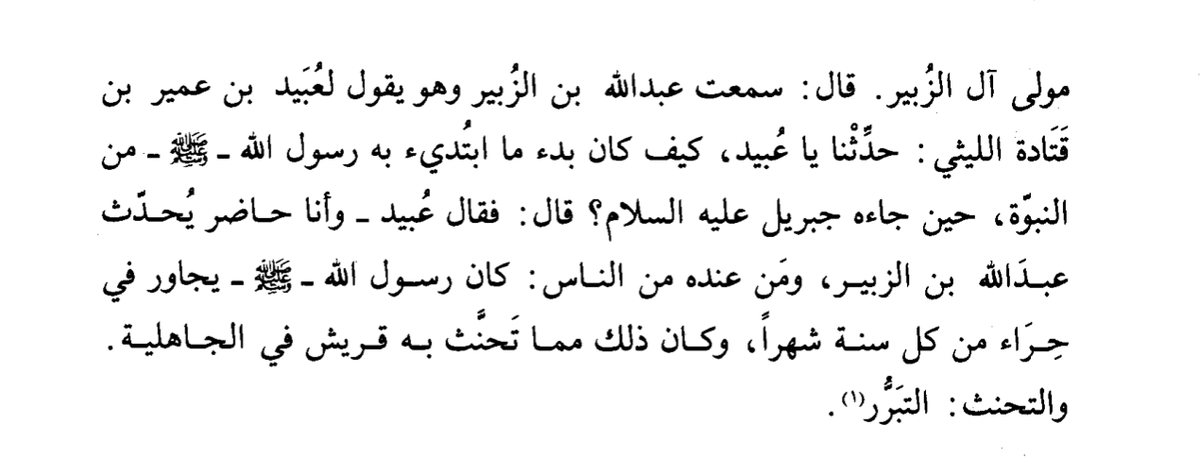

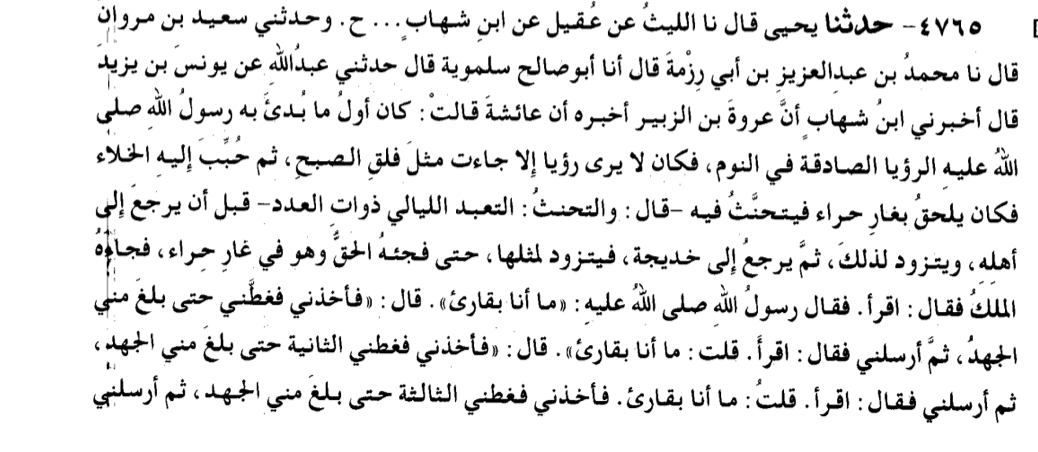

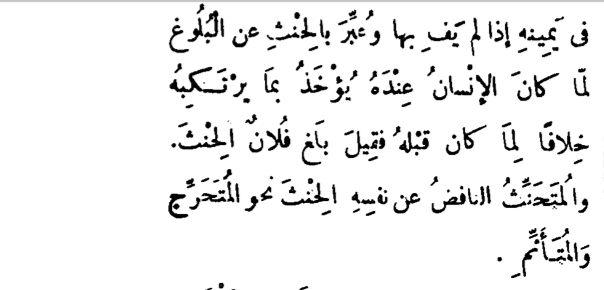

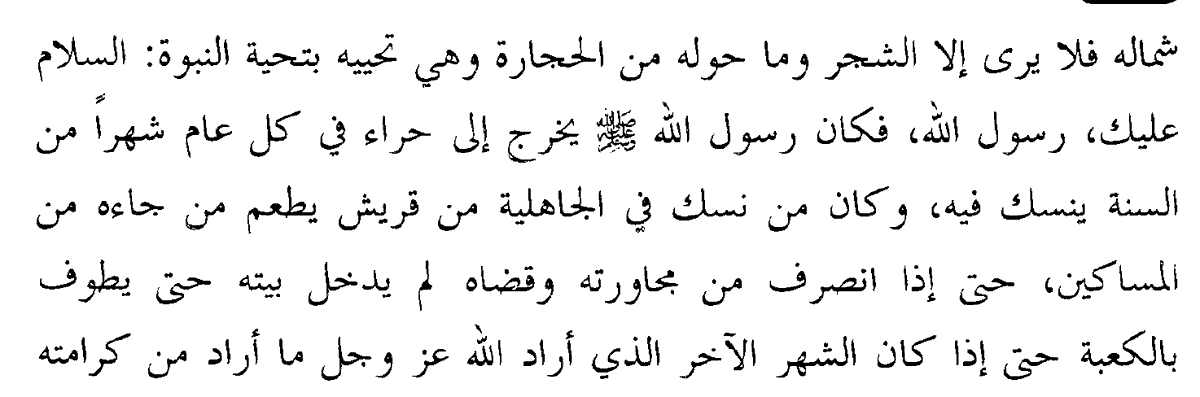

Did the Prophet Muḥammad follow an Arabian religion or religiosity before Islam, that is, before what Muslim accounts label the "Call to Prophecy"? A short thread based on notes for an article preparation 1/

