Around 1900, the US was a bit of a scientific backwater when compared to Europe. Most of the exciting work was being done in Germany and Austria, especially.

Then came three enormous waves of academic and scientific talent to the US.

1) First came a group of Jewish scientists fleeing persecution.

In a massive own-goal, 1930s Nazi Germany dismissed ~15% of the physicists who made up a stunning 64% (!) of their physics citations.

The group who fleed to the US included intellectual superstars like Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard, John von Neumann, and Edward Teller who formed the backbone of the Manhattan Project.

In a pithy quote, Churchill’s military secretary Sir Ian Jacob is said to have remarked that the Allies won “because our German scientists were better than their German scientists.”

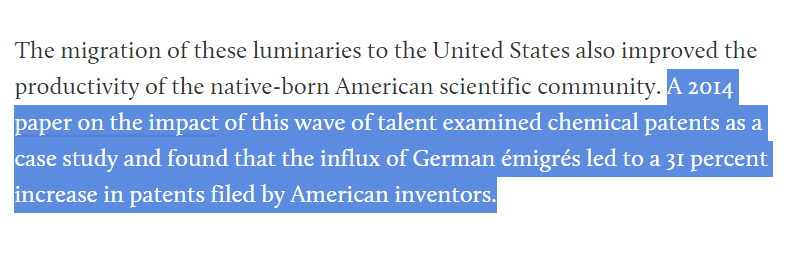

And this wasn't just a 1:1 transfer of talent, this new intellectual community pushed our domestic fields to become more productive and drew in new inventors.

2) After WWII there was a scramble between the US and the USSR for the remaining German scientists.

With the Cold War looming, the US brought over ~1,600 scientists through Operation Paperclip and the Soviets ~2,500 through Operation Osoaviakhim.

While the Americans brought fewer experts, they may have reached the brightest individuals. Included in the group was Wernher von Braun, who became the chief architect of the Saturn V rocket, and Adolf Busemann, who pioneered the concept of swept wings in aeronautics.

So the Manhattan and the Apollo projects, arguably the two greatest US techno-engineering feats of the 20th century, were the result of international scientific talent embedded in American scientific institutions.

3) A third wave of international talent recruitment could be identified in the waning years of the Cold War, as Soviet mathematicians and other academics began to look for an escape hatch.

American universities suddenly had their pick of top Soviet scientists and were bidding against each other for the brightest stars.

https://t.co/O2vKx2zpTF

There was even a policy proposal at the time to subsidize employers of these scientists, in the hope that we could assimilate all this newly available global talent as rapidly as possible.

https://t.co/i0QMZeQaEa

The net effect of these three waves has been America’s consistent domination of international science and technology.

Using the Nobel Prize in Physics as a rough proxy, American scientists were involved in only three of the thirty prizes awarded between 1901 to 1933.

From 1934 to 2020, Americans have been involved in roughly two thirds!

And a huge share of these Nobel laureates have been either first- or second-generation immigrants from these three waves.

For a period after the fall of the Soviet Union, the US was effectively able to rest on its laurels.

We were unquestionably the best location for scientific research and so most inventors/promising academics wanted to come here.

