Around 2012, while on summer break from what I felt was a lackluster school year, I was kind of at a breaking point. A prominent designer was peddling this self-help program, a $6000 weeklong workshop that centered around dinner with him and his influential friends.

His response to a fan who was deeply inspired by him and wanted to be a better designer, who asked "what if I can't afford the $6000?" was "You simply don't *want* to afford it." It's not a priority for you. I remember seeing it on Facebook and getting up from my chair.

It was gross, and it felt like the latest incident in what seemed like a long generational road of manipulating impressionable young people into thinking that the only thing stopping them from having the lives of these visible figures was passion

It felt wrong. Absolutely wrong. I thought about my best friend from high school. Someone just as—if not more—talented than me in art. Both of us dreamed of going to the same art school. Only one of us did. His familial socioeconomics as his undocumented status made it impossible

Thankfully, within a year, the conversation shifted. I think many people felt what I felt. A lot of people including myself started speaking out not just about more systemic issues within the design industry but about how "do what you love" was in many ways, a scam

Slate published this in 2014, and it felt like truth was being told that "Do what you love" is a privilege afforded to a select few. It didn't take long before it became "unpaid internships are for rich kids and most cool designers come from wealth"

https://t.co/t45QAkAC1R

And while there's obviously some truth to that, I think in the six years since, this message has continued to mutate and during that time, I think we have started to over-index on this POV to a whole new generation of students.

The last class I taught was in 2016, and even then I could feel something was different. There was a pervading hopelessness that wasn't there when I was in school.

And from what I'm observing at a distance, it seems like it's on steroids now. A whole generation of students told that if they don't come from money, they probably won't get to go through the process of being independent and working on projects they genuinely enjoy.

It was meant to be a response to an overly-pervasive culture of over-indexing on passion. It was meant to be an encouraging note to students who were being gaslit by everything around them that suggested that racism, sexism, classism didn't factor into the opportunities they had

But now it became the main message—and I'm not sure it's actually helped and I fear it's actually been destructive. It's made a lot of people "feel better" but I don't know if it actually was better. In the end, the least empowered were made to feel even more disempowered

Somewhere along the line "Don't pretend the storm isn't coming" translated into "Spend all your energy cursing the clouds" and not "Spend time on re-enforcing your home"