More from World

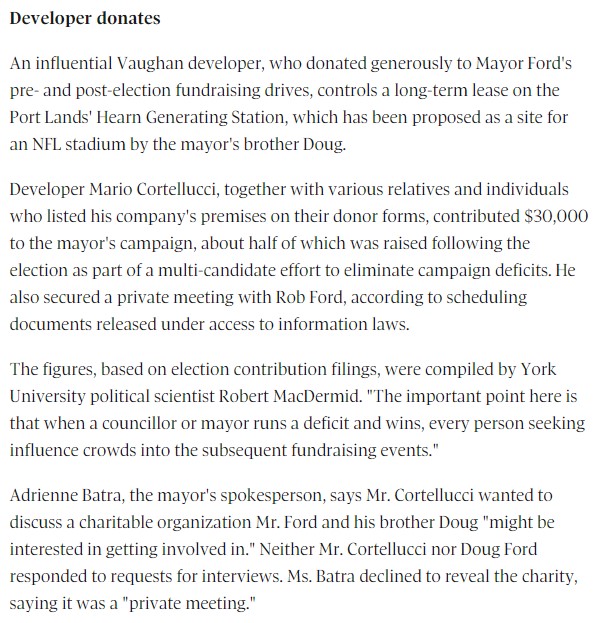

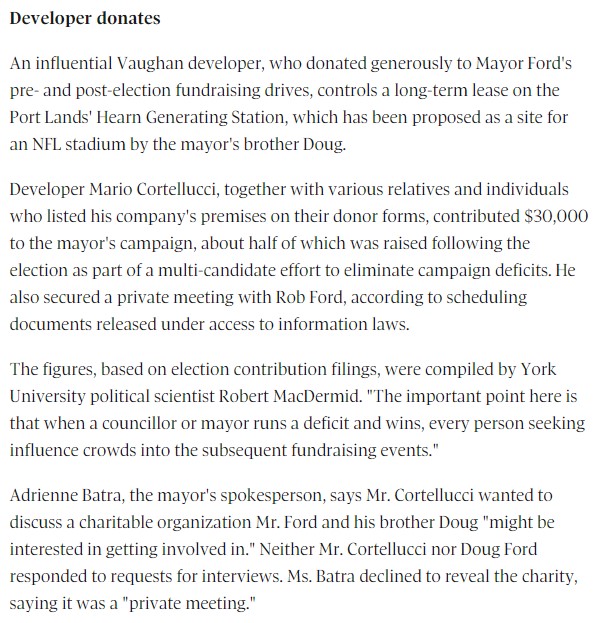

fascinated by this man, mario cortellucci, and his outsized influence on ontario and GTA politics. cortellucci, who lives in vaughan and ran as a far-right candidate for the italian senate back in 2018 - is a major ford donor...

