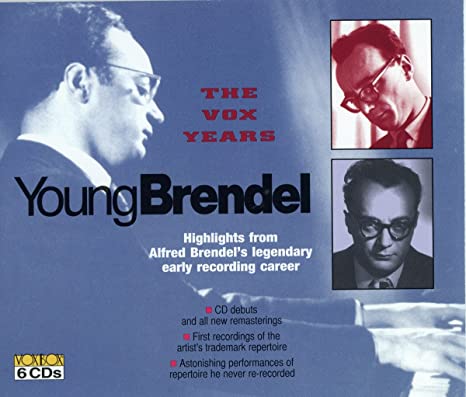

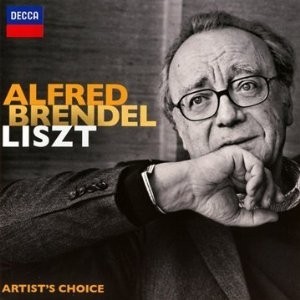

"Music, Sense and Nonsense: Collected Essays and Lectures", por Alfred Brendel.

Capítulo: “Conversations - Talking to Brendel with Jeremy

More from Music

Open Question to fellow investors tracking Music Industry.

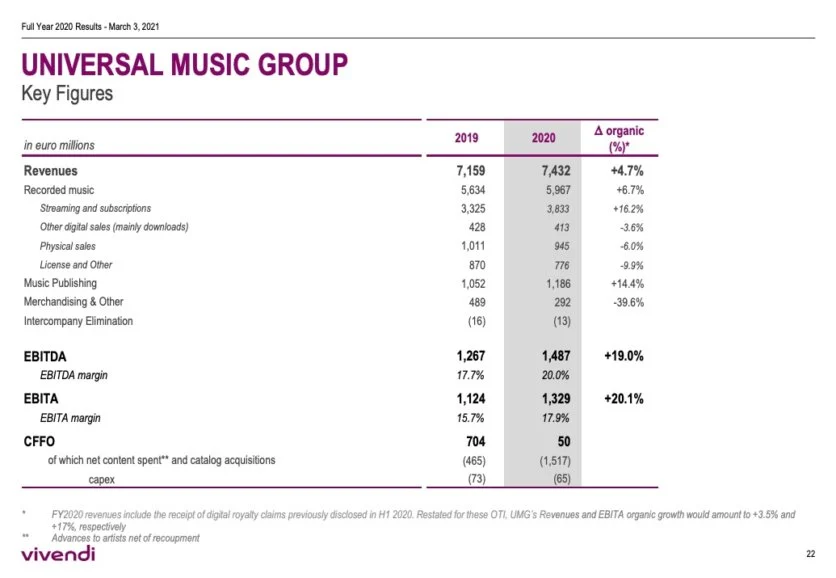

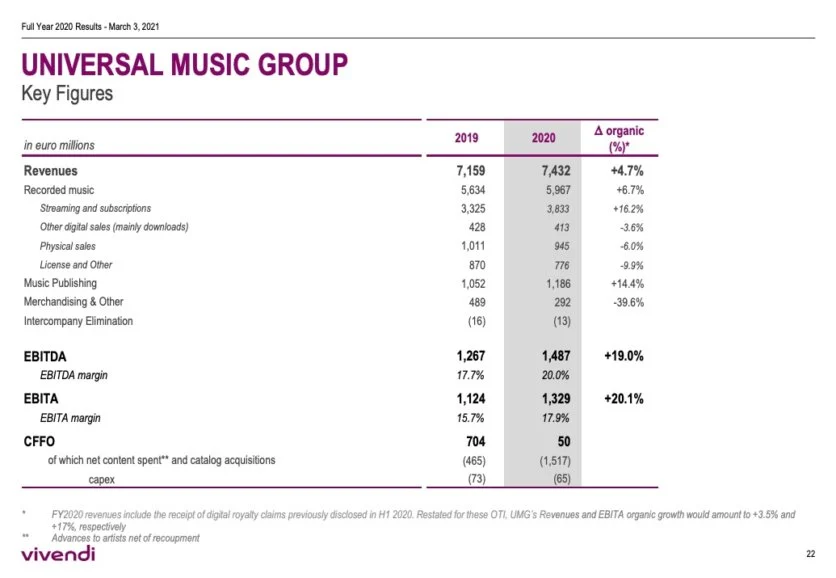

A business like Universal which controls more than 1/3rd of all published music globally is selling for less than 6x FY20 Sales.

Why are Indian businesses like Saregama / Tips selling for 11x, 20x their sales?

If I include all of the revenue generated by entire firm, its selling for ~4.5x FY20 Sales

Universal Listing Market Cap ~ 40 Billion USD

FY 20 Revenues ~ 8.87 B USD or 7.4B EUR

Catalogue of Music includes every international artist you can possibly name

Either Universal is grossly undervalued or Saregama/Tips are grossly overvalued.

https://t.co/aHzWSYtcUt

https://t.co/v0EMoCuYKX

A business like Universal which controls more than 1/3rd of all published music globally is selling for less than 6x FY20 Sales.

