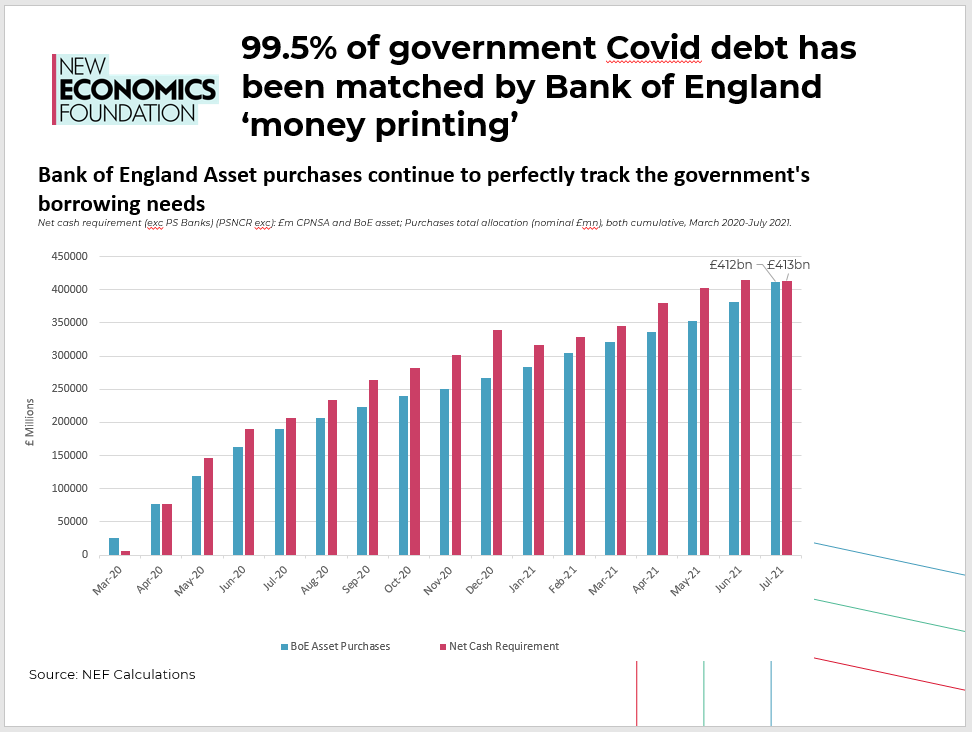

Not too long ago, the state of public finances was thought to be giving chancellor

@RishiSunak “sleepless nights”. But then it became clear that the

@BankofEngland was helping bankroll the Coronavirus bill.

@spencershapland @KateAndrs 2/

In almost a blink of an eye, it was as if the last ten years of devastating public spending cuts may have been for naught, some suggested the 'fig leaf'🍃 had been removed:

3/

https://t.co/2kLj7YikDz

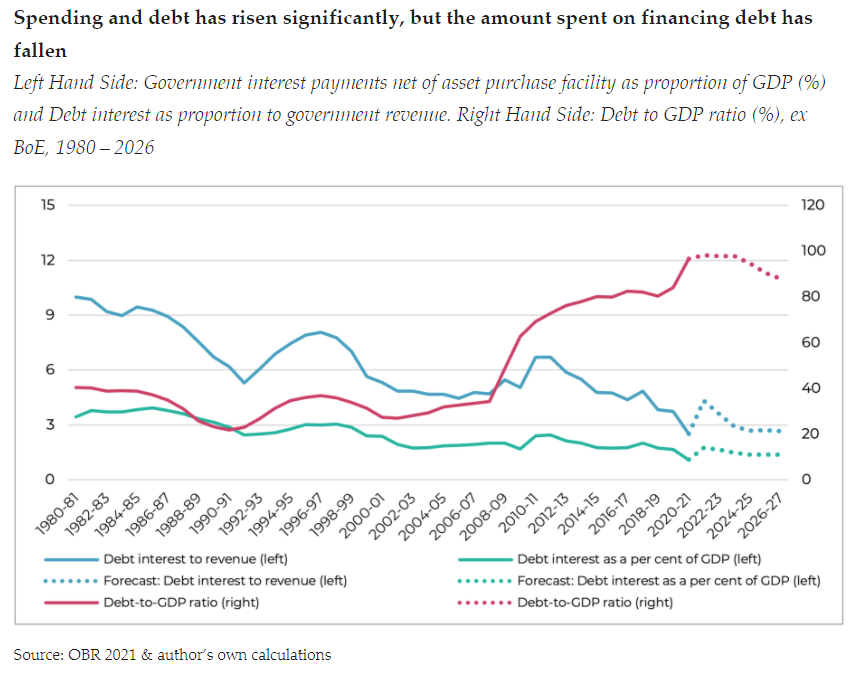

As the penny dropped, the majority of public commentary began to show a greater appreciation for the fact that debt and deficit levels are less important than the actual cost of servicing debt.

4/

See here for explainer👇👇👇:

https://t.co/hMl4WyAdDr

But just as it seemed the penny was beginning to drop, new excuses for low/borrowing investment were being conjured. Despite borrowing costs having reached historical lows, "deficit fetishism" turned into "inflation and interest rates" fetishism 😱😱😱...

