But the essay itself commits that sin. We can't observe *something*--problems in medicine--without expanding it to *everything*; & we can't observe *anything* without saying we can "fix it."

1/36 A thread on Alana Newhouse's Tablet essay. I'm sorry to criticize an essay framed around a writer's ill child.

But my dream for the 2020s is to read big, serious essays whose premises aren't "everything is broken," & that don't say "how to fix

But the essay itself commits that sin. We can't observe *something*--problems in medicine--without expanding it to *everything*; & we can't observe *anything* without saying we can "fix it."

I looked inside.

The cover was an ad, and the "thing" that changed everything turned out to be a Dolce & Gabbana-branded Smeg toaster.

This is a really bad problem, though, not just the minor price of admission to public life.

I say "philosophy, not "tactic," b/c if we use it enough, it becomes a mindset.

Is it different to claim “everything is broken” than it is to say “the world fell apart under Obama"?

This is a privileged fantasy.

Some SA friends gave me side-eye. They would move to the US.

"They don't look like they're suffering like my family is suffering," one said bluntly.

But then she backtracks--or forward-tracks and traces the bad things to the Obama administration.

Institutions on which we could depend?

I remember academia touting Communism for seven decades, and the NYT stating in 1954 that Ho Chi Minh was "over."

Honestly, this sounds like a description of the academy and the NYT 1946-2000 to me.

The US economic system retreats to being the elephant in the room.

Mandated by whom? Amazon is no less of a “cultural vehicle” than HBO.

There's a reason economics is avoided after halfway--investigating it would upend the advice.

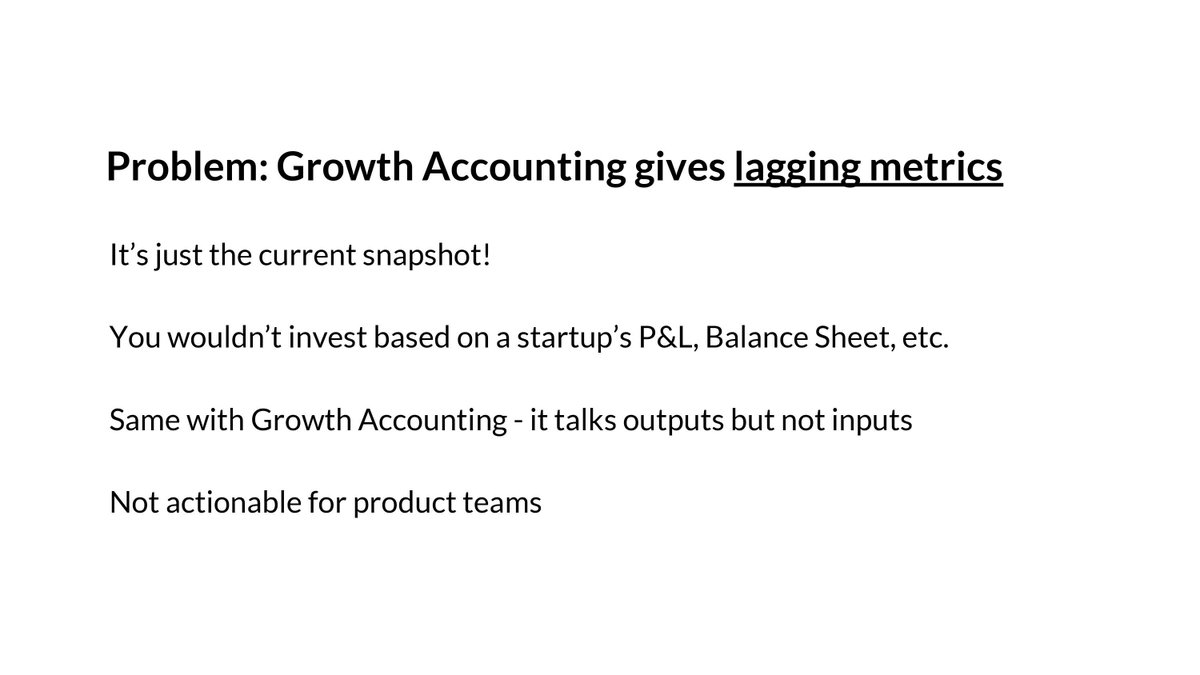

Unless you're really careful and do an exceptional job, you have to erect a false world to describe "everything" about it in a few thousand words.