Why are Indian businesses like Saregama / Tips selling for 11x, 20x their sales?

If I include all of the revenue generated by entire firm, its selling for ~4.5x FY20 Sales

Universal Listing Market Cap ~ 40 Billion USD

FY 20 Revenues ~ 8.87 B USD or 7.4B EUR

Catalogue of Music includes every international artist you can possibly name

Either Universal is grossly undervalued or Saregama/Tips are grossly overvalued.

https://t.co/aHzWSYtcUt

Homework for all the interested participants here:

— Intrinsic Compounding (@soicfinance) June 27, 2021

Q1.Why 20% and not 50%+ Margins for UMG

Q2. Differences in dynamics between Western&Indian cos?

Q3. Trends in West vs Trends in India in the industry.

Research and find the answers. My job is done \U0001f601\U0001f64f

https://t.co/v0EMoCuYKX

If you see the ebitda of universal music its low 20% compared to our saregama 30% or tips 50%. So when you compare earnings saregama is 40x and tips is 30x and universal music is 30x. Also these type of companies are less( low or no capex with excellent and growinh cashflows)

— Srikanth V (@mynameisnani75) June 27, 2021

You May Also Like

Joshua Hawley, Missouri's Junior Senator, is an autocrat in waiting.

His arrogance and ambition prohibit any allegiance to morality or character.

Thus far, his plan to seize the presidency has fallen into place.

An explanation in photographs.

🧵

Joshua grew up in the next town over from mine, in Lexington, Missouri. A a teenager he wrote a column for the local paper, where he perfected his political condescension.

2/

By the time he reached high-school, however, he attended an elite private high-school 60 miles away in Kansas City.

This is a piece of his history he works to erase as he builds up his counterfeit image as a rural farm boy from a small town who grew up farming.

3/

After graduating from Rockhurst High School, he attended Stanford University where he wrote for the Stanford Review--a libertarian publication founded by Peter Thiel..

4/

(Full Link: https://t.co/zixs1HazLk)

Hawley's writing during his early 20s reveals that he wished for the curriculum at Stanford and other "liberal institutions" to change and to incorporate more conservative moral values.

This led him to create the "Freedom Forum."

5/

His arrogance and ambition prohibit any allegiance to morality or character.

Thus far, his plan to seize the presidency has fallen into place.

An explanation in photographs.

🧵

Joshua grew up in the next town over from mine, in Lexington, Missouri. A a teenager he wrote a column for the local paper, where he perfected his political condescension.

2/

By the time he reached high-school, however, he attended an elite private high-school 60 miles away in Kansas City.

This is a piece of his history he works to erase as he builds up his counterfeit image as a rural farm boy from a small town who grew up farming.

3/

After graduating from Rockhurst High School, he attended Stanford University where he wrote for the Stanford Review--a libertarian publication founded by Peter Thiel..

4/

(Full Link: https://t.co/zixs1HazLk)

Hawley's writing during his early 20s reveals that he wished for the curriculum at Stanford and other "liberal institutions" to change and to incorporate more conservative moral values.

This led him to create the "Freedom Forum."

5/

Recently, the @CNIL issued a decision regarding the GDPR compliance of an unknown French adtech company named "Vectaury". It may seem like small fry, but the decision has potential wide-ranging impacts for Google, the IAB framework, and today's adtech. It's thread time! 👇

It's all in French, but if you're up for it you can read:

• Their blog post (lacks the most interesting details): https://t.co/PHkDcOT1hy

• Their high-level legal decision: https://t.co/hwpiEvjodt

• The full notification: https://t.co/QQB7rfynha

I've read it so you needn't!

Vectaury was collecting geolocation data in order to create profiles (eg. people who often go to this or that type of shop) so as to power ad targeting. They operate through embedded SDKs and ad bidding, making them invisible to users.

The @CNIL notes that profiling based off of geolocation presents particular risks since it reveals people's movements and habits. As risky, the processing requires consent — this will be the heart of their assessment.

Interesting point: they justify the decision in part because of how many people COULD be targeted in this way (rather than how many have — though they note that too). Because it's on a phone, and many have phones, it is considered large-scale processing no matter what.

It's all in French, but if you're up for it you can read:

• Their blog post (lacks the most interesting details): https://t.co/PHkDcOT1hy

• Their high-level legal decision: https://t.co/hwpiEvjodt

• The full notification: https://t.co/QQB7rfynha

I've read it so you needn't!

Vectaury was collecting geolocation data in order to create profiles (eg. people who often go to this or that type of shop) so as to power ad targeting. They operate through embedded SDKs and ad bidding, making them invisible to users.

The @CNIL notes that profiling based off of geolocation presents particular risks since it reveals people's movements and habits. As risky, the processing requires consent — this will be the heart of their assessment.

Interesting point: they justify the decision in part because of how many people COULD be targeted in this way (rather than how many have — though they note that too). Because it's on a phone, and many have phones, it is considered large-scale processing no matter what.