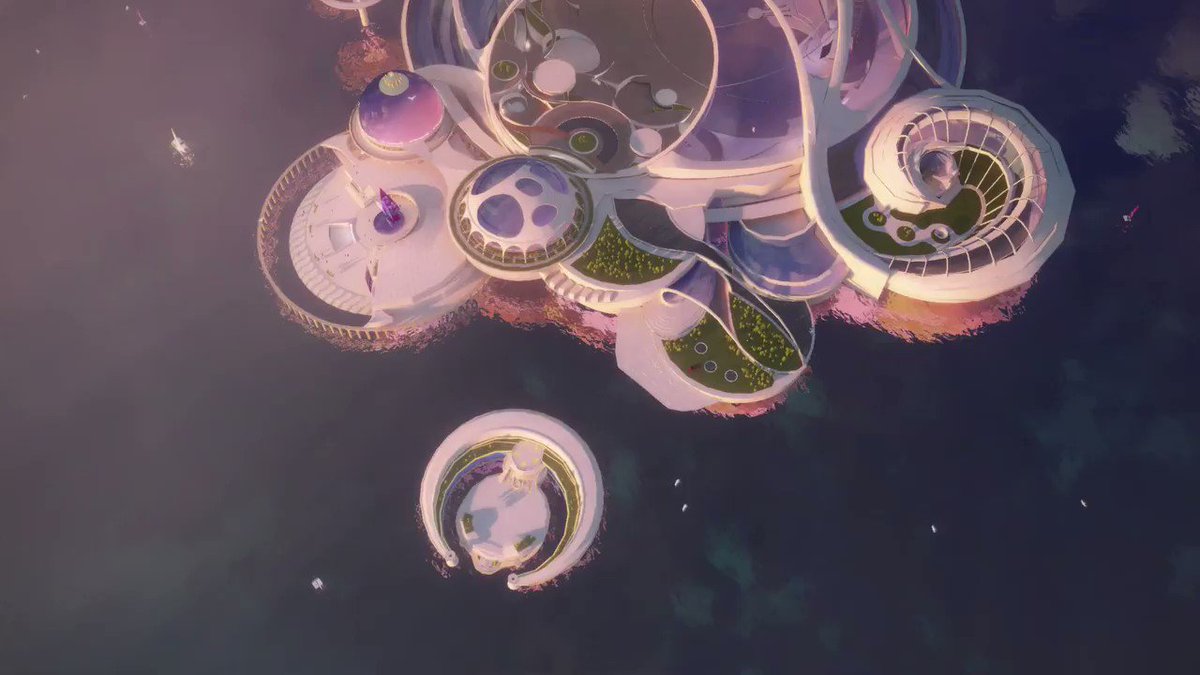

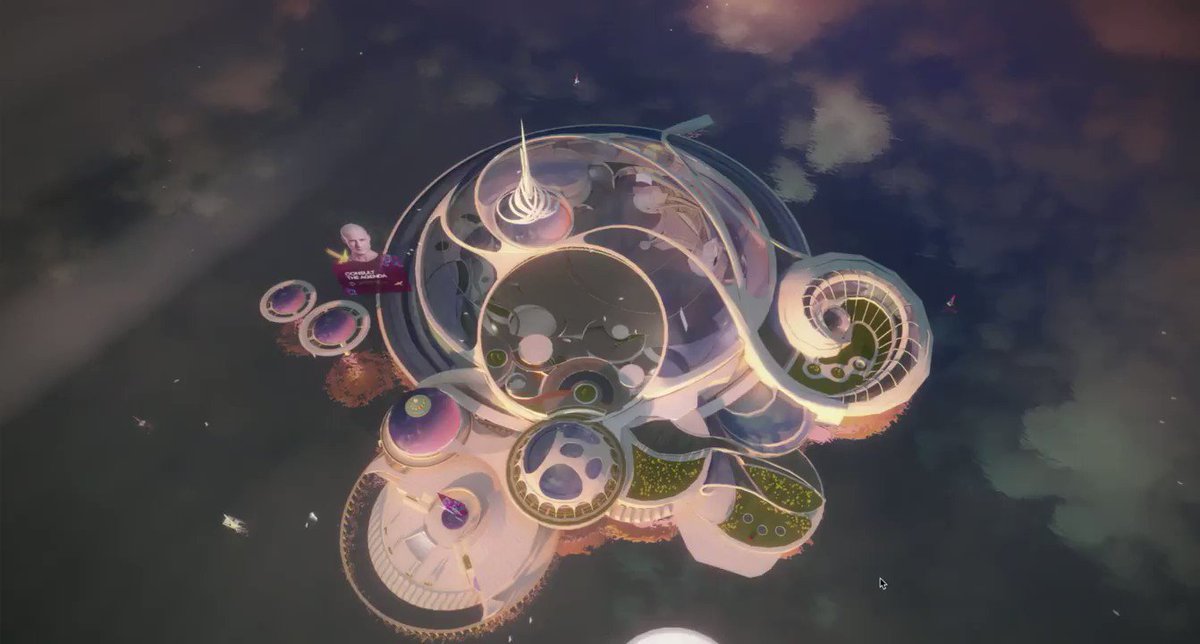

Somewhere along the line, "These institutions of education and industries were designed to enable a few select people" translated into "Don't even think about going near this" and not "Support yourself and your friends and build new things and rely less on the old stuff"

Somewhere along the line, "Working for a small boutique agency or art institution is in many ways just as exploitative and unfulfilling as working for a big corp" translated into "Working at Facebook is morally superior to working for OK-RM because privilege"

Who *really* benefits from this in the end? And what should we say instead? How do we not ignore and show compassion towards the lived experiences and realities of others while emphasizing that ultimately we are the strongest advocates for ourselves?

How do affirm the struggles that people face without ignoring the uncomfortable reality that sometimes pretending they're not there *is* actually helpful?

I went through the latter half of the decade carrying parts of me that felt fraudulent and contradictory—unpacking how I attracted an audience from talking about privilege despite having benefitted from many of the systems of which I spoke

while also letting my fixation on what remaining privileges I did not have access to poison me so many parts of me for nearly all of my 20's

I'm going to stop myself before this becomes too inward-looking, but ultimately—and this will sound clumsy as hell— it seems unhealthy to listen too much to people who tell you that you can't do something even if they claim that it's coming from a woke place.

And while barriers of all shapes and sizes are very much real, there's no situation where advocating for yourself, supporting your friends, constantly learning new things, and not waiting for permission to do something won't get you further than you thought possible.