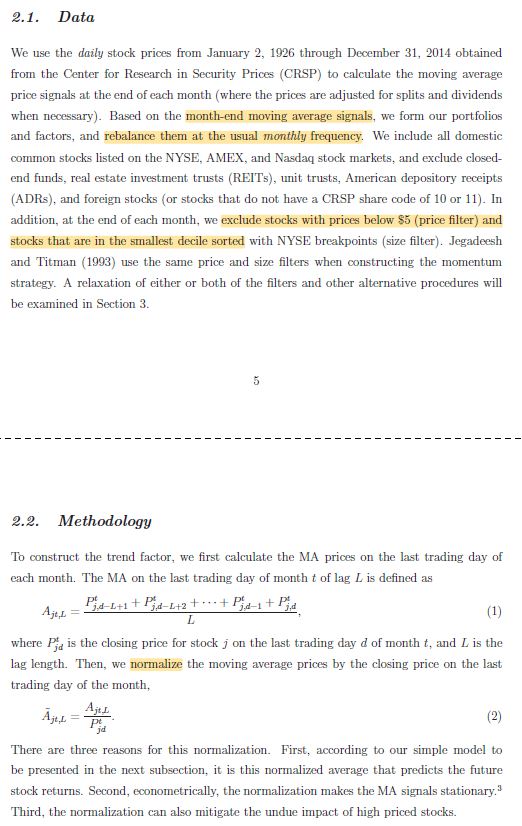

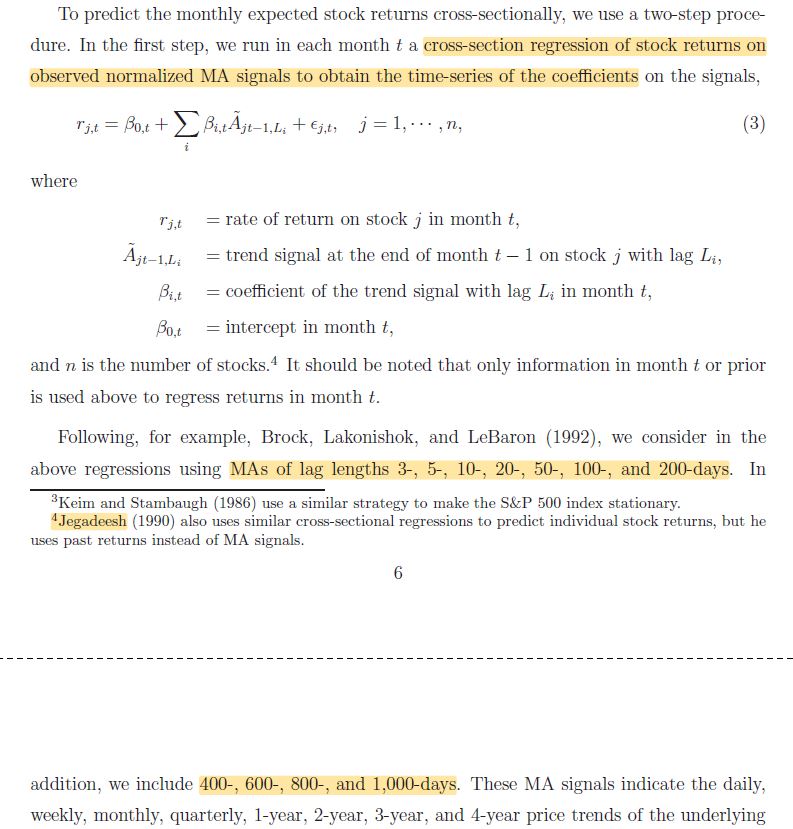

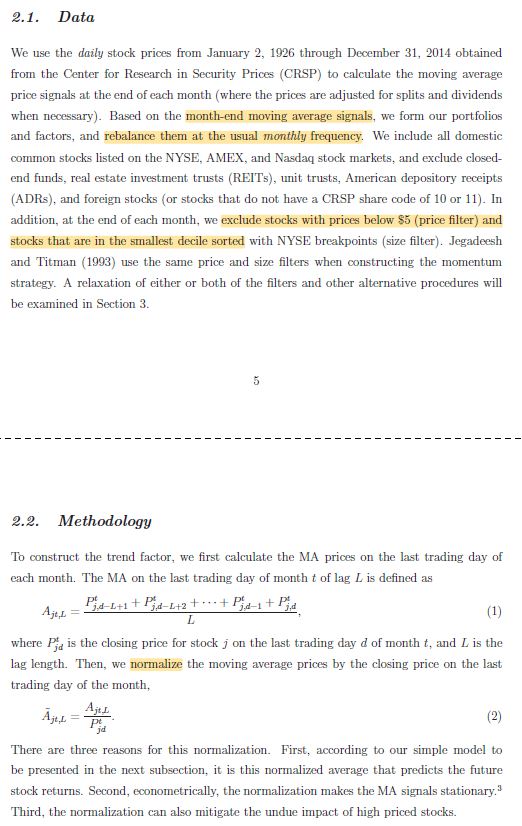

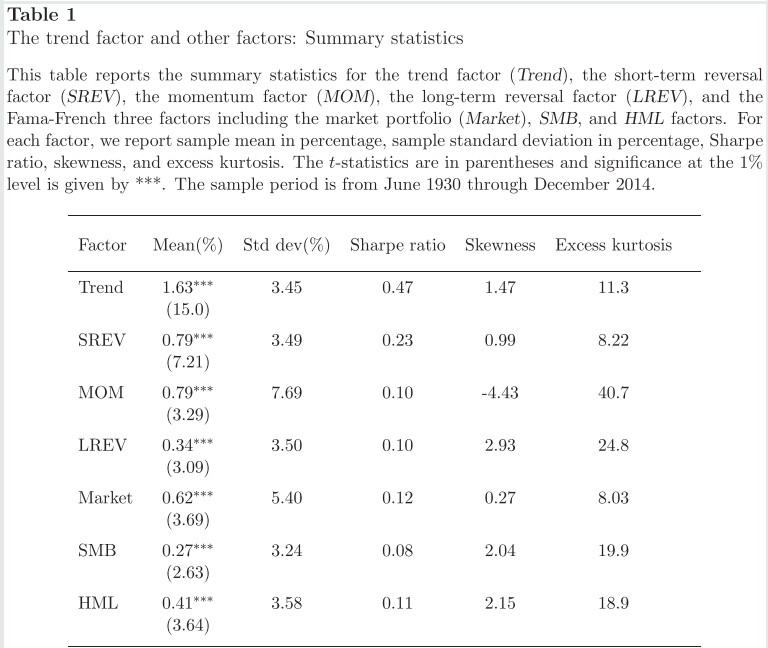

