It takes 5 justices to hear this case, rather than the usual 4.

I'm still seeing a lot of concern about the Texas Supreme Court filing, which is understandable. From a certain angle, it looks imposing.

So here, in sum, is why there's no need for alarm (thread):

It takes 5 justices to hear this case, rather than the usual 4.

The TX case is something else entirely and could have been heard in lower courts (many have rejected similar claims).

First, The Constitution specifically gives each state the right to run its elections as it sees fit. Done and done.

The Court won't countenance that.

More from Law

A Warning:

The 'Freeports' in at least 10 locations in Britain will evolve into Charter Cities with their own laws. They will NOT be legally bound to ANY of the trade agreements between the UK and EU or any other country. They will be used to bypass all International scrutiny

'Sovereign UK' makes deal with Charter city (physically but NOT legally part of the UK) which then trades to other countries OUTSIDE of the constraints of International laws

Thus bypassing all restrictions , tariff, tax, human rights, climate change legislation - everything

https://t.co/f35zFvkCHQ

The 'Freeports' in at least 10 locations in Britain will evolve into Charter Cities with their own laws. They will NOT be legally bound to ANY of the trade agreements between the UK and EU or any other country. They will be used to bypass all International scrutiny

'Sovereign UK' makes deal with Charter city (physically but NOT legally part of the UK) which then trades to other countries OUTSIDE of the constraints of International laws

Thus bypassing all restrictions , tariff, tax, human rights, climate change legislation - everything

