Happy Monday! Dominion Voting Systems is suing Rudy Giuliani for $1.3 billion.

As Akiva notes, the legal question is going to boil down to something known as "actual malice."

That's a tricky concept for nonlawyers (and often for lawyers) so an explainer might help.

So Dominion sued Rudy for defamation. How are they ever going to allege actual malice? https://t.co/p8d3flDkGm

— Akiva Cohen (@AkivaMCohen) January 25, 2021

If you want to win a defamation case, you have to prove:

(1) that defendant made a false and defamatory statement about you;

(2) to a third party without privilege;

(3) with the required degree of fault;

(4) causing you to suffer damage.

I've been flipping through defamation cases from the court where this case was filed. I'm finding lots of cases that were dismissed because actual malice wasn't adequately pled. I've not yet found one where a case survived.

OK - just found a case where a defamation claim survived a motion to dismiss in D. DC. Let's take a look at what that required.

And even there, the court called it a "close question."

So I hope you can see why, even though the claims are insane and it's clear that Rudy at least should have known they were false, a lot of lawyers are still skeptical of Dominion's chances.

More from Mike Dunford

Oh myyyyyyyyyy

— Mike Dunford (@questauthority) January 25, 2021

Good morning, followers of frivolous election-related litigation - new filings in Seditionists v 117th Congress et al. (aka in re Gondor)

I've really got to get stuff done, but there's time for a really quick overview.

As far as I can tell from the docket, this is the FOURTH attempt in a week to get a TRO; the question the judge will ask if they ever figure out how to get the judge's attention will be "couldn't you have served by now;" and this whole thing is a

The memorandum in support of this one is 9 pages, and should go pretty quick.

But they still haven't figured out widow/orphan issues.

https://t.co/l7EDatDudy

It appears that the opening of this particular filing is going to proceed on the theme of "we are big mad at @SollenbergerRC" which is totally something relevant when you are asking a District Court to temporarily annihilate the US Government on an ex parte basis.

Also, if they didn't want their case to be known as "in re Gondor" they really shouldn't have gone with the (non-literary) "Gondor has no king" quote.

No, this is not a thing that will change the election. At all.

If this is real - and I do emphasize the if - it is posturing by the elected Republican "leadership" of Texas in an attempt to pander to a base that has degraded from merely deplorable to utterly despicable.

Apparently, it is real. For a given definition of real, anyway. As Steve notes, the Texas Solicitor General - that's the lawyer who is supposed to represent the state in cases like this - has noped out and the AG is counsel of

It looks like we have a new leader in the \u201ccraziest lawsuit filed to purportedly challenge the election\u201d category:

— Steve Vladeck (@steve_vladeck) December 8, 2020

The State of Texas is suing Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin *directly* in #SCOTUS.

(Spoiler alert: The Court is *never* going to hear this one.) pic.twitter.com/2L4GmdCB6I

Although - again - I'm curious as to the source. I'm seeing no press release on the Texas AG's site; I'm wondering if this might not be a document released by whoever the "special counsel" to the AG is - strange situation.

Doesn't matter. The Supreme Court is Supremely Unlikely to take this case - their jurisdiction is exclusive, but it's also discretionary.

Meaning, for nonlawyers:

SCOTUS is the only place where one state can sue another, but SCOTUS can and often does decline to take the case.

OK, so since my attempt to sit back while Akiva does all the work of going through the latest proof that not only the pro se have fools for lawyers has backfired, let's take a stroll through the motion for injunctive relief.

They've also got a brief in support of their injunction motion, but I've got client work that needs doing. Hopefully @questauthority has you covered

— Akiva Cohen (@AkivaMCohen) January 4, 2021

At the start, I'd note that the motion does not appear to be going anywhere fast - despite the request that they made over 80 hours ago to have the motion heard within 48 hours.

The most recent docket entries are all routine start-of-case stuff.

Why isn't it going anywhere quickly? Allow me to direct your attention to something that my learned colleague Mr. Cohen said

Folks, judges DO NOT read complaints or petitions when they are filed, and they DO NOT just up and act on the "requests for relief". If you want something, you need to actually ask the court for it by a motion, not just put it in your "here's what we want if we win" section

— Akiva Cohen (@AkivaMCohen) January 4, 2021

Now I'm not a litigator, but if I had an emergency thing that absolutely had to be heard over a holiday weekend, I'd start by reading the relevant part of the local rules for the specific court in which I am filing my case.

In this case, this bit, in particular, seems relevant:

My next step, if I had any uncertainty at all, would be to find and use the court's after-hours emergency contact info. I might have to work some to find it, but it'll be there. Emergencies happen; there are procedures for them.

And then I'd do exactly what they tell me to do.

