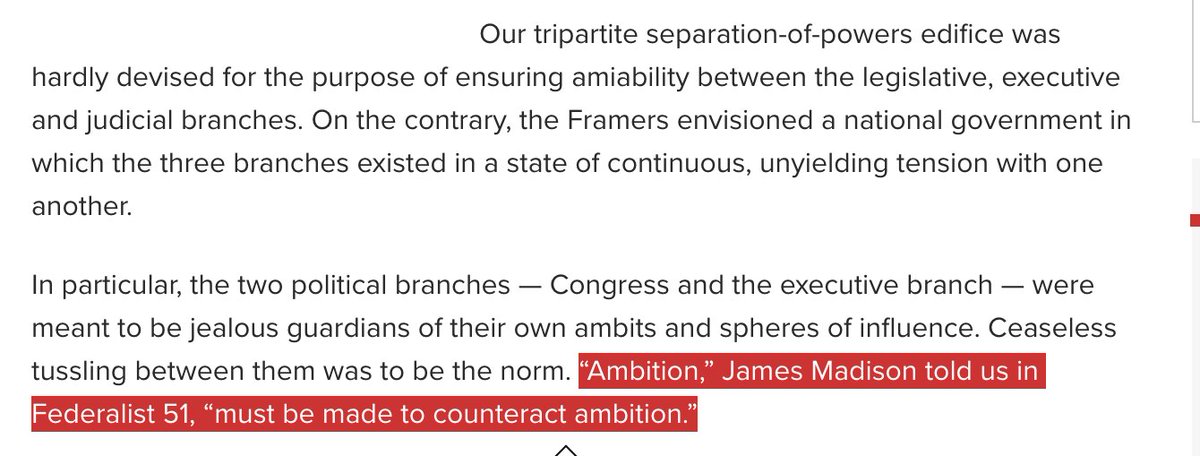

🧵 The conversation surrounding this is confused in ways that really backfire. For example, you often hear that the Founders more or less "wanted gridlock to be the norm," for it to be "hard to get anything done," to guard against radical change.

I cannot explain it, but it seems like the concept of "separation of powers" has become deeply alien and upsetting to most people. *Nothing* can be independent. And so we keep blurring the powers, and it causes systemic dysfunction. There's no long-term view.

— Kerry (@kerry62189) December 24, 2020

More from For later read

And yet authoritarians often broadcast silly, unpersuasive propaganda.

Political scientist Haifeng Huang writes that the purpose of propaganda is not to brainwash people, but to instill fear in them /2

"propaganda is often not used for indoctrination, but rather to signal the government\u2019s strength in being able to afford significant resources and impose on its citizens...not meant to 'brainwash', but rather to forewarn the society about how strong it is" https://t.co/mFAurhEHeO pic.twitter.com/WXKKJaPqWQ

— Rob Henderson (@robkhenderson) June 18, 2020

When people are bombarded with propaganda everywhere they look, they are reminded of the strength of the regime.

The vast amount of resources authoritarians spend to display their message in every corner of the public square is a costly demonstration of their power /3

In fact, the overt silliness of authoritarian propaganda is part of the point. Propaganda is designed to be silly so that people can instantly recognize it when they see it

Authoritarians do not use propaganda for brainwashing, "but to demonstrate their strength in social control...propaganda may need to be dull and unpersuasive, to make sure citizens know it is propaganda when they see it and hence get the implicit message" https://t.co/PqRpxjaIPL pic.twitter.com/1y67d2RCjB

— Rob Henderson (@robkhenderson) June 19, 2020

Propaganda is intended to instill fear in people, not brainwash them.

The message is: You might not believe in pro-regime values or attitudes. But we will make sure you are too frightened to do anything about it.

#Cardano “Understanding Kamali”

#Cardano will be the underpinning of the emergence of Africa.

To grasp the full weight of the SOLUTIONS #Cardano can provide it is pertinent to read “Understanding Africa” as I will draw directly from the PROBLEMS laid out.

(2/50)

Here is a link if you have not already read

(1/38) #Cardano \u201cUnderstanding Africa\u201d (Part 1 of 2)

— FatCat (@fatcatofcrypto) February 10, 2021

This thread will be split into two parts with the 2nd coming out on Sunday.

Part 1 will layout the pervasive PROBLEMS Africa faces whereas Part 2 will apply direct technologies @InputOutputHK can implement as SOLUTIONS. pic.twitter.com/n3I91bnddq

(3/50)

What I will attempt to do here, is to create an immersive world for you to be placed in to grasp the weight and size of problems from the ground level and then take a grass-roots approach at solving them using #Cardano and its technology.

(4/50)

As an investor and community member of #Cardano, this should be extremely important to you as you have a stake (pun intended) in this.