his name might sound familiar because the new cortellucci vaughan hospital at mackenzie health, the one doug ford has been touting lately as a covid-centric facility, is named after him and his family

but his name also pops up in a LOT of other ford projects. for instance - he controls the long term lease on big parts of toronto's portlands... where doug ford once proposed building an nfl stadium and monorail... https://t.co/weOMJ51bVF

cortellucci, who is a developer, also owns a large chunk of the greenbelt. doug ford's desire to develop the greenbelt has been

and late last year he rolled back the mandate of conservation authorities there, prompting the resignations of several members of the greenbelt advisory

his name might sound familiar because the new cortellucci vaughan hospital at mackenzie health, the one doug ford has been touting lately as a covid-centric facility, is named after him and his family

but his name also pops up in a LOT of other ford projects. for instance - he controls the long term lease on big parts of toronto's portlands... where doug ford once proposed building an nfl stadium and monorail... https://t.co/weOMJ51bVF

cortellucci, who is a developer, also owns a large chunk of the greenbelt. doug ford's desire to develop the greenbelt has been

and late last year he rolled back the mandate of conservation authorities there, prompting the resignations of several members of the greenbelt advisory

No surprise that the Russian influence campaign is similar in Australia & the U. S. It's worth watching "Putin’s Patriots: Russian money and influence in Australia" by the ABC

Mitch McConnell's buddy, Oleg Deripaska, is

Let's not forget that McConnell enabled sanctions to be lifted from Deripaska's companies, EN+, Rusal, and EuroSibEnergo, even though a bipartisan group of Senators were against

https://t.co/RlIDzdUOD3

Deripaska's Rusal then invested $200M in a proposed KY aluminum mill. McConnell's statement that this had nothing to do with blocking the vote against allowing the Treasury Dept. to lift sanctions is

Article that ABC published covering the same information that is in the above linked broadcast on

Mitch McConnell's buddy, Oleg Deripaska, is

Let's not forget that McConnell enabled sanctions to be lifted from Deripaska's companies, EN+, Rusal, and EuroSibEnergo, even though a bipartisan group of Senators were against

https://t.co/RlIDzdUOD3

Deripaska's Rusal then invested $200M in a proposed KY aluminum mill. McConnell's statement that this had nothing to do with blocking the vote against allowing the Treasury Dept. to lift sanctions is

Article that ABC published covering the same information that is in the above linked broadcast on

You May Also Like

BREAKING: @CommonsCMS @DamianCollins just released previously sealed #Six4Three @Facebook documents:

Some random interesting tidbits:

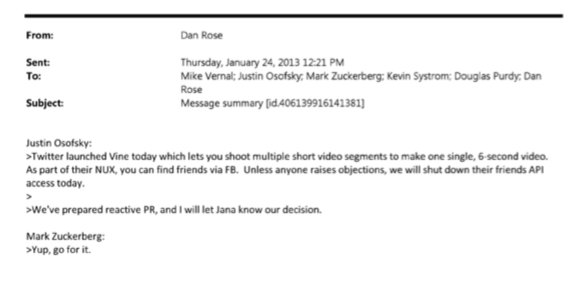

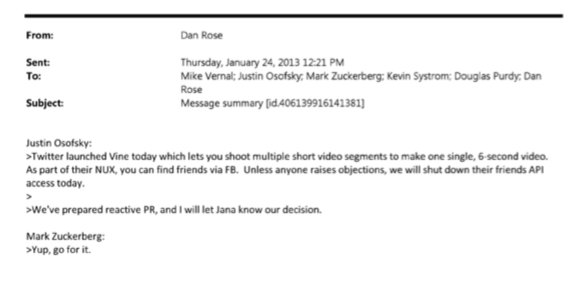

1) Zuck approves shutting down platform API access for Twitter's when Vine is released #competition

