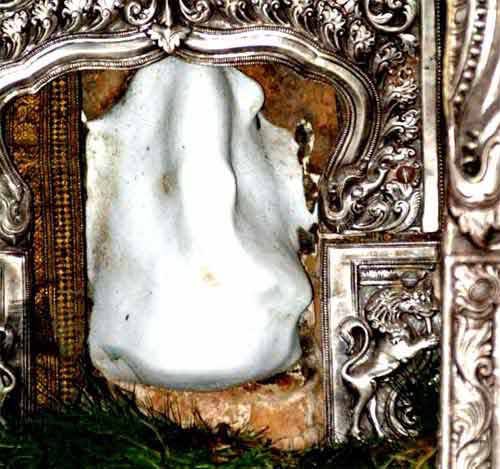

"The prospective buyer responded and explained that their absolute maximum amount they can spend is $100,000 USD. They are accountants and explained this is an extraordinary amount of money for them." /2

I sympathize with mid-size companies seeking to acquire a premium domain name. Even if they stretch to make the maximum possible offer, it often still can't compete with what a larger company can offer. Their desired domain name remains always out of reach. /1

"The prospective buyer responded and explained that their absolute maximum amount they can spend is $100,000 USD. They are accountants and explained this is an extraordinary amount of money for them." /2