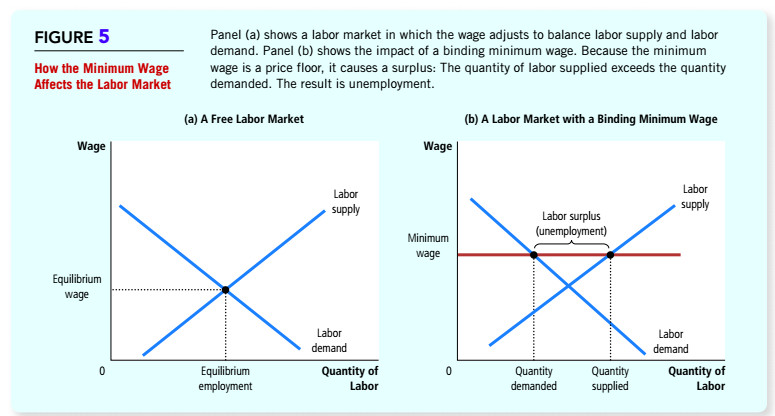

1/ To add a little texture to @NickHanauer's thread, it's important to recognize that there's a good reason why orthodox economists (& economic cosplayers) so vehemently oppose a $15 min wage:

The min wage is a wedge that threatens to undermine all of orthodox economic theory.

1/4 Most people, especially academic economists, think that the controversy over the minimum wage is a contest over facts. It's not. It's a contest over power, status, and wealth. It is just like the contest over racial and gender justice.

— Nick Hanauer (@NickHanauer) January 17, 2021

https://t.co/SjPUBEzedr

https://t.co/5VQ70XuX5Q

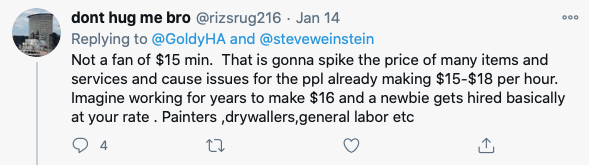

e.g. tweets like this:

Thought experiment: imagine you've spent years working your way up to $15/hour...

a) Continue to earn $15 while the newbies get $7.25? or

b) Get a bump up $16 while the newbies earn $15?

The orthodox behavioral model says b) every time! It's just not in your self-interest to turn down an extra $1/hour. That's $2,080 a year!

Fortunately, that example is just a hypothetical.

More from Economy

You May Also Like

Great article from @AsheSchow. I lived thru the 'Satanic Panic' of the 1980's/early 1990's asking myself "Has eveyrbody lost their GODDAMN MINDS?!"

The 3 big things that made the 1980's/early 1990's surreal for me.

1) Satanic Panic - satanism in the day cares ahhhh!

2) "Repressed memory" syndrome

3) Facilitated Communication [FC]

All 3 led to massive abuse.

"Therapists" -and I use the term to describe these quacks loosely - would hypnotize people & convince they they were 'reliving' past memories of Mom & Dad killing babies in Satanic rituals in the basement while they were growing up.

Other 'therapists' would badger kids until they invented stories about watching alligators eat babies dropped into a lake from a hot air balloon. Kids would deny anything happened for hours until the therapist 'broke through' and 'found' the 'truth'.

FC was a movement that started with the claim severely handicapped individuals were able to 'type' legible sentences & communicate if a 'helper' guided their hands over a keyboard.

For three years I have wanted to write an article on moral panics. I have collected anecdotes and similarities between today\u2019s moral panic and those of the past - particularly the Satanic Panic of the 80s.

— Ashe Schow (@AsheSchow) September 29, 2018

This is my finished product: https://t.co/otcM1uuUDk

The 3 big things that made the 1980's/early 1990's surreal for me.

1) Satanic Panic - satanism in the day cares ahhhh!

2) "Repressed memory" syndrome

3) Facilitated Communication [FC]

All 3 led to massive abuse.

"Therapists" -and I use the term to describe these quacks loosely - would hypnotize people & convince they they were 'reliving' past memories of Mom & Dad killing babies in Satanic rituals in the basement while they were growing up.

Other 'therapists' would badger kids until they invented stories about watching alligators eat babies dropped into a lake from a hot air balloon. Kids would deny anything happened for hours until the therapist 'broke through' and 'found' the 'truth'.

FC was a movement that started with the claim severely handicapped individuals were able to 'type' legible sentences & communicate if a 'helper' guided their hands over a keyboard.