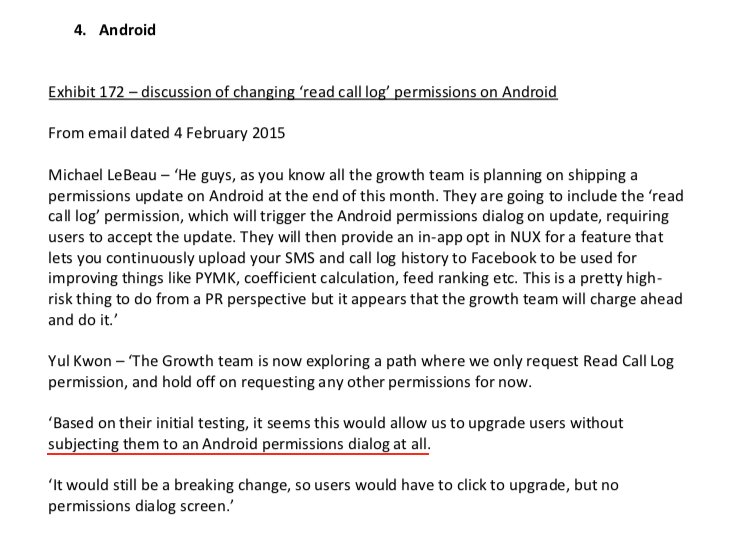

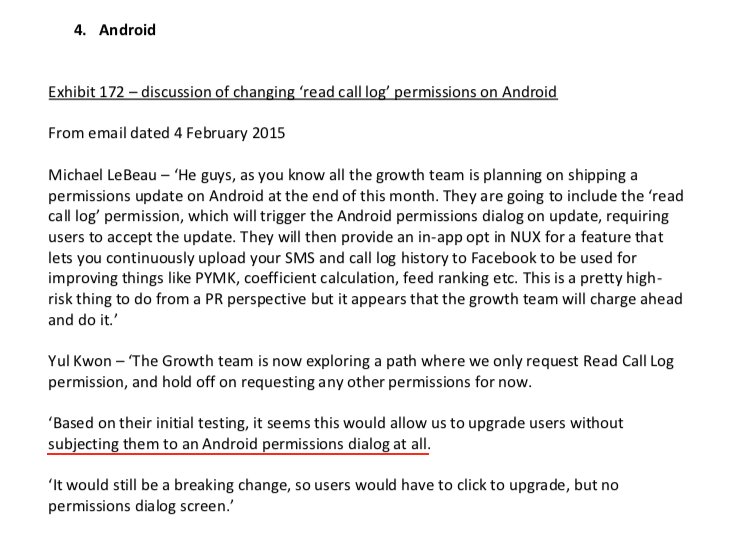

2) Facebook engineered ways to access user's call history w/o alerting users:

Team considered access to call history considered 'high PR risk' but 'growth team will charge ahead'. @Facebook created upgrade path to access data w/o subjecting users to Android permissions dialogue.

3) The above also confirms @kashhill and other's suspicion that call history was used to improve PYMK (People You May Know) suggestions and newsfeed rankings.

