Obviously members of opposing parties have always worked and passed things together when interests align. But when did collaboration become not only an actual policy goal in itself but a virtue worthy of extolling?

Consider this 1960 article from historian Henry Graff in the NYT on the incoming Kennedy admin. “In domestic matters, bipartisanship is, naturally, impossible and undesirable. Although some legislation will...enjoy bipartisan support, our politics remain by nature partisan.”

“Naturally!” And Graff evidently wasn’t alone. An earlier article that year from one Douglass Cater suggested ominously that divided government after the 1960 election would be not only undesirable for domestic policymaking, but a national security risk.

If you think these were fringe ideas, here’s a '68 NYT editorial on Nixon's election. “Except in time of war...history suggests that self conscious bipartisanship does not work very well in this country…a peacetime coalition could only serve to blur the lines of responsibility"

This, clearly, is not where most folks are today. So what happened? How did we get from that to a place where, for instance, a package to address an epochal crisis that might pass by simple majority is being held up explicitly for bipartisanship’s sake?

https://t.co/ahymU0Q9Lq

Again, there are people who can speak to the complexities here much better than I can. But a story about how Bipartisanship™ came to be that I’ve found compelling — one Graff actually sketches out in his article — begins with the end of WWI and the Treaty of Versailles.

As you might know, the United States never ratified the Treaty of Versailles or joined the League of Nations due to an impasse between Wilson and Republicans in the Senate, led by Henry Cabot Lodge, who’d just won a slim majority in the 1918 midterm elections.

The actual ins and outs of what happened are a little more complicated than that and there were ideological and ethnic splits within the two parties on the matter, but that, anyway, was the story American foreign policy minds took with them into the aftermath of WWII.

One of them was Michigan Sen. Arthur Vandenberg. In 1945, he delivered a famous Senate speech repudiating his former isolationism and urging America to take an assertive role in shaping the post-war order — a goal that would require speaking with one voice on foreign policy.

As chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Vandenberg would go on to play a key role in garnering support from both sides of the aisle for the Marshall Plan and NATO. He’s generally recognized as one of the giants in the chamber’s history.

Later in 1945, FDR would appeal to the same principle Vandenburg had in a speech to Congress on Yalta and the forthcoming San Francisco conference. “The American Delegation is—in every sense of the word—bipartisan...I think that Republicans want peace just as much as Democrats.”

That was the first use of the word in the familiar sense I could find in the archives of UCSB’s American Presidency Project. Positive uses before then connote impartiality — to argue a board or commission with members from both parties was going to act on a technocratic basis.

Here’s FDR in 1932 on the U.S. Tariff Commission for instance.

But it was also used critically — here’s Hoover, for instance, arguing in 1932 that the bipartisan composition of the U.S. Shipping Board had contributed to its “lack of cohesion.”

FDR’s use in '45, in a call to set politics aside for a high purpose, is different. It also shows up in an exchange b/w Vandenberg & Eleanor Roosevelt. “Whatever our representation is in these international contacts, I...emphatically agree with you that it should be bi-partisan."

The word bipartisan had been in use since 1891 according to Merriam-Webster, but a look at Google Ngram suggests it didn’t really take off until roughly around this time — the mid to late 1940s.

Even by 1951, the word was still rare enough in political discourse that John Foster Dulles, soon to be Secretary of State, called it “new-fangled” in an address about the Treaty of San Francisco re-establishing peacetime relations with Japan.

And in a 1960 piece for the Washington Post, Truman used the word to draw a contrast between post-war diplomacy and the failure of the Treaty of Versailles—“an historic example of what could happen when a President...fails to avail himself of bipartisan Congressional support”

This is the context Bipartisanship™ as a value emerges in. It's a reference to a doctrine of cooperation specifically on foreign policy — the idea, in Vandenburg’s famous words, that politics should stop “at the water’s edge.” So how did it make the jump to domestic policy?

One early document of the broadening of the idea is this 1947 article in the Washington Post: “Bipartisanship Spreads on Hill.”