5/

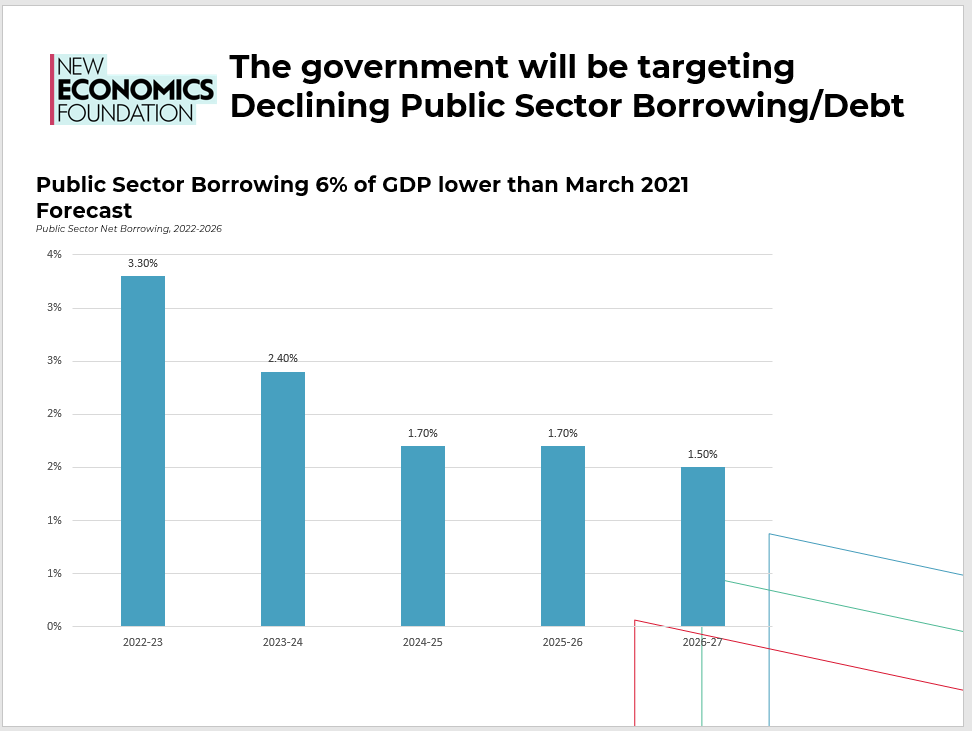

The new fetish means borrowing over the next 5 years is forecast to be 6% lower than in March 2021. As a result,

@hmtreasury will only be deploying £25.5bn of 🌍net zero🌍 spending between 2021 – 2025, when it should be at least £30bn a year.

6/

https://t.co/8grpUXQzzb

A 1% increase in inflation and interest rates would increase the cost of servicing debt by £23bn. Factoring in higher projected future inflation and interest rates, the

@OBR_UK forecast that debt servicing costs will rise to a total of £40 billion in 2022 and 2023.

7/

While these figures should not be taken lightly, and the rising costs of living is serious, there are a number of reasons why we should not rush to the panic button.

8/

As a proportion of the economy, debt servicing costs in 2022 and 2023 will still only be 1.6 and 1.7% of GDP and a percentage of the tax take 4.3% and 3.6% — similar levels as 2018 – 2019 and still lower than at any time in the preceding three centuries. h/t

@JoMicheII 9/

This suggests there is significantly more headroom for borrowing to bring the economy to full output capacity by supporting the low-carbon transition and well-paid green jobs.

10/

See

@NEF: CALLING TIME: Replacing the fiscal rules with fiscal referees

https://t.co/lKMudLOYn6

There is a separate question around whether interest rates may have to rise because of a sudden loss of investor confidence. Unlikely! In its recent £6 billion sale of green gilts, the UK Debt Management Office (DMO) received £74 billion in subscriptions h/t

@billy_blog 11/

What if the BoE decides to raise rates? The first answer is that the Bank shouldn’t raise rates, especially not past that forecasted by the OBR – in response to a largely externally conditioned supply-side crisis and given the frail state of the UK’s economic recovery.

12/

Inflation not being driven by domestic pressures – like an increase in wages and is likely to be transitory. An increase in the Bank’s interest rates will not help solve global supply chain issues, or reduce any of the pain caused by labour shortages associated with Brexit.

13/

Instead it will translate into higher costs for families, raise costs for businesses, weaken the economic recovery. The Eurozone learned a harsh lesson by raising interest rates too soon after the 2008 global financial crisis. See

@AntonioFatas 14/

https://t.co/pi9tglEmbd

The scenario where base rates go up beyond

@OBR_UK forecast, is one where the economy is recovering, jobs and household incomes are up, and overall demand is boosted. Meaning tax receipts are going up + unemployment (other income) transfers to the private sector are falling.

15/

If necessary, the BoE could deploy other credit guidance tools to curb aggregate demand, or the Treasury could raise additional taxes if needed.

16/

See our

@jryancollins recently academic published paper (not paywalled)💪💪💪

https://t.co/V1NlgBwW8F

Finally, as a forthcoming NEF

@DominicCaddick working paper will illustrate, the

@bankofengland could move towards a tiered reserve system, substantially reducing the government’s debt servicing cost all together.

17/

See

@WhelanKarl: https://t.co/1lMcdrWBOC

Inflation and its implication for debt servicing costs shouldn’t be taken lightly. But for now, these issues are manageable, if not solvable. With an environmental emergency on our hands – there are other more pressing issues to keep us up at night.

18/

https://t.co/PU9vseeYf7