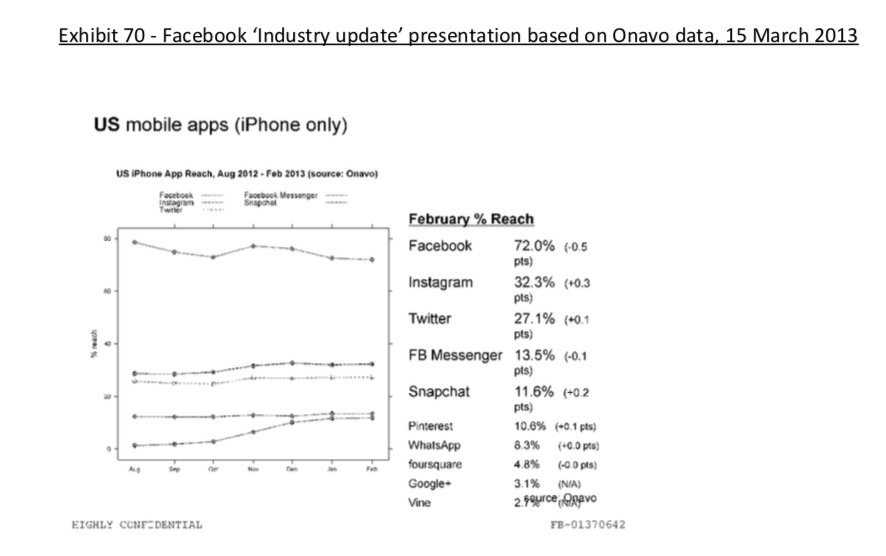

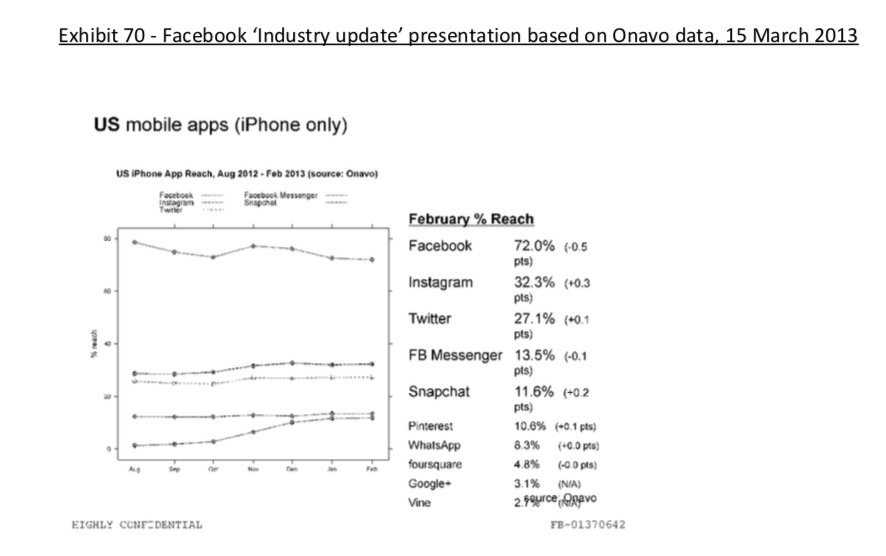

4) Docs also shed more light into @dseetharaman's story on @Facebook monitoring users' @Onavo VPN activity to determine what competitors to mimic or acquire in 2013.

https://t.co/PwiRIL3v9x

Some random interesting tidbits:

1) Zuck approves shutting down platform API access for Twitter's when Vine is released #competition

2) Facebook engineered ways to access user's call history w/o alerting users:

Team considered access to call history considered 'high PR risk' but 'growth team will charge ahead'. @Facebook created upgrade path to access data w/o subjecting users to Android permissions dialogue.

3) The above also confirms @kashhill and other's suspicion that call history was used to improve PYMK (People You May Know) suggestions and newsfeed rankings.

4) Docs also shed more light into @dseetharaman's story on @Facebook monitoring users' @Onavo VPN activity to determine what competitors to mimic or acquire in 2013.

https://t.co/PwiRIL3v9x

Joshua Hawley, Missouri's Junior Senator, is an autocrat in waiting.

His arrogance and ambition prohibit any allegiance to morality or character.

Thus far, his plan to seize the presidency has fallen into place.

An explanation in photographs.

🧵

Joshua grew up in the next town over from mine, in Lexington, Missouri. A a teenager he wrote a column for the local paper, where he perfected his political condescension.

2/

By the time he reached high-school, however, he attended an elite private high-school 60 miles away in Kansas City.

This is a piece of his history he works to erase as he builds up his counterfeit image as a rural farm boy from a small town who grew up farming.