https://t.co/f35zFvkCHQ

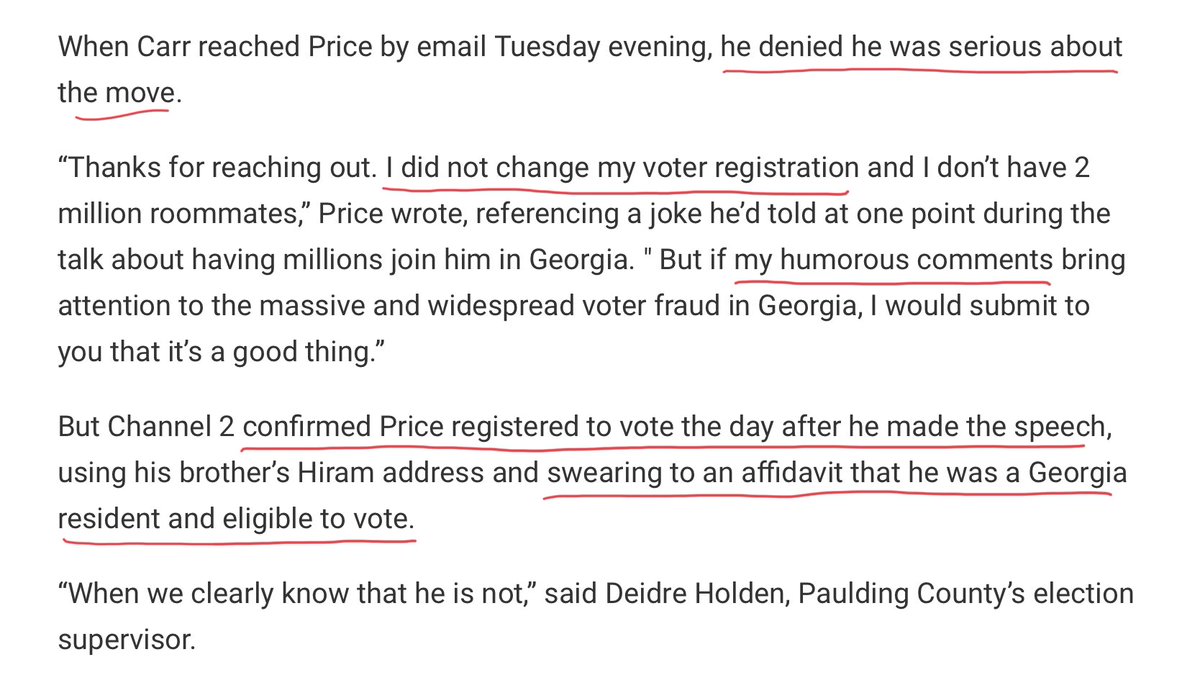

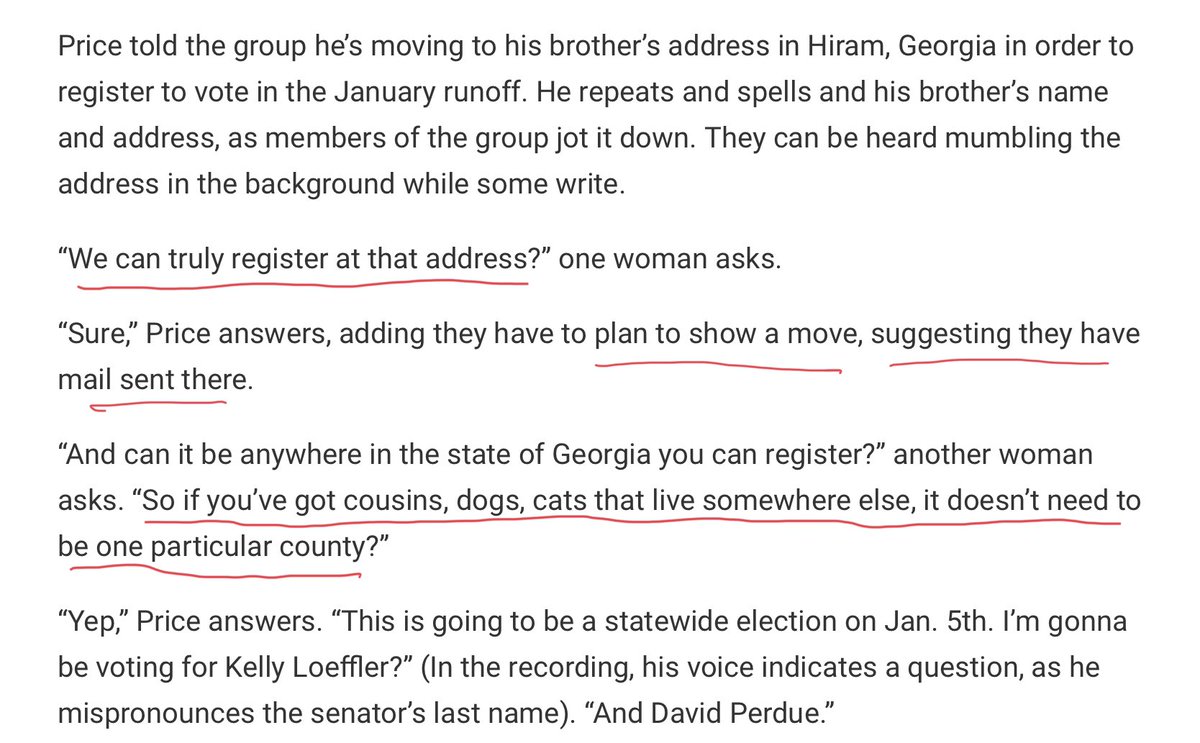

Holy Shit. Florida GOPer caught on tape telling fellow FL GOPers to make false voter registrations in Georgia so they could vote to save Loeffler and Perdue. He in fact DID register in Georgia and is now under investigation.