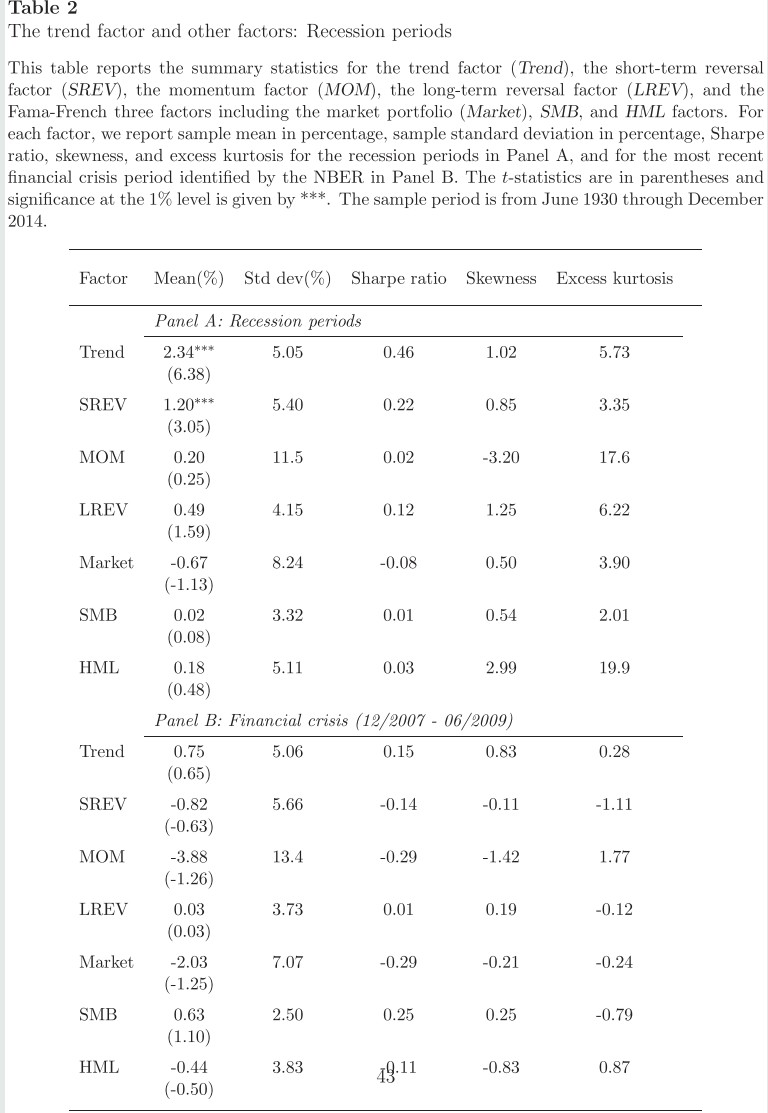

1/ Trend Factor: Any Economic Gains from Using Information over Investment Horizons? (Han, Zhou, Zhu)