3/

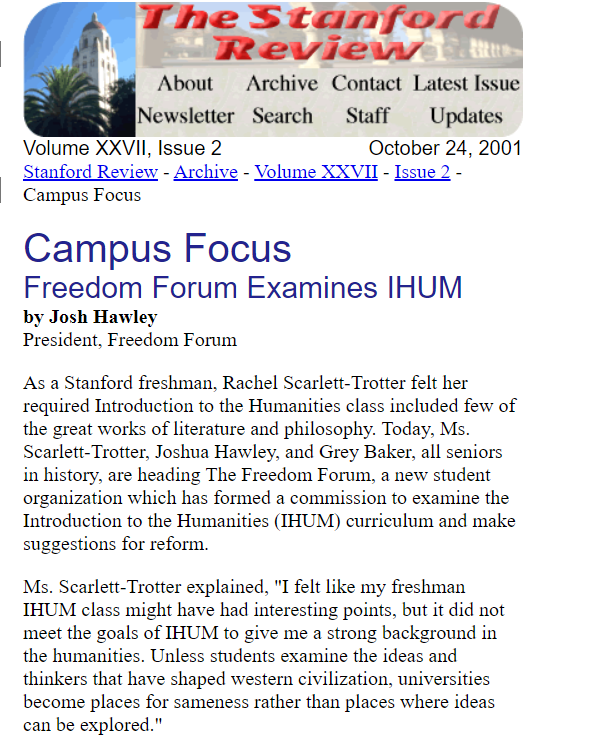

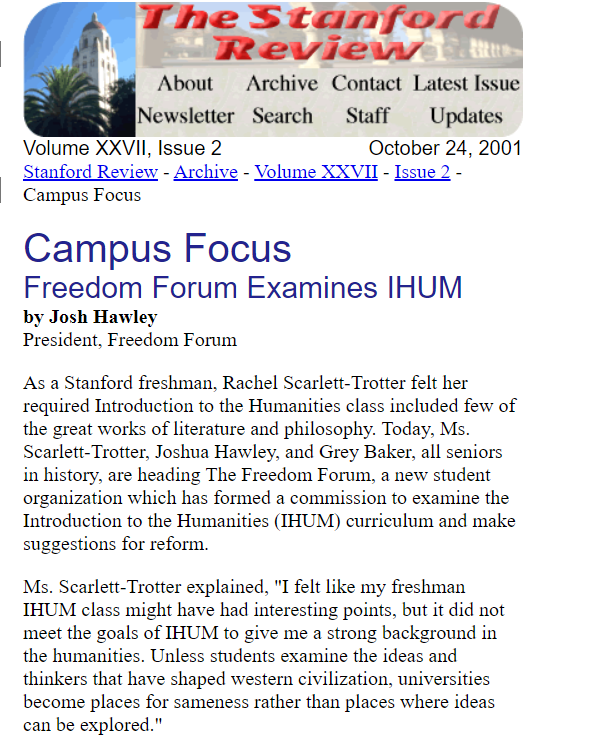

After graduating from Rockhurst High School, he attended Stanford University where he wrote for the Stanford Review--a libertarian publication founded by Peter Thiel..

4/

(Full Link: https://t.co/zixs1HazLk)

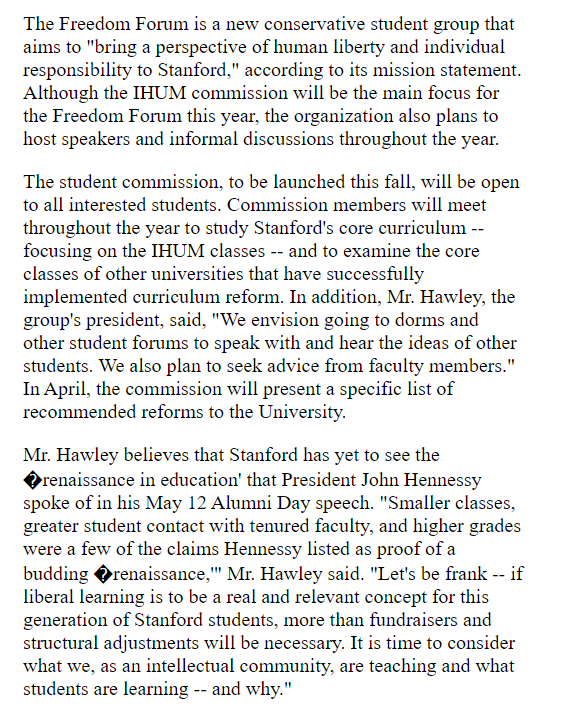

Hawley's writing during his early 20s reveals that he wished for the curriculum at Stanford and other "liberal institutions" to change and to incorporate more conservative moral values.

This led him to create the "Freedom Forum."

5/

His arrogance and ambition prohibit any allegiance to morality or character.

Thus far, his plan to seize the presidency has fallen into place.

An explanation in photographs.

🧵

Joshua grew up in the next town over from mine, in Lexington, Missouri. A a teenager he wrote a column for the local paper, where he perfected his political condescension.

2/

By the time he reached high-school, however, he attended an elite private high-school 60 miles away in Kansas City.

This is a piece of his history he works to erase as he builds up his counterfeit image as a rural farm boy from a small town who grew up farming.

3/

After graduating from Rockhurst High School, he attended Stanford University where he wrote for the Stanford Review--a libertarian publication founded by Peter Thiel..

4/

(Full Link: https://t.co/zixs1HazLk)

Hawley's writing during his early 20s reveals that he wished for the curriculum at Stanford and other "liberal institutions" to change and to incorporate more conservative moral values.

This led him to create the "Freedom Forum."

5/