“You are paid in direct proportion to the difficulty of the problems you solve” - @elonmusk

(5/50)

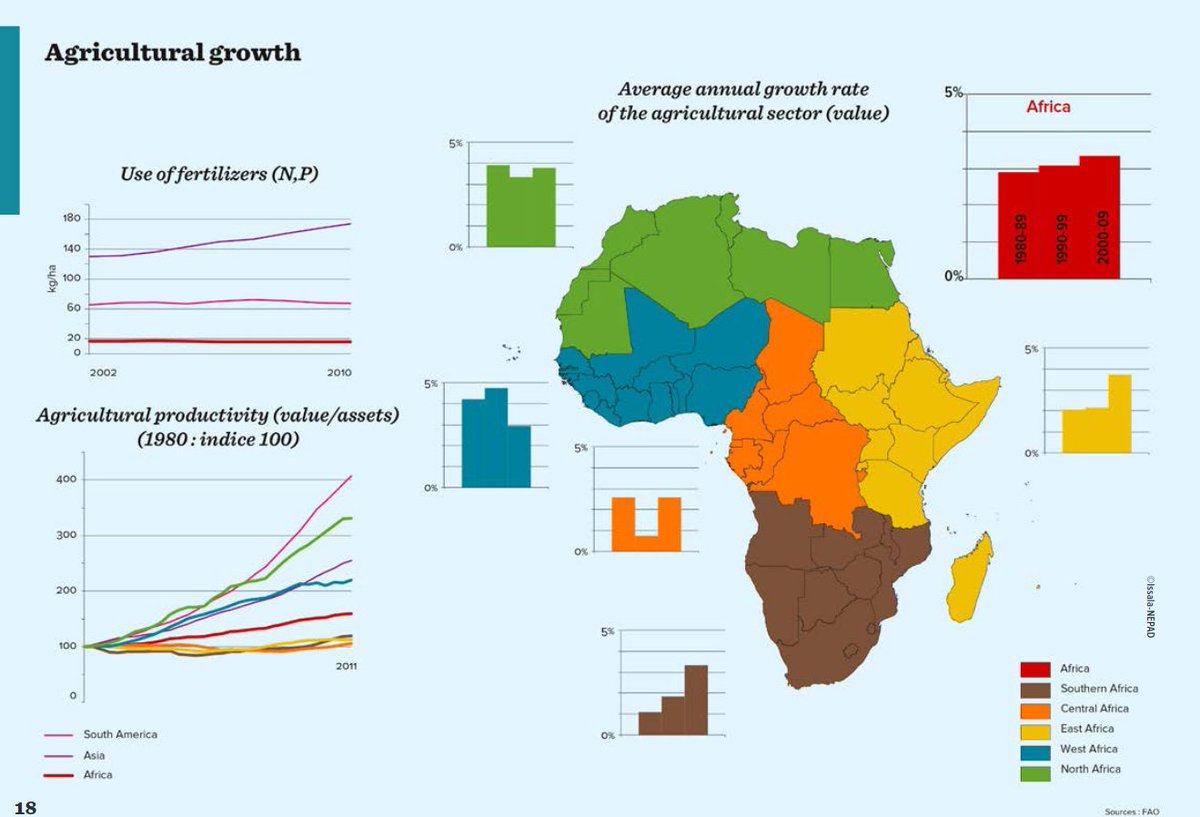

In Africa, agribusiness, more than any other sector, has the potential to reduce poverty and drive economic growth. Agriculture accounts for nearly half of the continent’s gross domestic product and employs 60 percent of the labor force.

Raise your hand if you\u2019ve lost a case despite having the law, facts, quality lawyering, and justice on your side.

— Jon Feinberg (@JonFeinberg) February 13, 2021

Bail arguments, motions, oral arguments, hearings. Judges don’t know, follow, or care about the law. Prosecutors are willing to take advantage of it. And mandatory minimums, withheld evidence, & pretrial detention coerces people to plead before trial. When theres a jury. A shot.

But defenders still fight. And still win. Most times wins aren’t “Justice.” It’s power of repetition of argument in front of same judges. Introducing those in power to the people they oppress. Not just a RAP sheet or words on a page. Defenders make it harder to be brutal & cruel.

I worked as a public defender at an office as well resourced as any in the country. Social workers, team of investigators, a reentry team, support staff, specialist attorneys in immigration, housing, education, family. Relatively low caseloads (80-100). And yet still injustice.

Most think that balancing the scales of justice means more funding for defenders. Thats part of it. Enough a attorneys to actually be at bail hearings. Wrap around services to be able to help people trapped in the system end up better off in their communities. Lower caseloads.

You May Also Like

Unfortunately the "This work includes the identification of viral sequences in bat samples, and has resulted in the isolation of three bat SARS-related coronaviruses that are now used as reagents to test therapeutics and vaccines." were BEFORE the

chimeric infectious clone grants were there.https://t.co/DAArwFkz6v is in 2017, Rs4231.

https://t.co/UgXygDjYbW is in 2016, RsSHC014 and RsWIV16.

https://t.co/krO69CsJ94 is in 2013, RsWIV1. notice that this is before the beginning of the project

starting in 2016. Also remember that they told about only 3 isolates/live viruses. RsSHC014 is a live infectious clone that is just as alive as those other "Isolates".

P.D. somehow is able to use funds that he have yet recieved yet, and send results and sequences from late 2019 back in time into 2015,2013 and 2016!

https://t.co/4wC7k1Lh54 Ref 3: Why ALL your pangolin samples were PCR negative? to avoid deep sequencing and accidentally reveal Paguma Larvata and Oryctolagus Cuniculus?

Do Share the above tweet 👆

These are going to be very simple yet effective pure price action based scanners, no fancy indicators nothing - hope you liked it.

https://t.co/JU0MJIbpRV

52 Week High

One of the classic scanners very you will get strong stocks to Bet on.

https://t.co/V69th0jwBr

Hourly Breakout

This scanner will give you short term bet breakouts like hourly or 2Hr breakout

Volume shocker

Volume spurt in a stock with massive X times