A few thoughts on tax policy. Thread:

So you are worth >$100M or perhaps even a few billion. There are only two ways to become this rich.

1. You start a business that becomes very successful.

2. You inherit wealth from your family. 1/

More from Economy

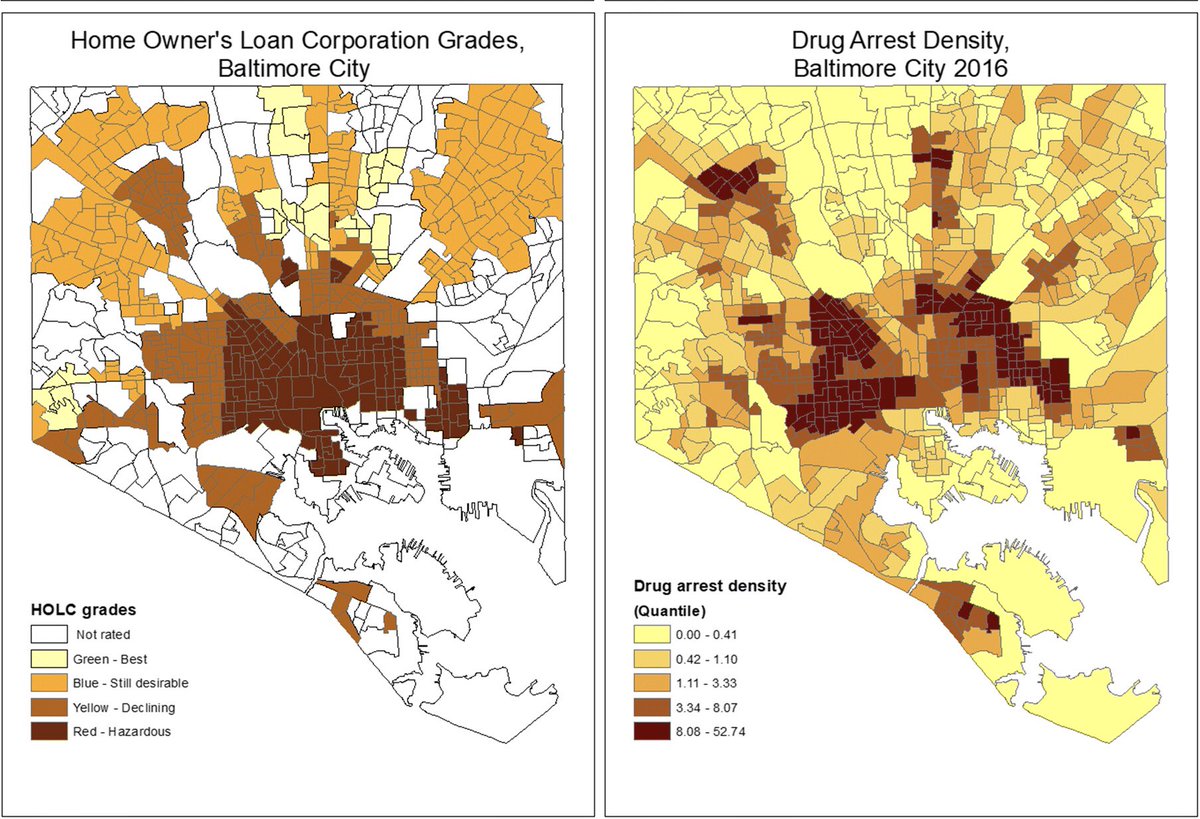

I know I’ve been beating this redlining and wealth gap drum for 20+ years but here is a GREAT cliffs notes version.

But don’t take @ambermruffin’s word for it. You should get references...

