2/n

Fellow academics, when are we going to start fixing our urgent structural problems that strain family bonds and present ongoing barriers to diversifying our educational and scientific leadership? You wonder, what the heck is this guy talking about?

1/n

2/n

3/n

Teaching: 20h/w x 20w = 400h

Meetings of all sorts: 10h/w x 48w= 480h

Replying to email: 2h/d x 365d = 730h

Attending and giving talks: 2h/w x 50w = 100h

4/n

5/n

6/n

7/n

8/n

9/n

10/n

11/n

12/n

13/n

14/n

15/n

16/n

17/n

18/n

https://t.co/cMbIIRmlwi

19/n

20/n

21/n

22/n

23/n

More from Science

Hard agree. And if this is useful, let me share something that often gets omitted (not by @kakape).

Variants always emerge, & are not good or bad, but expected. The challenge is figuring out which variants are bad, and that can't be done with sequence alone.

You can't just look at a sequence and say, "Aha! A mutation in spike. This must be more transmissible or can evade antibody neutralization." Sure, we can use computational models to try and predict the functional consequence of a given mutation, but models are often wrong.

The virus acquires mutations randomly every time it replicates. Many mutations don't change the virus at all. Others may change it in a way that have no consequences for human transmission or disease. But you can't tell just looking at sequence alone.

In order to determine the functional impact of a mutation, you need to actually do experiments. You can look at some effects in cell culture, but to address questions relating to transmission or disease, you have to use animal models.

The reason people were concerned initially about B.1.1.7 is because of epidemiological evidence showing that it rapidly became dominant in one area. More rapidly that could be explained unless it had some kind of advantage that allowed it to outcompete other circulating variants.

Variants always emerge, & are not good or bad, but expected. The challenge is figuring out which variants are bad, and that can't be done with sequence alone.

Feels like the next thing we're going to need is a ranking system for how concerning "variants of concern\u201d actually are.

— Kai Kupferschmidt (@kakape) January 15, 2021

A lot of constellations of mutations are concerning, but people are lumping together variants with vastly different levels of evidence that we need to worry.

You can't just look at a sequence and say, "Aha! A mutation in spike. This must be more transmissible or can evade antibody neutralization." Sure, we can use computational models to try and predict the functional consequence of a given mutation, but models are often wrong.

The virus acquires mutations randomly every time it replicates. Many mutations don't change the virus at all. Others may change it in a way that have no consequences for human transmission or disease. But you can't tell just looking at sequence alone.

In order to determine the functional impact of a mutation, you need to actually do experiments. You can look at some effects in cell culture, but to address questions relating to transmission or disease, you have to use animal models.

The reason people were concerned initially about B.1.1.7 is because of epidemiological evidence showing that it rapidly became dominant in one area. More rapidly that could be explained unless it had some kind of advantage that allowed it to outcompete other circulating variants.

Ever since @JesseJenkins and colleagues work on a zero carbon US and this work by @DrChrisClack and colleagues on incorporating DER, I've been having the following set of thoughts about how to reduce the risk of failure in a US clean energy buildout. Bottom line is much more DER.

Typically, when we see zero-carbon electricity coupled to electrification of transport and buildings, implicitly standing behind that is totally unprecedented buildout of the transmission system. The team from Princeton's modeling work has this in spades for example.

But that, more even than the new generation required, runs straight into a thicket/woodchipper of environmental laws and public objections that currently (and for the last 50y) limit new transmission in the US. We built most transmission prior to the advent of environmental law.

So what these studies are really (implicitly) saying is that NEPA, CEQA, ESA, §404 permitting, eminent domain law, etc, - and the public and democratic objections that drive them - will have to change in order to accommodate the necessary transmission buildout.

I live in a D supermajority state that has, for at least the last 20 years, been in the midst of a housing crisis that creates punishing impacts for people's lives in the here-and-now and is arguably mostly caused by the same issues that create the transmission bottlenecks.

Rooftop solar can play a key role in a transition to 100% renewable energy - and it can help American's pocketbooks #GoSolarhttps://t.co/6p9jb62EGW

— Environment America (@EnvAm) January 14, 2021

Typically, when we see zero-carbon electricity coupled to electrification of transport and buildings, implicitly standing behind that is totally unprecedented buildout of the transmission system. The team from Princeton's modeling work has this in spades for example.

But that, more even than the new generation required, runs straight into a thicket/woodchipper of environmental laws and public objections that currently (and for the last 50y) limit new transmission in the US. We built most transmission prior to the advent of environmental law.

So what these studies are really (implicitly) saying is that NEPA, CEQA, ESA, §404 permitting, eminent domain law, etc, - and the public and democratic objections that drive them - will have to change in order to accommodate the necessary transmission buildout.