It's the known way to cut through noise. Most of my editors now title my articles "The Key to X" or "Everything Is Y." The more hyperbolic, alarmist, or sweeping magazine articles get, the better they do, financially--and they're struggling.

More from Culture

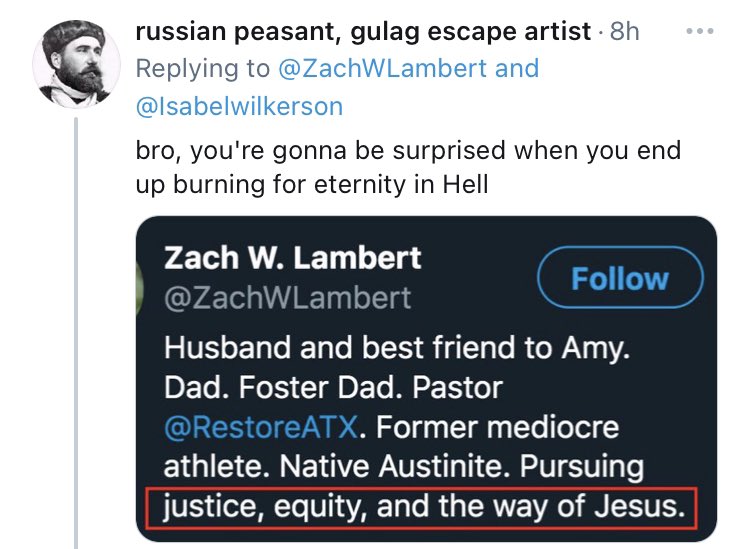

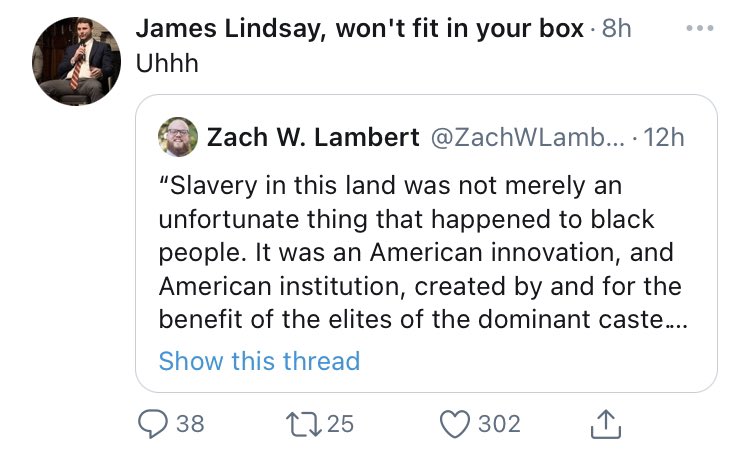

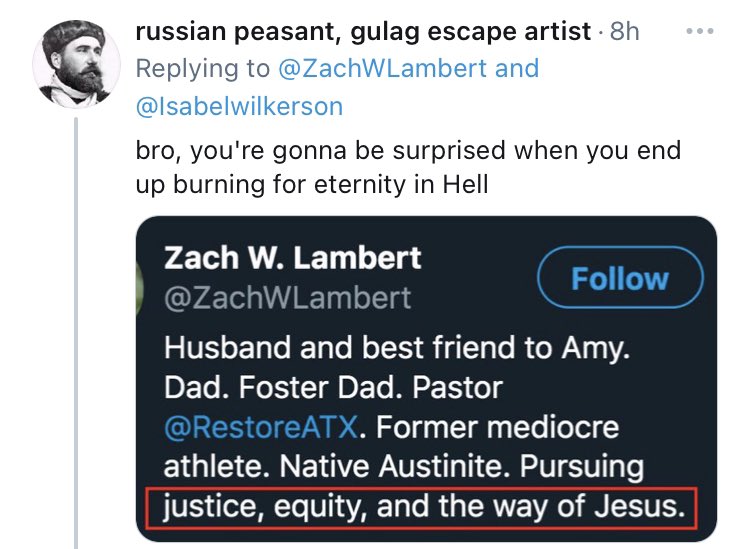

I woke up this morning to hundreds of notifications from this tweet, which is literally just a quote from a book I am giving away tonight.

The level of vitriol in the replies is a new experience for me on here. I love Twitter, but this is the dark side of it.

Thread...

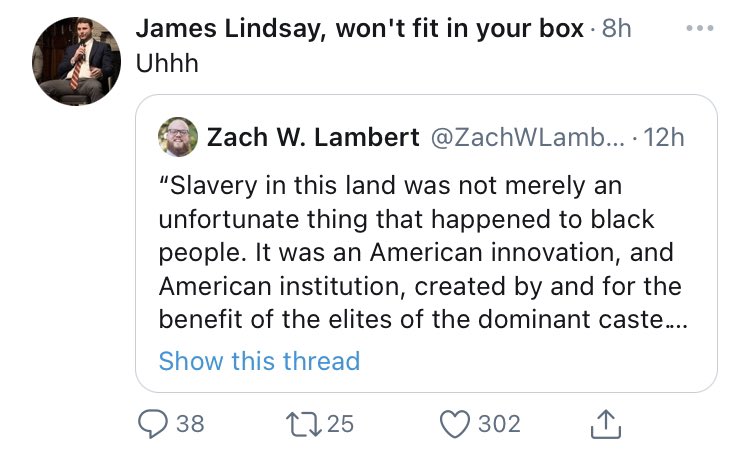

First, this quote is from a book which examines castes and slavery throughout history. Obviously Wilkerson isn’t claiming slavery was invented by America.

She says, “Slavery IN THIS LAND...” wasn’t happenstance. American chattel slavery was purposefully crafted and carried out.

That’s not a “hot take” or a fringe opinion. It’s a fact with which any reputable historian or scholar agrees.

Second, this is a perfect example of how nefarious folks operate here on Twitter...

J*mes Linds*y, P*ter Bogh*ssian and others like them purposefully misrepresent something (or just outright ignore what it actually says as they do in this case) and then feed it to their large, angry following so they will attack.

The attacks are rarely about ideas or beliefs, because purposefully misrepresenting someone’s argument prevents that from happening. Instead, the attacks are directed at the person.

The level of vitriol in the replies is a new experience for me on here. I love Twitter, but this is the dark side of it.

Thread...

\u201cSlavery in this land was not merely an unfortunate thing that happened to black people. It was an American innovation, and American institution, created by and for the benefit of the elites of the dominant caste.\u201d @Isabelwilkerson

— Zach W. Lambert (@ZachWLambert) February 11, 2021

First, this quote is from a book which examines castes and slavery throughout history. Obviously Wilkerson isn’t claiming slavery was invented by America.

She says, “Slavery IN THIS LAND...” wasn’t happenstance. American chattel slavery was purposefully crafted and carried out.

That’s not a “hot take” or a fringe opinion. It’s a fact with which any reputable historian or scholar agrees.

Second, this is a perfect example of how nefarious folks operate here on Twitter...

J*mes Linds*y, P*ter Bogh*ssian and others like them purposefully misrepresent something (or just outright ignore what it actually says as they do in this case) and then feed it to their large, angry following so they will attack.

The attacks are rarely about ideas or beliefs, because purposefully misrepresenting someone’s argument prevents that from happening. Instead, the attacks are directed at the person.