A thread

How homes in Black neighborhoods are undervalued by $156

Every major bank in the US has been sued for mortgage discrimination and a study that included every mortgage in America found that Banks charge higher interest rates to nonblack customers

https://t.co/sx9tWWB98s

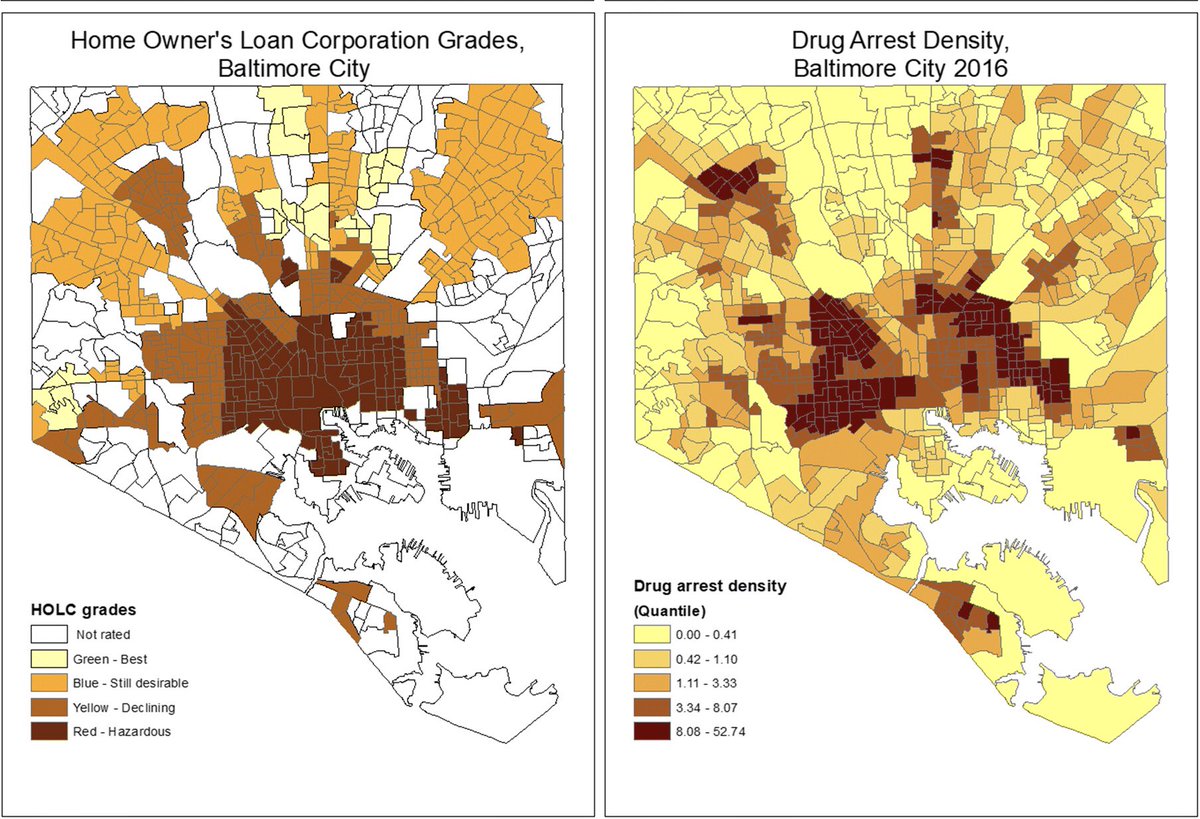

Baltimore redlined areas in 1935 vs Baltimore Drug arrests in 2016

But don’t take @ambermruffin’s word for it. You should get references...

A thread

How did systemic racism get so dang strong? Find out a few of the like bajilliondy ways in our new segment, How Did We Get Here! pic.twitter.com/f4HfISckXh

— amber ruffin (@ambermruffin) January 30, 2021

How homes in Black neighborhoods are undervalued by $156

Every major bank in the US has been sued for mortgage discrimination and a study that included every mortgage in America found that Banks charge higher interest rates to nonblack customers

https://t.co/sx9tWWB98s

Baltimore redlined areas in 1935 vs Baltimore Drug arrests in 2016