"A trend factor using multiple time lengths outperforms ST reversal, momentum, and LT reversal, which are based on the three price trends separately."

https://t.co/udkvsdw2Lz

2/ This resembles combining multiple measures of ST reversal, momentum, and LT reversal (forecasts determined by walking forward rather than using signs from the full sample).

Unlike normal moving average signals, these are *cross-sectional.* More below:

https://t.co/wkIFLg9jtK

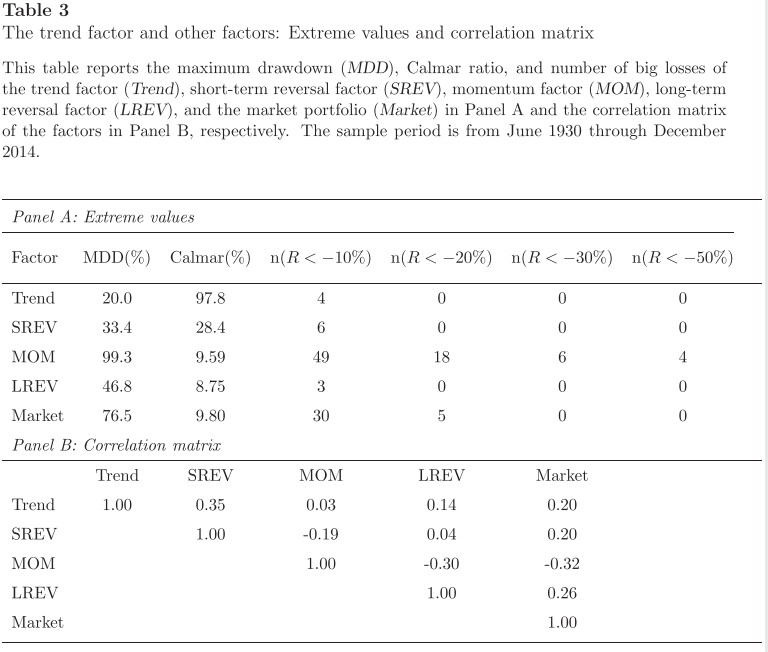

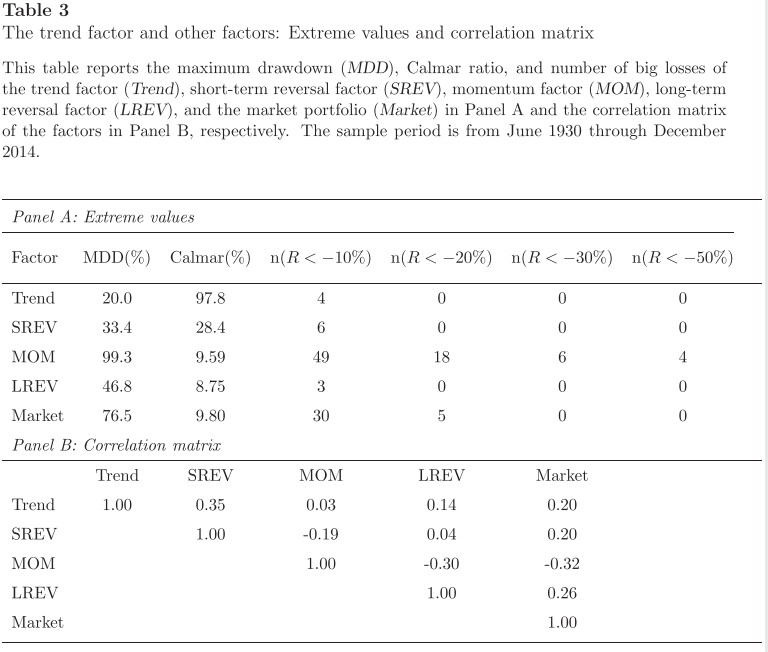

3/ Unsurprisingly, the Trend factor formed by this approach outperforms benchmarks in terms of both Sharpe ratio and tail metrics. It's combining momentum with two factors that are negatively correlated to it AND using multiple specifications.