It begins with an strange suggestion made by former presidential candidate Al Landon: “An earnest recommendation to the Republican Party was made…that the Republican controlled Congress cooperate with the Democratic president in bipartisan action to deal with high prices"

The Post’s Mark Sullivan then writes that the idea, discussed "informally...outside politics" had been taken from foreign policy. “The idea is that bipartisanship has been achieved in foreign relations...and that in the domestic field, the same bipartisanship should be aimed at”

Again, cooperation between partisans on domestic policy issues wasn’t new at all. What’s being noted as novel here is the concept of bipartisanship as a value that should guide domestic policymaking rather than the unremarkable product of interests just happening to align.

And in fact, one of the things that made the idea odd in 1947 is that, as Sullivan notes, cooperation between members of both parties on domestic policy was actually quite common “So far as there is opposition between the two parties...it is a kind of token opposition”

As others have written about in recent years, a number of political scientists and others at the time actually saw the lack of partisanship within our political system as a problem.

In 1950, a report written for the American Political Science Association called “Toward a More Responsible Two-Party System” argued that the parties should become more nationalized and ideologically divided in order to produce “consistent action based on meaningful programs.”

And part of the argument here, if you can believe it, is that too much moderation and agreement between the two parties would *increase* political extremism by frustrating voters looking for more meaningful change.

The report never caught on and the parties would stay heterogenous and cooperative for some time. But bipartisanship as a virtue in domestic policy was still an anomalous concept.

It would remain so until the 1960s. And one major domestic issue where the concept began to get deliberately invoked was civil rights.

By the early 60s, a consensus had formed that the fight over civil rights had become a national crisis. This was reflected in editorials like this 1963 one from the Washington Post lauding “gestures on Capitol Hill towards bipartisan cooperation” in advancing civil rights bills.

And this particular editorial offers an illuminating quote from then Senator Hubert Humphrey. Race relations, Humphrey said, had risen to such importance, that the situation had come to demand “the same kind of bipartisanship we have on foreign affairs.”

Of course, the clear divides on civil rights in 1963 were really within the parties — and within the Democratic Party in particular — rather than between them, as the editorial notes. And, again, coalitions between members of both parties were common on other issues.

But civil rights, obviously, had not been like other issues. Civil rights were an “explosive issue.” And here, coalition building had to be induced by a call for a higher sort of politics rather than “politics-as-usual.”

Here’s the New York Times editorial board echoing Humphrey a week later. “Just as bipartisanship has characterized the Congressional response to international crises, so it must bring unity in this great domestic crisis.”

But you also begin to see around this time the word coming to refer generically to proposals that members of both parties had come to agree on.

Johnson in particular really went to town with it. Transportation? A bipartisan problem. This bill on controlling nuclear material? Bipartisan. The Higher Education Act? Bipartisan. This park? Bipartisan.

But as much as Johnson talked up bipartisanship, Democrats had huge majorities in the House and Senate during his term and the programs and initiatives of the Great Society were built largely upon them. And this perhaps accounts for the cynicism you hear in that ‘68 editorial.

And this is critical: from the turn of the century through the end of the 1960s, one party government was the norm. As you see in that Cater piece from 1960, divided government under Ike had been unusual enough that the idea of it continuing was cause for concern in some circles.

But divided government was the future. Civil rights and cultural issues broke up the New Deal coalition and scrambled American politics. Nixon and Ford preside over Democratic congresses. There’s a return to unified control under Carter. It’s rare afterwards.