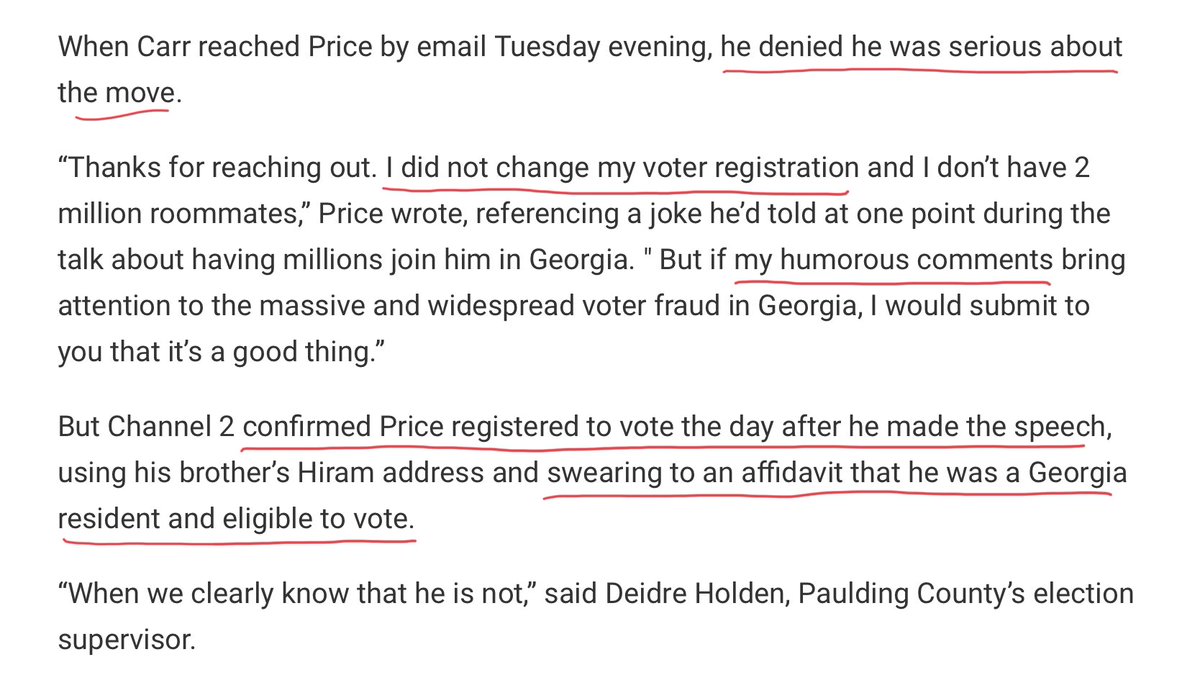

2/ A pretty kickass reporter, Nicole Carr, recorded the video before the guy took it down. When she confronted him he insisted it was all a joke and of course he didn’t register in Georgia. But she checked and he had.

3/ This is Nicole Carr ...

4/ amazing. Here’s where she catches him 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤔🤔

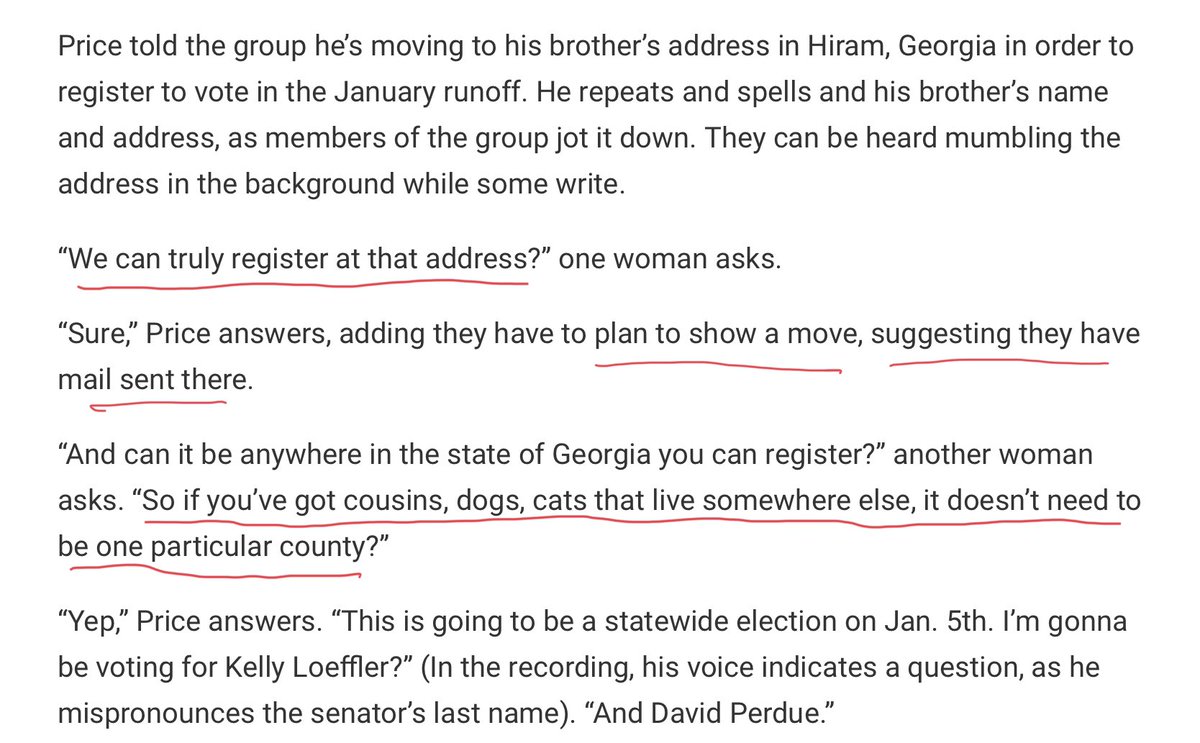

5/ Also on the video you’ve got these ladies saying, hey wait, this can’t really be legal can it? And he’s like, yeah totally cool. Then he advises on how to create a backstory for the fake move.

2/ A pretty kickass reporter, Nicole Carr, recorded the video before the guy took it down. When she confronted him he insisted it was all a joke and of course he didn’t register in Georgia. But she checked and he had.

3/ This is Nicole Carr ...

\u201cIf that means changing your address for the next two months,so be it.I\u2019m doing that. I\u2019m moving to Georgia.\u201dOur 6 investigation reveals deleted video-a FL attorney telling GOP members how to move to GA,vote in runoffs. It\u2019s illegal.There\u2019s more,& an investigation @wsbtv #gapol pic.twitter.com/or2PgWQrT1

— Nicole Carr (@NicoleCarrWSB) December 2, 2020

4/ amazing. Here’s where she catches him 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤔🤔

5/ Also on the video you’ve got these ladies saying, hey wait, this can’t really be legal can it? And he’s like, yeah totally cool. Then he advises on how to create a backstory for the fake move.

You May Also Like

1/ Here’s a list of conversational frameworks I’ve picked up that have been helpful.

Please add your own.

2/ The Magic Question: "What would need to be true for you

3/ On evaluating where someone’s head is at regarding a topic they are being wishy-washy about or delaying.

“Gun to the head—what would you decide now?”

“Fast forward 6 months after your sabbatical--how would you decide: what criteria is most important to you?”

4/ Other Q’s re: decisions:

“Putting aside a list of pros/cons, what’s the *one* reason you’re doing this?” “Why is that the most important reason?”

“What’s end-game here?”

“What does success look like in a world where you pick that path?”

5/ When listening, after empathizing, and wanting to help them make their own decisions without imposing your world view:

“What would the best version of yourself do”?

Please add your own.

2/ The Magic Question: "What would need to be true for you

1/\u201cWhat would need to be true for you to\u2026.X\u201d

— Erik Torenberg (@eriktorenberg) December 4, 2018

Why is this the most powerful question you can ask when attempting to reach an agreement with another human being or organization?

A thread, co-written by @deanmbrody: https://t.co/Yo6jHbSit9

3/ On evaluating where someone’s head is at regarding a topic they are being wishy-washy about or delaying.

“Gun to the head—what would you decide now?”

“Fast forward 6 months after your sabbatical--how would you decide: what criteria is most important to you?”

4/ Other Q’s re: decisions:

“Putting aside a list of pros/cons, what’s the *one* reason you’re doing this?” “Why is that the most important reason?”

“What’s end-game here?”

“What does success look like in a world where you pick that path?”

5/ When listening, after empathizing, and wanting to help them make their own decisions without imposing your world view:

“What would the best version of yourself do”?