More here:

https://t.co/x8Tloz3iyL

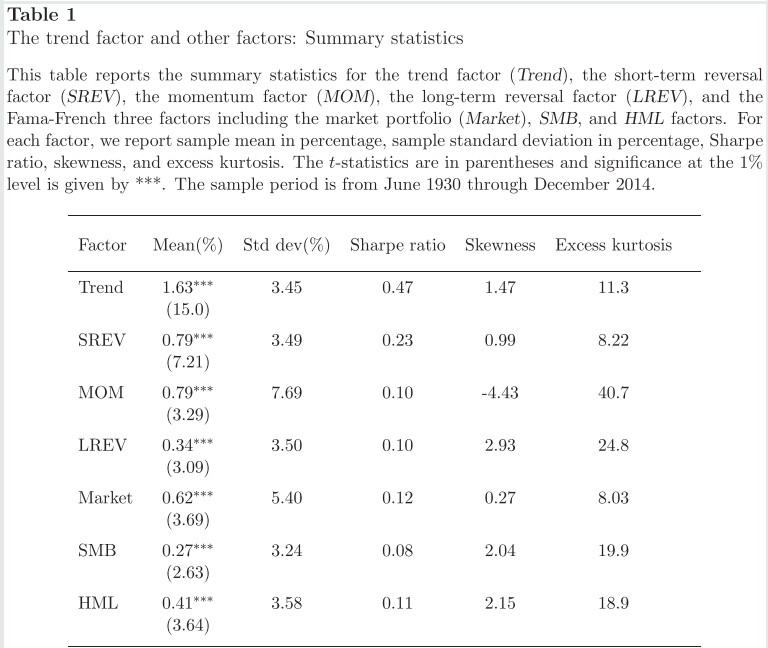

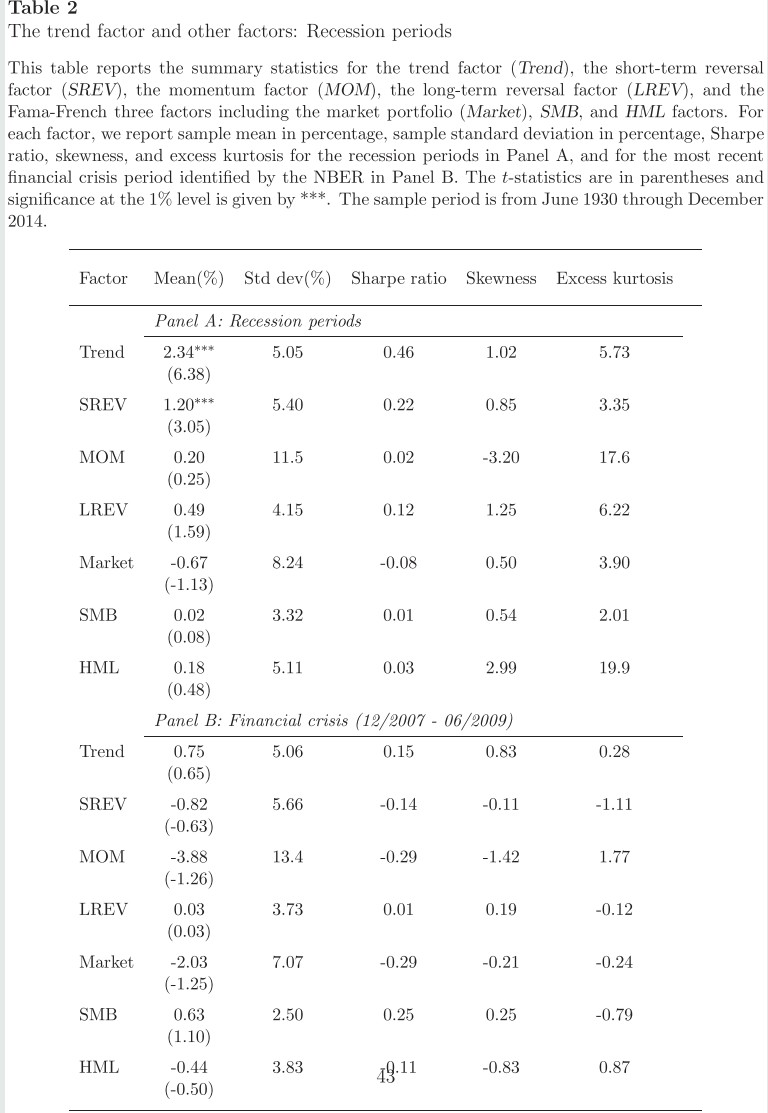

4/ "Average return and volatility of the trend factor are both higher in recession periods. However, the Sharpe ratio is virtually the same.