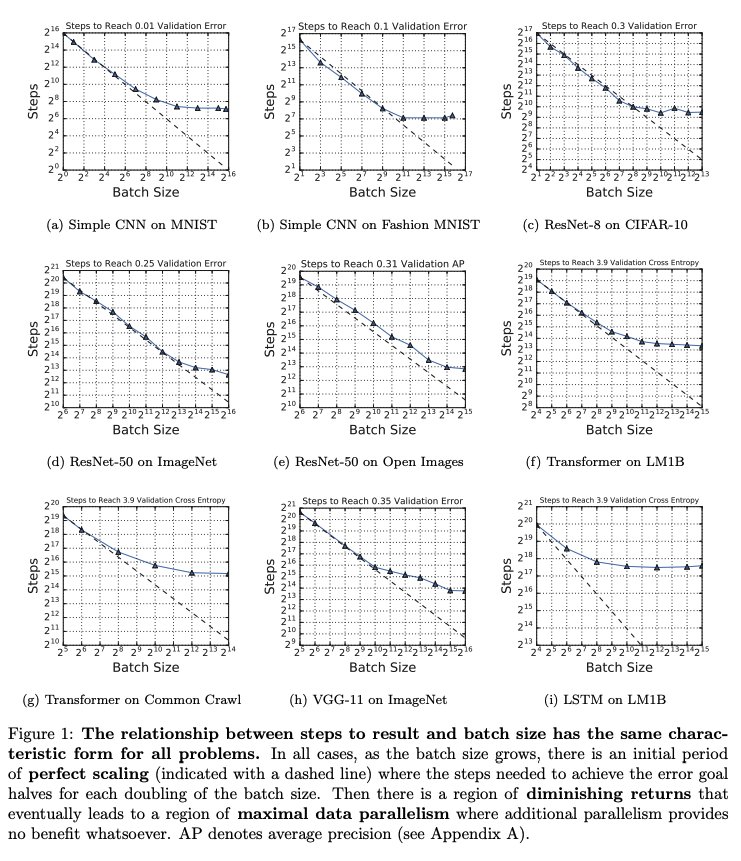

Look at that Ngram again. The use of bipartisan shoots up from the late 1970s and peaks in the late 1990s. The parties are becoming more ideologically sorted in this period, but these are also the years of what we now call the neoliberal consensus.

In short, the Republican Party moves right and the Democratic Party moves with it to recapture voters they had begun losing to the conservative movement.

For Dems, that meant trying to outflank Reagan on issues like the deficit. Here’s a laudatory 1986 piece from the Philadelphia Inquirer on the the Democratic Leadership Council and their call for Reagan “ to join them in a bipartisan anti-deficit drive.”

We know most of the story from here, really. The Democrats take the center. They return to power under Clinton in '92. Republicans sweep Congress in '94. The period produces bipartisan policies we’re still trying to dig ourselves out of today. David Broder on Biden’s crime bill:

Here's a cameo from John Kasich, then a congressman from Ohio, who tells Broder that Clinton would have to learn from the example to work with Republicans once they made gains in the midterms.

This is ultimately what happened. Here’s Clinton outlining his priorities in 1996’s State of the Union. Deficits and welfare reform had been on the Democratic agenda, but Republicans played a larger role in shaping policy after gaining majorities.

A last look at that NGram. Usage of “bipartisanship” seems to fall off a cliff in the late 90s, but obviously not because politicians stop using it.

I’d guess this is probably polarization at work. It appears less frequently in increasingly partisan books and media even as (or maybe even because) it’s common in the rhetoric of actual elected officials.

A final thought: the salience of bipartisanship as a value is *the product* of political division. The concept only makes sense as a normative principle if there’s a deep gulf between two sides, each with its own coherent identity.

Bipartisanship™ doesn’t really exist in a world where there’s substantial overlap between the two parties and agreement is common. Because then, that’s just politics. You don’t need a special name for that state of affairs. And for a long time they didn’t have one.

That 1947 article again: “Without being formally aimed at, bipartisanship informally exists as respects the two parties in Congress. Without having made agreement about it, without indeed being much conscious of it, the two parties practice it.”

In short, the trajectory of bipartisanship as an idea particularly after the late 1970s seems to track roughly with the deepening of political polarization. Put another way: bipartisanship takes off as a value as *and in fact because* agreement becomes less and less possible.

And to the extent that you do see significant bipartisan policies enacted, the policies are largely center-right to conservative. It’s obvious whose interests they serve.

So here’s where we are. 4,000 coronavirus deaths a day. A full package of policies to address the crisis might pass with a simple partisan majority via reconciliation. Evidently this won't happen. Why? Because the president is “bipartisan-curious.”

https://t.co/ahymU0Q9Lq

This is how deeply the concept has burrowed into our politics. It is taken entirely for granted by many Americans that this is how things have to work. It is not. The premise is rarely challenged explicitly, even by elected progressives. It should be.