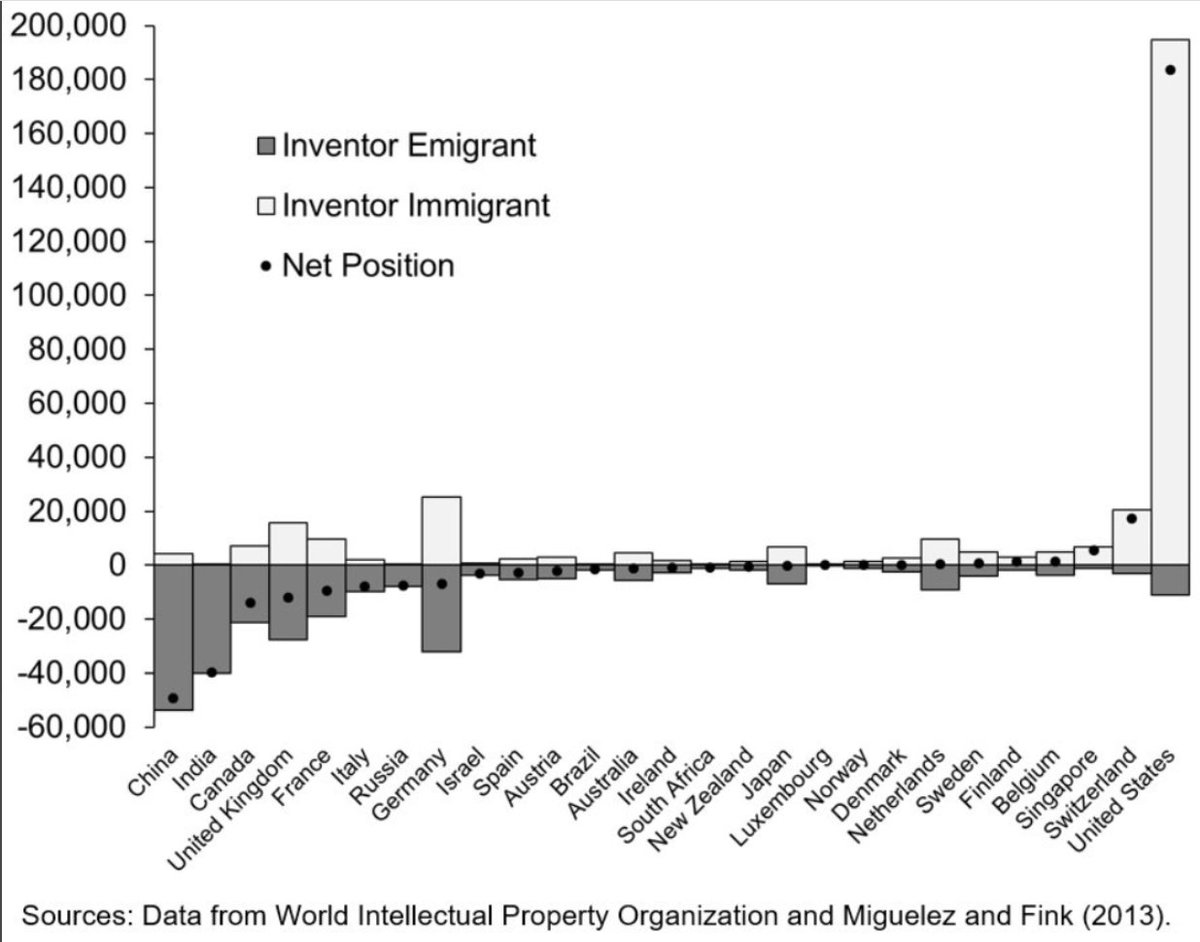

The results were stunning! Look at this chart of immigrant inventors from 2000 - 2010 from

@william_r_kerr.

But that's been starting to change. A combination of three things:

1) US immigration restrictions are growing more burdensome

2) There are better opportunities to contribute to cutting-edge research at home

3) Other countries are starting to grow more *proactive* in their attempts to poach international talent

https://t.co/EYSUhofYeO

There's a lot more we could be doing! Obviously, our immigration system is a big barrier...

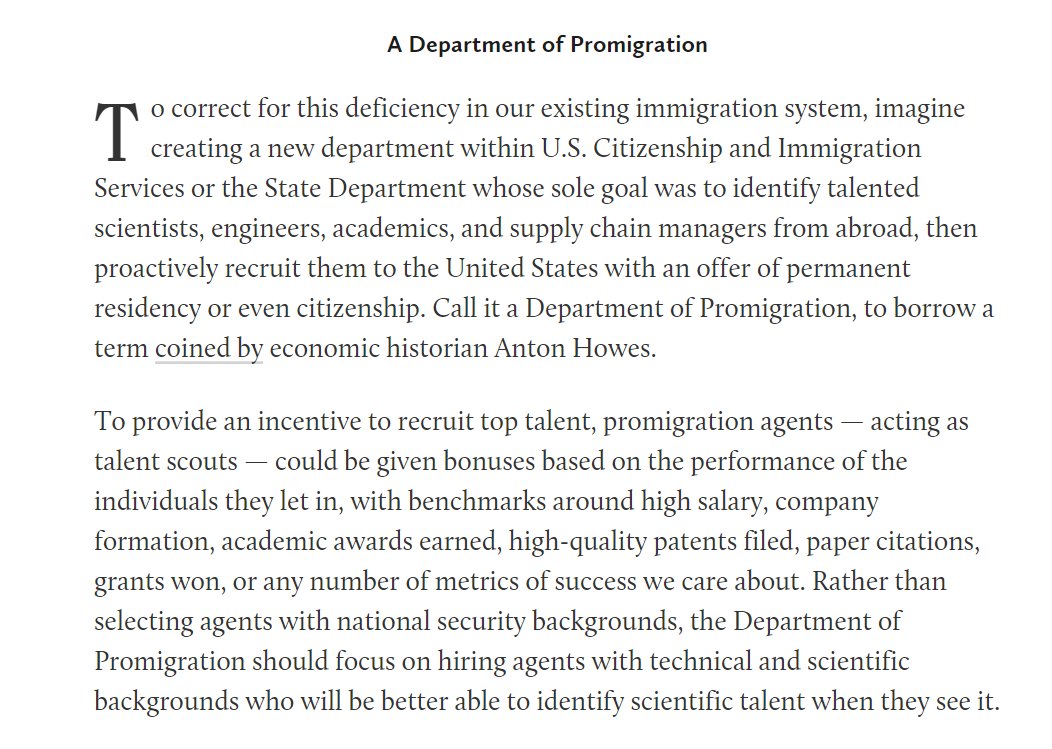

But we should go beyond these reactive measures and take a more proactive approach to talent immigration.

Today we grudgingly let the most talented individuals apply to live here; we do not actively recruit them.

Today it is concerns about identifying and stopping threats that dominates the day-to-day work of DHS.

The main job of immigration agents seems to be “avoid letting in terrorists” rather than “maximize the growth potential of the United States.”

To correct for this, I suggest we need a new department/office that has the sole mandate of finding and recruiting the most talented inventors and scientists from around the world and inviting them to live in the US.

The strength of the US has always come from being the melting pot for the world's greatest scientists and technical practitioners.

We are the R&D lab for the world and we should act like it.

Lots more on these topics and related ones in the full piece, I hope you'll check it out:

https://t.co/jwGI6exill