"Interestingly, all of the factors still have positive average returns.

"Momentum experiences the greatest increase in volatility."

5/ "In terms of maximum drawdown and the Calmar ratio, the trend factor performs the best.

"The trend factor is correlated with the short-term reversal factor (35%), long-term reversal factor (14%), and the market (20%) but is virtually uncorrelated with the momentum factor."

"A trend factor using multiple time lengths outperforms ST reversal, momentum, and LT reversal, which are based on the three price trends separately."

https://t.co/udkvsdw2Lz

2/ This resembles combining multiple measures of ST reversal, momentum, and LT reversal (forecasts determined by walking forward rather than using signs from the full sample).

Unlike normal moving average signals, these are *cross-sectional.* More below:

https://t.co/wkIFLg9jtK

1/ Cross-Sectional and Time-Series Tests of Return Predictability: What Is the Difference? (Goyal, Jegadeesh)

— Darren \U0001f95a (@ReformedTrader) June 18, 2019

"The difference between the performances of TS and CS strategies is largely due to a time-varying net-long investment in risky assets."https://t.co/CSIn3ujN2R pic.twitter.com/XHnVmIart4

3/ Unsurprisingly, the Trend factor formed by this approach outperforms benchmarks in terms of both Sharpe ratio and tail metrics. It's combining momentum with two factors that are negatively correlated to it AND using multiple specifications.

More here:

https://t.co/x8Tloz3iyL

1/ An Executive Summary (in Tweet form) of our new paper

— Adam Butler (@GestaltU) March 27, 2019

Dual Momentum \u2013 A Craftsman\u2019s Perspective

Download here: https://t.co/Y9GlGNohBg

Everything that follows in this thread is based on HYPOTHETICAL AND SIMULATED RESULTS. pic.twitter.com/9m5YJnTdtq

4/ "Average return and volatility of the trend factor are both higher in recession periods. However, the Sharpe ratio is virtually the same.

"Interestingly, all of the factors still have positive average returns.

"Momentum experiences the greatest increase in volatility."

5/ "In terms of maximum drawdown and the Calmar ratio, the trend factor performs the best.

"The trend factor is correlated with the short-term reversal factor (35%), long-term reversal factor (14%), and the market (20%) but is virtually uncorrelated with the momentum factor."

You May Also Like

Trending news of The Rock's daughter Simone Johnson's announcing her new Stage Name is breaking our Versus tool because "Wrestling Name" isn't in our database!

Here's the most useful #Factualist comparison pages #Thread 🧵

What is the difference between “pseudonym” and “stage name?”

Pseudonym means “a fictitious name (more literally, a false name), as those used by writers and movie stars,” while stage name is “the pseudonym of an entertainer.”

https://t.co/hT5XPkTepy #english #wiki #wikidiff

People also found this comparison helpful:

Alias #versus Stage Name: What’s the difference?

Alias means “another name; an assumed name,” while stage name means “the pseudonym of an entertainer.”

https://t.co/Kf7uVKekMd #Etymology #words

Another common #question:

What is the difference between “alias” and “pseudonym?”

As nouns alias means “another name; an assumed name,” while pseudonym means “a fictitious name (more literally, a false name), as those used by writers and movie

Here is a very basic #comparison: "Name versus Stage Name"

As #nouns, the difference is that name means “any nounal word or phrase which indicates a particular person, place, class, or thing,” but stage name means “the pseudonym of an

Here's the most useful #Factualist comparison pages #Thread 🧵

What is the difference between “pseudonym” and “stage name?”

Pseudonym means “a fictitious name (more literally, a false name), as those used by writers and movie stars,” while stage name is “the pseudonym of an entertainer.”

https://t.co/hT5XPkTepy #english #wiki #wikidiff

People also found this comparison helpful:

Alias #versus Stage Name: What’s the difference?

Alias means “another name; an assumed name,” while stage name means “the pseudonym of an entertainer.”

https://t.co/Kf7uVKekMd #Etymology #words

Another common #question:

What is the difference between “alias” and “pseudonym?”

As nouns alias means “another name; an assumed name,” while pseudonym means “a fictitious name (more literally, a false name), as those used by writers and movie

Here is a very basic #comparison: "Name versus Stage Name"

As #nouns, the difference is that name means “any nounal word or phrase which indicates a particular person, place, class, or thing,” but stage name means “the pseudonym of an