More from Politics

You May Also Like

Some random interesting tidbits:

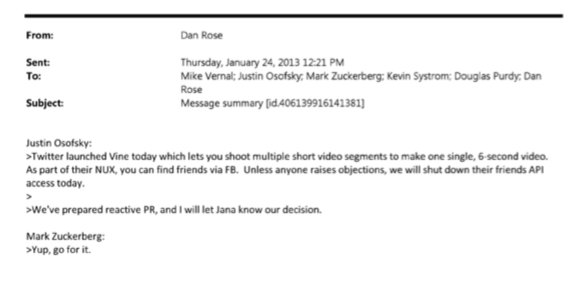

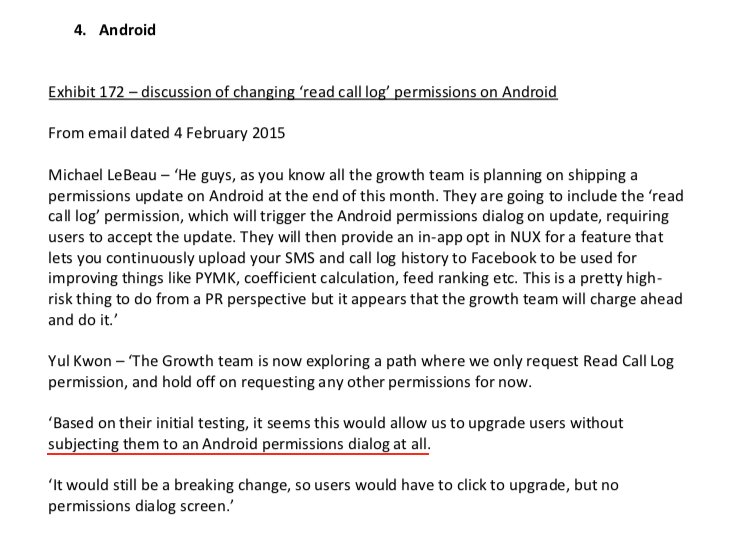

1) Zuck approves shutting down platform API access for Twitter's when Vine is released #competition

2) Facebook engineered ways to access user's call history w/o alerting users:

Team considered access to call history considered 'high PR risk' but 'growth team will charge ahead'. @Facebook created upgrade path to access data w/o subjecting users to Android permissions dialogue.

3) The above also confirms @kashhill and other's suspicion that call history was used to improve PYMK (People You May Know) suggestions and newsfeed rankings.

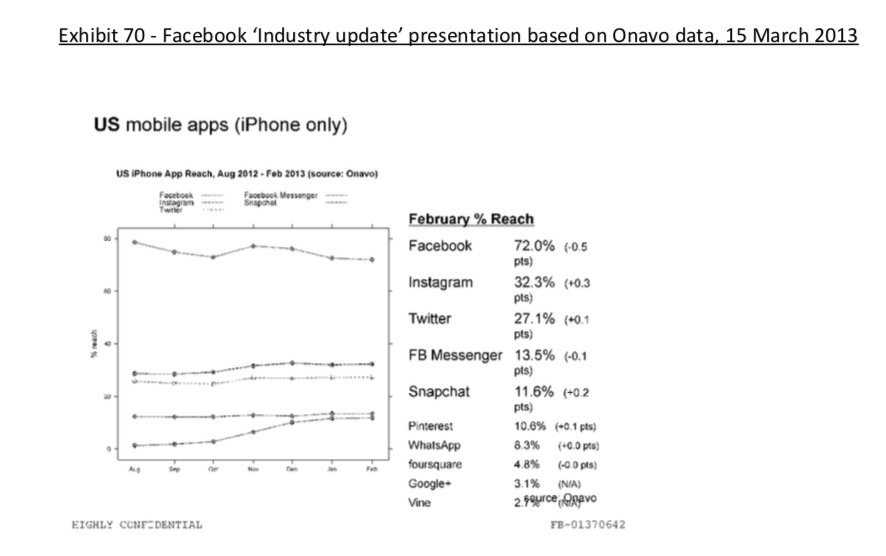

4) Docs also shed more light into @dseetharaman's story on @Facebook monitoring users' @Onavo VPN activity to determine what competitors to mimic or acquire in 2013.

https://t.co/PwiRIL3v9x

For three years I have wanted to write an article on moral panics. I have collected anecdotes and similarities between today\u2019s moral panic and those of the past - particularly the Satanic Panic of the 80s.

— Ashe Schow (@AsheSchow) September 29, 2018

This is my finished product: https://t.co/otcM1uuUDk

The 3 big things that made the 1980's/early 1990's surreal for me.

1) Satanic Panic - satanism in the day cares ahhhh!

2) "Repressed memory" syndrome

3) Facilitated Communication [FC]

All 3 led to massive abuse.

"Therapists" -and I use the term to describe these quacks loosely - would hypnotize people & convince they they were 'reliving' past memories of Mom & Dad killing babies in Satanic rituals in the basement while they were growing up.

Other 'therapists' would badger kids until they invented stories about watching alligators eat babies dropped into a lake from a hot air balloon. Kids would deny anything happened for hours until the therapist 'broke through' and 'found' the 'truth'.

FC was a movement that started with the claim severely handicapped individuals were able to 'type' legible sentences & communicate if a 'helper' guided their hands over a keyboard.