Some preliminary thoughts and questions about policing. All thoughts welcome, but especially thoughts from professional police officers, criminologists, sociologists, and people who've studied policing around the world:

That said: The violence also represents other, broader failings.

More from Society

You May Also Like

I hate when I learn something new (to me) & stunning about the Jeff Epstein network (h/t MoodyKnowsNada.)

Where to begin?

So our new Secretary of State Anthony Blinken's stepfather, Samuel Pisar, was "longtime lawyer and confidant of...Robert Maxwell," Ghislaine Maxwell's Dad.

"Pisar was one of the last people to speak to Maxwell, by phone, probably an hour before the chairman of Mirror Group Newspapers fell off his luxury yacht the Lady Ghislaine on 5 November, 1991." https://t.co/DAEgchNyTP

OK, so that's just a coincidence. Moving on, Anthony Blinken "attended the prestigious Dalton School in New York City"...wait, what? https://t.co/DnE6AvHmJg

Dalton School...Dalton School...rings a

Oh that's right.

The dad of the U.S. Attorney General under both George W. Bush & Donald Trump, William Barr, was headmaster of the Dalton School.

Donald Barr was also quite a

I'm not going to even mention that Blinken's stepdad Sam Pisar's name was in Epstein's "black book."

Lots of names in that book. I mean, for example, Cuomo, Trump, Clinton, Prince Andrew, Bill Cosby, Woody Allen - all in that book, and their reputations are spotless.

Where to begin?

So our new Secretary of State Anthony Blinken's stepfather, Samuel Pisar, was "longtime lawyer and confidant of...Robert Maxwell," Ghislaine Maxwell's Dad.

"Pisar was one of the last people to speak to Maxwell, by phone, probably an hour before the chairman of Mirror Group Newspapers fell off his luxury yacht the Lady Ghislaine on 5 November, 1991." https://t.co/DAEgchNyTP

OK, so that's just a coincidence. Moving on, Anthony Blinken "attended the prestigious Dalton School in New York City"...wait, what? https://t.co/DnE6AvHmJg

Dalton School...Dalton School...rings a

Oh that's right.

The dad of the U.S. Attorney General under both George W. Bush & Donald Trump, William Barr, was headmaster of the Dalton School.

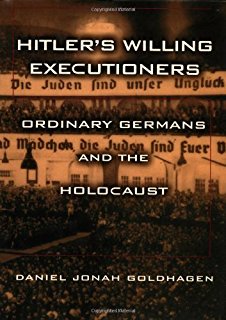

Donald Barr was also quite a

Donald Barr had a way with words. pic.twitter.com/JdRBwXPhJn

— Rudy Havenstein, listening to Nas all day. (@RudyHavenstein) September 17, 2020

I'm not going to even mention that Blinken's stepdad Sam Pisar's name was in Epstein's "black book."

Lots of names in that book. I mean, for example, Cuomo, Trump, Clinton, Prince Andrew, Bill Cosby, Woody Allen - all in that book, and their reputations are spotless.

I think a plausible explanation is that whatever Corbyn says or does, his critics will denounce - no matter how much hypocrisy it necessitates.

Corbyn opposes the exploitation of foreign sweatshop-workers - Labour MPs complain he's like Nigel

He speaks up in defence of migrants - Labour MPs whinge that he's not listening to the public's very real concerns about immigration:

He's wrong to prioritise Labour Party members over the public:

He's wrong to prioritise the public over Labour Party

One of the oddest features of the Labour tax row is how raising allowances, which the media allowed the LDs to describe as progressive (in spite of evidence to contrary) through the coalition years, is now seen by everyone as very right wing

— Tom Clark (@prospect_clark) November 2, 2018

Corbyn opposes the exploitation of foreign sweatshop-workers - Labour MPs complain he's like Nigel

He speaks up in defence of migrants - Labour MPs whinge that he's not listening to the public's very real concerns about immigration:

He's wrong to prioritise Labour Party members over the public:

He's wrong to prioritise the public over Labour Party