I live in a D supermajority state that has, for at least the last 20 years, been in the midst of a housing crisis that creates punishing impacts for people's lives in the here-and-now and is arguably mostly caused by the same issues that create the transmission bottlenecks.

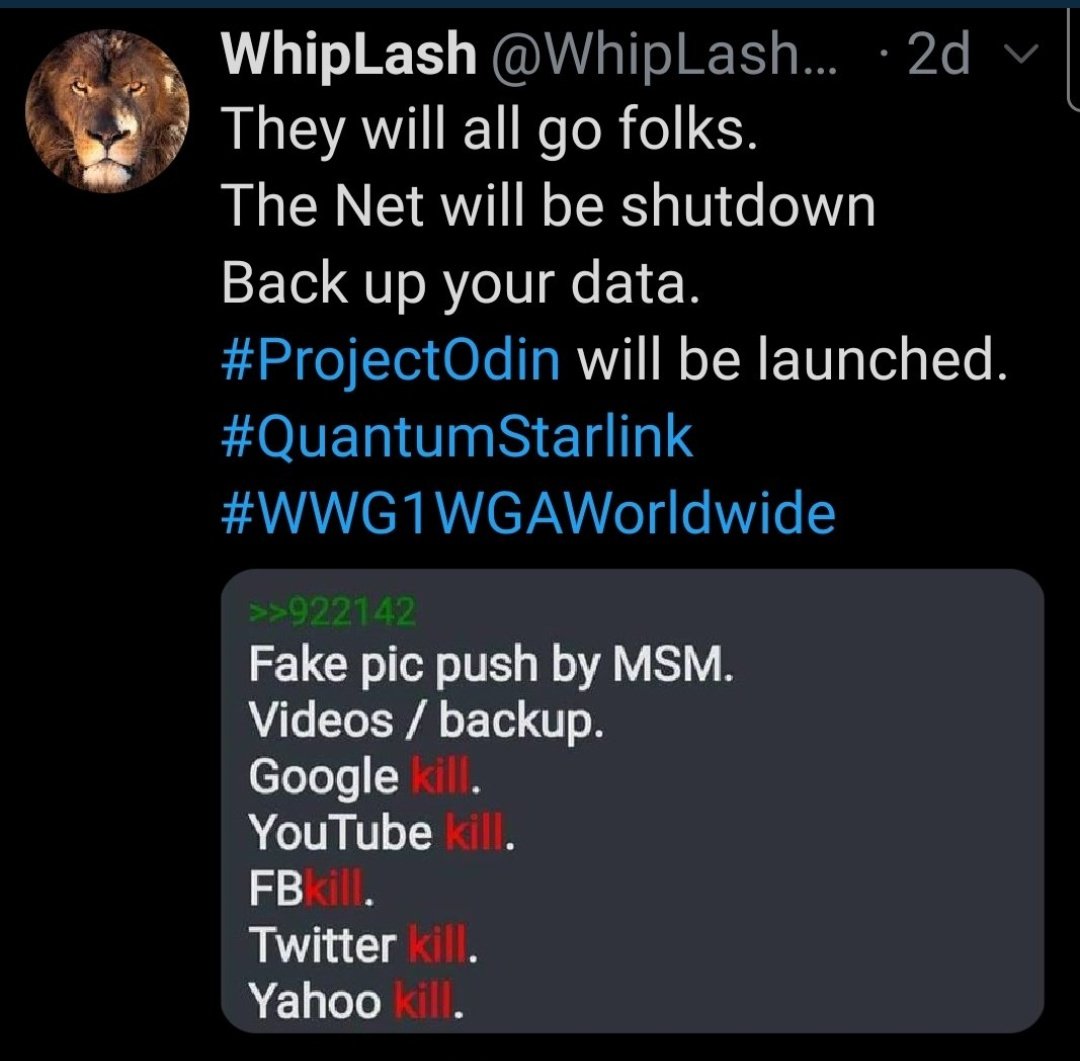

💥and so it begins..💥

It's time, my friends 🤩🤩

[Thread] #ProjectOdin

https://t.co/fO90N78fta

new quantum-based internet #ElonMusk #QVS #QFS

Political justification ⏬⏬

#ProjectOdin

#ProjectOdin #Starlink #ElonMusk #QuantumInternet

It's time, my friends 🤩🤩

[Thread] #ProjectOdin

The Alliance has Project Odin ready to go - the new quantum-based internet. #ElonMusk #QVS #QFS #ProjectOdin

— Der Preu\xdfe Parler: @DerPreusse (@DerPreusse1963) January 12, 2021

https://t.co/fO90N78fta

new quantum-based internet #ElonMusk #QVS #QFS

Political justification ⏬⏬

#ProjectOdin

#ProjectOdin #Starlink #ElonMusk #QuantumInternet